By Reinhard Zollitsch

August 2000

On ocean paddling – Boston, MA to Machias, ME

The ultimate test for ocean paddlers in our neck of the woods is the 350-mile- long Maine Island Trail from Portland to Machias. Being out on the ocean in a tiny boat is always a big deal, but going 300 miles unassisted with all your gear in the boat certainly is a step up from the usual day or weekend tripping. The nice thing about the MIT is that you can almost always dash behind an island or into a bay or bight if the going gets too rough. And if you get out with the lobstermen before sunrise you are almost always guaranteed 5 to 6 good paddling hours - and that’s already 20 - 24 miles before lunch, leaving the afternoon for exploring the shore, reading, writing, resting or just plain having fun.

Rounding points like Cape Small, Pemaquid and Schoodic, you quickly learn, are best done in the early morning before the wind springs up. And yes, you do have to watch out for the strong ebb tides out of the bigger rivers or tidal estuaries as well as across bars, especially with an opposing wind. The mouth of the Kennebec River, the Bass Harbor and Petit Manan Bars are the most notorious.

I have very nice memories of my first long ocean canoe trip loosely following the MIT in my dear old open 16’ Jensen solo whitewater racer, which I had adapted to ocean canoeing by installing a rudder, 3’ decks, extra flotation and a tie-down system. It took me 13 days that summer, averaging 23 miles per day, but it took a lot of skill and prudence to keep the ocean out of the boat.

Fundy Fog

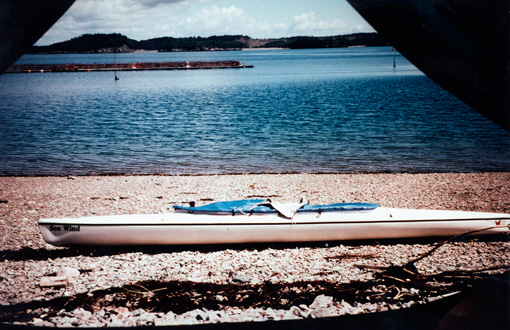

So when I decided to explore the almost 150 miles from Boston to Portland the next year, to go Down East all the way (See “Messing about in Boats”, Wenham, MA, April 1, 1998) I finally decided to get a new Verlen Kruger 17’ 2” Sea Wind sea canoe with rudder and spray skirt. This southern “extension of the MIT”, as I call it, is quite different from the Portland to Machias coastline. It is very exposed and open to the sea, has hardly any islands to hide behind or bays to run into. It has either steep rocky shores or long shoaling beaches, which whip into white froth a mile out or more.

I vividly remember poking my bow out of the Anisquam River near Gloucester into whitecaps as far as the eye could see. It was blowing 20+ from the ESE, and I thought it over long and hard, sizing up the waves, before I decided to go for it, trying to wend my way, dancing between shore break and outer big wave break. The 16 miles or 4 hours to Salisbury Beach taxed me to the max. I could not afford a single lapse of concentration, dancing with the quartering waves, outrunning the breaking part. Needless to say, I was glad I made it up the still-ebbing mouth of the Merrimack River, up through the dual breakwaters, to the beach, where I plopped out of my canoe, totally spent.

Nicer memories of that trip, but as always quite exciting, were mailing myself through the slot of the outlying ledges into Brave Boat Harbor, or riding the nape of a big cresting wave across the toothy Richmond Island bar, or bounding on the big waves around Cape Elizabeth and Portland Head. The only calm and sheltered spot along the entire 150 miles was the Cape Porpoise area. What a place, especially at low tide. And then there was Perkins Cove, right out of a van Gogh painting, wooden drawbridge and all.

Island Trail East

Having found out how it feels going Down East all the way from Boston, like in the old schooner days, my curiosity now wandered even further down east, into the Bay of Fundy to St. John, New Brunswick, another 130 miles beyond Machias, Maine. If the MIT is the baseline for sea kayaking/canoeing skills, the Boston to Portland stretch added the element of being exposed to the open ocean and surf along the shoaling beaches. Boaters need much more skill and strength for the longer commitments, since there are no easy outs.

The Bay of Fundy now adds significant tides to the equation, up to 29 feet in St. John, and still 21 feet in Eastport, ME. And where there are significant tidal differences, there are correspondingly strong tidal flows and even rips. With a cruising speed of only 4 miles per hour (max 5 MPH), I knew it would be totally futile to buck the strong tides and get nowhere. So very careful preparation, chart and tide table reading and meticulous planning are a must in these waters, especially if you solo your boat unassisted as I do. I knew I had to catch the “Fundy Bay Ebb Tide Express” to get back to Maine from St. John, NB, because that was going to be the direction of my travel.

St. John River

Since I had paddled the St. John River from the top to the last dam at Mactaquac near Fredericton, NB in previous years, I thought it would be neat to finish the river trip and use the 92 miles to the city of St. John as a warm-up and shake-down. And what a wonderful free-flowing perfectly navigable, often very wide river it was. Early settlers came up the St. John valley, mostly to establish farms in the wide, lush, marshy flood-plane of the mighty river, often referred to as the “Rhine of North America”, vying with the Hudson River for that distinction. A handful of big lakes drain into the St. John; the biggest of them is 25-mile-long and 3-mile-wide Grand Lake.

Farming is still going on along its banks and even on the flat mid-stream islands. The first night out I pitched my little Eureka tent on Middle Island near Burton, when suddenly a herd of about 50 cows and a handful of horses came over to check me out. On another island, young kids had been haying and I met them rafting tractor and hay-load across the river to their farm, where their dad was waiting to help them ashore.

The third day on the river I canoed down Long Reach towards Harding, a straight 16-mile-long and almost 2-mile-wide arm of the river, by now slightly tidal. It felt like the Maine coast, like going down Eggemoggin or Moosabec Reach. A perfect sailing area, I thought, out of the vicious ocean tides and the ubiquitous thick fog, which St. John is known for.

I got a taste of it though the next day. I had only 12 more miles to go to Reversing Falls, the infamous narrow outflow of the St. John River. I had to steer a compass course across Grande Bay to the western shore, and from there I had two more crossings to make, before I could sneak into Indian Harbor just above the Falls. I set a course right under a power line crossover. I only faintly saw the wires 25 meters (82 feet) above me on the first half-mile crossing towards Green Head at the entrance to the Narrows.

The second crossover was only a quarter mile wide, but the fog was so thick, I never saw the power line 31 meters (102 feet) overhead. I did not even see the tall masts on either side that held them up. But my compass and time/distance/speed calculations worked out and I made it fine, slipping into Indian Harbor to size up the situation.

The tide was still running out. I could hear the roar, and wanted none of it under these conditions and without careful scouting. From the harbor I cautiously inched over to the very edge of the whitewater stretch, to Prospect Point, where I pulled out and set up camp on a small patch of level ground. I felt this spot must have been used a lot in the days of river travel.

This was it for the day, only 12 miles, my lowest mileage ever, but from now on, I knew I had to go with the flow, with the proper tide that is. I considered the old Indian portage from my spot up and around the Falls, but only for a very brief moment. Portaging all my gear did not appeal to me, and I was looking forward to the challenge ahead.

Later that afternoon the fog lifted somewhat and I had a chance to look at Reversing Falls from the high bluff behind me on river left. Except for maybe 60 minutes around slack tide (officially only 10 minutes!), the whole area from my tent site to the very restricted area of the highway bridge, the water was a solid mess of breaking waves, some as tall as 8 feet. My chart points out a 5 meter bar extending across the river to the big paper mill. A very foreboding site for a small boater, fun only for the big powerful jet boats, which take tourists into this maelstrom, soaking and tossing them thoroughly.

Reversing Falls, St. John, NB - flowing upstream

For a moment I considered slipping through at slack high at 4:00 PM, but decided against it. Even though I liked the idea of catching the ebb tide on the other side of the Falls towards Lorneville, it was simply too late in the day to get there, too difficult to portage ashore at Lorneville at ebb tide, and the fog most likely was still out there or could suddenly waft in again. It was a no go situation.

At slack high, one sailboat slipped in and a small freighter steamed out. So it could be done - I liked seeing that and enjoyed my supper and reading immensely. I would catch tomorrow’s slack low at 11:55 AM, I decided, and have enough time and hopefully better weather to get to Lorneville.

Through Reversing Falls into Fundy Bay

Next morning I was 35 minutes early sizing up the last of the ebb tide. The big waves had miraculously diminished; it was still running hard, but more level. Suddenly I heard this little voice in me saying: “This is it. You can do it. Go for it!” And I did, confidently and swiftly, with a few bounces, but no face slappers towards the bridge. I had read about the big whirlpool there on the left, but all was smooth sailing.

People were standing high up on the right on a viewing platform cheering the lonesome paddler, which must have looked like a tiny white speck in the dark churning waters of the St. John. I managed a quick heli-twirl with my paddle. How frivolous, I thought, but I felt relieved to have made it through - this was my brief moment of celebration of having finished the first leg of my trip, 92 miles in 4 days.

But the real Bay of Fundy trip was only beginning.

I had read that low at Reversing Falls occurs 3:50 hours after low in the ocean. That meant that the tide was already almost two thirds in, and I would have to buck a flood tide for my first target, Lorneville, 12 miles down the coast, no easy task for the first day on the Bay.

It did not take long to realize I was back on the ocean. The water was heaving and surging, always moving. And then there always seems to be wind, and infallibly on the nose (SSW, 20+ knots). I was in for a slugfest before I knew it. I ducked under the St. John to Digby, Nova Scotia ferry dock and hugged the breakwater out to Partridge Island. At that point, tide and wind ganged up on me, and I had a hard time making it around the island. I quickly shifted into my old marathon racing mode and dug in as hard as I could, because if I didn’t, I would not go anywhere.

Ever so slowly I bounced, slammed and squirreled around the point, then got out of the strong tidal flow as fast as possible and back to shore on the other side of the breakwater. Tide and wind were in my face as I slugged along shore, just far enough out to avoid the shore break. At Duck Cove I was sorely tempted to pull out on a nice sandy beach, but I had not yet reached my goal for the day.

At Sheldon Point it was “déja vu all over again”, into the wind and against the tide - no fun. A sudden brief moment of brilliant sun made the hard paddle almost palatable, but minutes later I was again engulfed in thick fog and never really saw Saints Rest Beach and Taylor’s Island. As long as the roaring surf was on my right, I thought, I was OK.

Seeley Point across from Lorneville was the last test for today. The fog had lifted as fast as it had come, but the wind was streaming straight at me. My bow went under on every second wave, I got wet, and only with determined energy did I make it around the point. It was only about a mile from Lorneville as the crow flies, but that was totally out of the question for me. I had to go way into the next bay before I could contemplate crossing over. Even at that, I was taxed to the max and wondered what I was doing out there. I switched into the no-mistake mode and steadily and confidently ferried across the bay and then up to the breakwater of Lorneville.

Elation at getting to my goal for today, even though it was only twelve miles, was mixed with the disappointment of not finding any take-out, no beach, ramp or shore to step out on. Reluctantly I went further into the Lorneville harbor bay, which my charts told me would run dry completely at low tide. For how long, was the question. How long would the tide hold me hostage here if I pulled out now?

Riding the ebb tide express back home

I realized I did not have much of a choice. It was time to come in. The tide was up, and therefore it was easy to take out. So I quickly figured it should be high at about 4:30 AM tomorrow morning. I could get up and be out of here before the tide ran out. I can do that. I was determined to catch the “Fundy Ebb Tide Express” back towards Maine, come tomorrow morning. No more bucking the tide. Paddling against a prevailing SW wind was bad enough.

Coffee tasted good that afternoon, and Dinty Moore did himself proud serving dinner that night. A brief swim, trip log, some reading, then packing for an early start tomorrow. At sundown the entire bight was dry, as a matter of fact, it was dry as far as I could see - the ocean had vanished. Time to go to bed and not worry about tomorrow’s departure.

4:00 AM Atlantic time felt like the middle of the night. The stars were still out, so was a sliver of a moon - Orion was tipped to the right in the southern sky. It was still too dark to be out on the ocean, I thought. I had heard the tide come in, rushing watery over the mud flats, rolling stones on the beach as it marched relentlessly forward. A fisherman’s dinghy nearby was suddenly grinding over the pebbly beach, then floated free, but not too long later, I heard it grind out again. The tide was already turning, and it was only 4:30 AM.

Fundy tides

I got up suddenly with a real sense of urgency, packed my last gear, carried the boat down to the water, stowed and secured the packs, jumped in and paddled into deeper water and out of the bight. It was 5:00 by now and I had made it out. Breakfast will be a granola bar and water after sunrise, I decided.

The waning moon cast some light on the water, but not enough for me to see my chart. I had memorized the first 6 miles and had a rough time frame in mind also. It was eerie, lonely, but at the same time magical. At 6:33 the sun finally peeked over the eastern horizon and made everything much friendlier, even though the shoreline of the first 5 miles looked very foreboding: steep cliffs of gray slaty granite, interrupted only once by a huge power plant in Coleson Cove.

Split Rock was the next formidable point to round. The chart shows major tiderips. For a big boater that means stay way out, for me in my tiny 17 footer, hug the shore as close as you dare, just outside of the backwash, and hop from eddy to eddy. Don’t get swept up by the fast current, which will instantly develop standing waves, which with any opposing wind will give you major problems. A decisive hard paddle got me around that point and several others and across Musquash Harbor.

It was dead low by now and the usually submerged ledges loomed tall and black out of the water, extending their toothy arms way out into the bay.

Soon I was bucking the incoming tide as I rounded the last few points into Dipper Harbor. It is totally hidden behind big ledges and would be easy to miss, if it weren’t for the huge granite breakwater. Behind it was a significant dock with two floating dinghy docks and about 20 lobster boats. From my perspective the boat ramp at almost low aimed right into the sky. I opted to unload my gear at the ramp, but leave my boat on the floating dock, to save me two major portages.

I found a small spot of grass off to one side and was as usual hardly noticed. A quick call home to let folks know my whereabouts and a real bowl of fish chowder at the harbor restaurant made my day.

Only 16 mi today, 4:40 hours, no breakfast, no break - a very spartan day. The tides and the lay of the land had again decided my distance and time. I had to catch the ebb tide out of Fundy Bay and stop about one hour after low and definitely before the next point which happens to be the infamous Lepreau Point, the baddest point between St. John and Maine. The ledge points in Maces Bay seem to have an equally bad reputation according to the Canadian Sailing Directions for the Bay of Fundy.

I would need an early start again tomorrow - and no headwinds, please. The goal for that day would be Beaver Harbor, the last harbor before the entrance to Passamaquoddy Bay, which brings a completely new set of tidal rules to our equation. Tomorrow looked like a very challenging day, to say the least.

Big bad Lepreau Point

It was Saturday, August 19, 2000, the seventh day of my trip. I was on the water at 5:11 AM, no moon or stars out, a gentle drizzle, but almost calm - what a gift for a small boater. But the absolute dark was eerie. What was I doing out there? I had to cheer myself up by singing an old Viking song I learned in Germany, about making a passage in the dark of night in a big sea: “Nacht der schwarzen Wogen...” I had barely gotten used to my surroundings, and the second verse of my song, when the first fast current off Fishing Point grabbed me just 30 feet off shore and tossed me about. That was my wake-up call and snapped me out of my early morning grogginess.

I was then headed down to the bright lights of the nuclear power plant at Lepreau Point. I hugged the shore and felt like Dirk Pitt in the many Clive Cussler books, either protecting or penetrating a nuclear power station or secret military installation. And I wondered whether I would show up on their radar or whether guards were patrolling the premises and already had me in sight with their night vision goggles. Should I worry about that? Naah! No interceptor boat came rushing towards me, no megaphone blasted warnings. Only a friendly looking candy cane lighthouse greeted me at the point (2 red stripes on a white lighthouse).

I made it into Maces Bay much nicer than anticipated and never allowed the famous Point Rip to catch ahold of me. Maces Bay was a problem of a different kind. It has several long bars, extending up to 1.7 miles into the Bay towards the SW. They were distinctly coming out when I got there, but I still hoped to make it across the first one, right in the middle. It would save me a lot of time, not to mention anxiety of being out there all alone in the dark.

Ledgy fingers of Maces Bay

Thousands of Eiders squawked and scampered around these toothy reefs. It sounded like waves breaking on a shallow beach when they took off. I found just enough water to scoot across and set a course for the Salkeld Islands, otherwise known as The Brothers, two big 80 foot tall chunks of granite, flat-topped and grass-covered, with very steep sides - extremely elemental and glacial looking. I pressed on to reach shore again, which was Barnaby Head. I had gone 10 miles so far, and the tide was still ebbing. I felt I could afford a brief 10-minute break for breakfast and map reading. But I was itching to go on again and get to Beaver Harbor before the tide turned and made going so much harder.

It turned at 9:00 AM, which left me 1:45 hours against the incoming tide around East Point and many other exposed ledge points into the harbor. I had whittled the 25 mile distance down to 22 by shortcutting bars and some bays, and made it into port after 5:33 hours with only one brief 10 minute stop, which gets me back to my usual speed of 4 miles/hour or 15 minutes for each mile. It was only 10:44 AM, but I was done for the day. What luxury, having the whole afternoon to myself.

I first arrived at the town dock where a mackerel tournament was in progress, right off the tall pier. I phoned, talked to people, but since there was no place for me to camp out for the night, I headed out again towards the small crescent beach just inside the lighthouse. It was perfectly protected from the ocean swells, and the seawall high on the beach was just wide and level enough for my little tent.

Salmon farming in Beaver Harbor

Wild roses and sturdy thistles flanked my tent on either side. Swimming in the cold water at high tide is a routine for me, just to remind me how cold it is if I should fall in, or better, to make sure I do not go swimming off the boat, i.e. dump. Then coffee, reading, studying rocks, plants and birds and watching the salmon jump in their netted enclosures in the outer harbor. When the sun finally came out that afternoon, life felt good, also because I was getting closer to known territory, Passamaquoddy Bay, my goal for tomorrow.

Passamaquoddy Bay

I had to plan everything right again, or I would not be able to pull it off. So here is what I figured that afternoon. One: I had to get into Passamaquoddy Bay - staying outside of all the islands, even though it is shorter, is just asking for trouble; I knew better. So I had to make it to the Letite Narrows, the eastern entrance, at dead low and flush into the bay with the first of the flood tide and get out of Passamaquoddy Bay the next day at Lubec with the end of the ebb tide.

Both Narrows have very strong tidal flows, 5-8 knots, and are a real doozie. Two: I did not necessarily want to go around the entire bay, but would prefer to hug the NW shore of Deer Island instead, and then hop across the 1.3 mile wide Western Passage to Perry, ME, USA. I figured I had to leave at 6:30 AM the next morning to get to Greens Point/Letite Passage at 9:00 (low tide) and hope to catch a manageable tide across Western Passage to Perry; if not, I would hole up on the island.

It was Sunday, the night was calm and quiet till 4:00 AM, when suddenly the fog horn started blasting me off the sea-wall. FOG? Who needs that on a stretch like today which needed perfect planning and perfect execution. I tried to stay calm and pretended the fog and the horn were not there. I was so successful at that, that I even missed my alarm. Breakfast got scrapped again. Instead I packed my gear, got in the boat, and clung to the few positive aspects of my situation: it was light, there was very little wind, no rain and I could still see shore.

I made it fine to Deadman’s Harbor, but had to steer a compass course across the bight and then literally feel my way along shore to the lighthouse at the entrance to Blacks, Letang and Bliss Harbors. At that point the fog bank mercifully shifted so I could make out my intricate course through Bliss Harbor to White Head and the lighthouse at Greens Point, the entrance to Letite Passage. I was right on time, 9:00 AM sharp, but the tide was still running out hard. Big bays often have delayed tides as in St. John, but that was OK by me. This gave me time to crunch down two granola bars.

10 minutes later I felt itchy again and set out to ferry across the still very strong ebb flow and went due west to Mohawk Island, then between MacMaster and Pendleton out Little Letite Passage into Passamaquoddy Bay. A hard paddle, but it felt great being in the big bay with the sun coming out. Who would have thought it this morning! From there it was 6 miles straight down the NW shore of Deer Island, past lots of salmon pens to Calders Head, and then a surprisingly easy 1.3 mile hitch across Western Passage to the boat ramp at Perry, ME.

Sunrise way down east

I was back in Maine, USA. I was elated and cheering myself while I was portaging my gear and boat to the high grassy ground beside the ramp. The small apple tree was still there where I had pitched my tent on my trip down the St. Croix River in 1997. 20 miles in under 5 hours, I was cooking today, and it was still before noon. Going on because it was still early in the day did not even occur to me. The tide was coming in hard and there is absolutely no way to get down to Lubec under these conditions. I had also listened to the marine weather report, and they were right on as usual: suddenly the wind picked up, the sun disappeared, black clouds with corkscrews hanging down from them darkened the sky. Then it rained, accompanied by thunder and lightning. I felt snug and smug in my tent, enjoying my coffee and last chocolate chip cookie and planning the rest of my trip back to Machias, ME.

Last leg back to Machias

I would have to catch the last of the ebbing tide at Lubec tomorrow and hole up somewhere inside of Quoddy Head Narrows, because by then the tide would be running in strong and it would be useless tackling the very exposed formidable 20 miles of coastline towards Cutler. Another 12-mile day tomorrow, like St. John to Lorneville. So be it. The rest should fall into two perfect days of 20 miles to Cutler and 19 miles from there to Machias, both on the early morning ebb tide express again.

I was off at 7:00 AM EST the next morning with the ebb tide pushing me towards Eastport. I heard rushing waves on my left all the way down Western Way, steering well clear of the Old Sow, the largest whirlpool in the world, according to the Sailing Directions. I wanted no part of it. Right then I met two ferries from and to Deer Island going sideways through the fast current.

I appreciated when one ferry slowed down somewhat to go behind me instead of crossing my bow like most other powerboats have done, on this and past trips. What is it with those guys? From far on the horizon they seem to aim for you in your little boat, then cut right in front of your bow leaving you floundering in their wake. I do not get it. - Thanks guys.

At Estes Head I encountered the strong ebb flow out of Cobscook Bay and prudently but swiftly ferried across to Treat Island. I liked the fact that it was still ebbing. I had figured everything right again, I thought. Great! But my bubble burst one mile later when I was about to enter Lubec Narrows. I had allowed an extra 30 minutes and was even ahead of schedule, but the tide had already turned. OH NO, I thought, I’ve got to get out of here, and I pressed the panic button. As fast as I could I eddy hopped towards the Campobello bridge and the Customs station on the right to check back into the US. I had missed the ten- minute window of slack tide the US Coast Pilot and the Sailing Directions mentioned, and I was quite upset with myself about that, for a moment anyway.

Surprise # 2: There was no customs station dock, or any dock for that matter, and the bay on the other side of the bridge was reduced by extensive mud flats to a narrow winding 1-mile-long channel leading to an in-water lighthouse. I could not possibly stop or get out. So I ripped out my passport, waved it in the direction of the customs house farther down along the road, and kept on paddling. (I had to ease my conscience; not that I thought anybody could see my passport and would OK my procedure. You understand, don’t you?)

Major mud flats and mussel beds right and left pushed me further into the bay towards Quoddy Head, and since no boat was chasing me, I gathered I was OK and went on. Just inside the point I found a nice level grassy field with what looked like a footpath up to it. I beached my boat on a seaweed-covered ledge and explored the options. It looked great, but how do I get there at this low tide?

It looked impossible and for a brief moment I wished it was high tide. But then it would be low in the morning. What a silly thought anyway - you take what you get and make the best of it. And I did. I secured my boat and went exploring, then wrote my trip log of this morning, had a granola bar, tried to find the gray seals I heard across the bay with my binoculars, watched the ferry from Blacks Harbor to Grand Mannan Island and The Wolves, an off-shore group of small islands, every time hitching my still laden boat higher up on the seaweed-covered ledges.

When I finally ran out of things to do, I decided it was time to get ashore. I dragged and slid my boat over a more level area to a point where I felt I could begin portaging the whole shebang. At that point I noticed that my rudder had come off. The pivot bolt had come out and had disappeared in the seaweed. Well, better now than rounding a point, I thought, and replaced it with a spare bolt I carried with me.

The place was great, giving me plenty of solitude and time for some good reading, resting and looking around. High tide came right up to the last ledge outcropping, leaving just enough room for my boat above the high-water line.

Next morning I was off by 4:40 AM without breakfast, because the tide was already running out. Half an hour does make a difference in these waters and makes for a much longer portage. I also prefer to put in on clean rocks, not the slippery seaweed-covered boulder field below it. Orion and the last quarter of the moon plus near calm conditions also made me eager to get started and get around Quoddy Head, past the red and white striped lighthouse and across the bar leading out to Sail Rock. At certain tides a heavy tiderip occurs here. I have seen a storm break on this bar from shore some years ago, and it was awesome.

All went well this morning, mostly along a high, rocky, precipitous shoreline. And then the sun came up with a truly spectacular array of light filling the entire eastern sky. The first sunlight to hit the US on this day, I thought to myself. I stopped to take pictures and noticed Grand Manan Island in the distance, big, gray and menacing, as it funnels the tidewaters through this channel, ebbing at 2.2 knots, flooding at 2.8.

This easternmost stretch of the American coastline is a formidable and remote piece of real estate. I have always had the utmost respect for this part of the Maine coast. I never made it out here with my little 22-foot sailboat, but now I was going to do it solo in a 17’ sea canoe. There are a couple of bights like Bailey’s Mistake or Moose Cove, but no real harbors, just a few houses and fish weirs and arctic gray seals on the ledges at the entrance to these two coves.

I fondly remember these big bruisers from last year’s trip around the Gaspé peninsula in Quebec, Canada. They are so much bigger than our ubiquitous harbor seals, and their heads have a very distinct horse-like shape with a long rounded roman nose. I also saw numerous ravens and eagles along this remote stretch of coast.

Then Western Head appeared in the distance, at first looking like an island. But when you see the lighthouse on Little River Island you know you are at the entrance to Cutler Harbor. It was still ebbing and I could have gone on, but why. I had already paddled 20 miles without a break in exactly 5 hours - that was enough. It left a perfect 19 miler for tomorrow, and I had to find a phone to set up a pick-up in Machias for tomorrow anyway.

I left another message for Nancy, hoping she could meet me at the Machias town dock near Helen’s Restaurant at high noon tomorrow, the same place where I finished my MIT trip from Portland, ME in 1996. After the call I found a seawall across from town out towards Western Head and enjoyed the afternoon, except for the long portage out. I consoled myself with every trip that tomorrow morning would be easier, downright fun with the tide practically up to my tent.

Later that afternoon an older fellow on a 4-wheeler stopped by to check me out since I had apparently set up camp on his land. I didn’t know that the seawall could be considered part of anybody’s land, but after the Moody Beach settlement, things have changed in Maine. In New Brunswick, people assured me, nobody can own the immediate shoreline, and I liked them for that attitude. This rough looking fellow told me that his mother worried about “what kind of a hippie was camping on her beach?” He went on to say that “times aren’t what they used to be. You’ve even got to lock your doors these days”. I told him what I was doing and asked him to assure his Mom that I was no hippie, and would be gone before sunrise tomorrow.

Those were the words he wanted to hear, and he let me stay. No dinner at the house, though, but rather one of my last cans of Bush baked beans, a small can of fruit and a brisk walk to the point along a Maine Coast Heritage Trust trail which started about 100 yards beyond my tent.

I was off by 4:43 AM again, some stars and minimal moon as yesterday and calm - a promising start. High tide though should have progressed 50 minutes each day, but did not, according to my observations. High was about 3:30 this morning and it was definitely ebbing when I put in. (The official tide calendar would have been handy, but I am a dead-reckoning, eyeballer, not GPS and cell-phone kind of guy.)

As soon as I rounded Western Head and Great Head, the 26 radio towers of the Cutler Naval Station came into view, a leftover from the cold war - a submarine tracking station. The two tallest ones measure 1025 feet, according to my chart.

I was duly impressed by the magnitude of this installation and had to take a picture to show my family and friends. It was so big, I barely got it in my camera viewfinder.

Cutler Naval Station

Then for the next 2 miles, I felt someone in a Jeep was shadowing me, stopping at times, even getting out of the car, looking at me through field glasses, hiding behind alder clumps, till I finally headed into the bay proper between Sprague Point and Chance Island.

Arrival in Machias

At this juncture I noticed that the ebb tide was no longer helping me along, but was distinctly against me. But that could not be helped. The river ebbed even harder between Salt and Round Island and all the way up to Machias, but I could not wait to get there and finish this trip. And then, after the last big mud bank on the left and the outflow from Middle River on the right, there it was, the town ramp, all dry and grounded out on a slimy, slithery concrete ramp. I had made it: 19 miles today in under 5 hours, no granola breaks, no breakfast either for that matter, and it was only 9:35 AM.

I lugged my boat and gear to the head of the ramp and went over to Helen’s Restaurant for a real cup of coffee and a stack of blueberry pancakes. And as I was sitting there at a window table, keeping an eye on my gear, enjoying my mountain of pancakes and endless supply of coffee, it suddenly occurred to me to check with Nancy about the pick-up. The last two phone calls were only messages. Had she gotten them? Could she come? Nobody was home again, which could only mean she was on her way, I thought confidently. And as I was thinking this, finishing my umpteenth cup of coffee, she drove up to my gear, looked around, saw me wave from the window and we met half-way. What a sweetheart, and thanks again for all your support.

Summary

This brings this trip to an end also, 220 miles in 11 days, 20 miles on the average, a few miles less than my usual 25 to 27 miles. But this stretch of the Atlantic was different. It required careful planning and timing because it allowed only a very limited window for canoeing, either the ebb or the floodtide plus 1 hour perhaps.

You have to go with the flow, in my case, use the ebb tide express and never force the issue. Yes, and do try to avoid the fog, or the Bay of Fundy will bite you.

The shoreline along the Bay of Fundy, if you can see it, is spectacular, stark and beautiful and still unspoiled for long stretches, but remember, it is not very forgiving and therefore this is not a trip for beginners. Doing the Maine Island Trail is difficult. Anybody who has done it will attest to that. The stretch beyond the MIT to the south from Boston to Portland, however, is more difficult, since it is much more exposed. The stretch from Machias to St. John, I found most difficult, but for the same reason also most rewarding, which makes it the top challenge of ocean kayaking and sea canoeing around. That’s why people do it, I guess. My bottom line, however, is to make sure I am having fun doing these feats, every day, that is, and not get obsessed, hung-up, or angry if things do not work out right.

Whenever I canoe a new coastline, I always have a well-thought-out and doable plan A, but also a plan B and even C. I don’t like to set myself up for failure and I do listen to the little voice inside of me and know when to quit. As long as I have confidence, I can do it; when that goes, I prudently bail out. (All of the above is called experience, in case you hadn’t noticed.)

So what is next? After having completed the 570-mile stretch from Boston, MA to St. John, NB it seems logical to continue deeper into Fundy. But I don’t think I would enjoy canoeing around the rest of the bay. The tides are simply too significant the farther you get into Fundy, up to 55 feet, the highest in the world, and that greatly restricts one’s paddling time and makes putting in and getting out nearly impossible. Being stuck off-shore with 2 or more miles of soft, oozy, sandal-eating muck between you and terra firma does not appeal to me, and doing it only so you can say you have canoed around the entire Bay of Fundy is not worth my valuable time, being 61.

But how about the Bras d’Or Lakes or Mahone Bay in Nova Scotia, or the northeast shore of NB between Shippagan and Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia? And how about some inland-ocean paddling on the Great Lakes, let’s say from Duluth to Grand Portage for starters? There are endless possibilities...

**************************

Charts - Canadian: #4142, 4141,4116

American: #13398, 13394, 13326

Guides - Canadian: Sailing Directions, Nova Scotia (Atlantic Coast) and Bay of Fundy

Bay of Fundy Tide and Current Tables (which I should have had)

American: United States Coast Pilot (Atlantic Coast)

Duncan/Ware: A Cruising Guide to the New England Coast

Special equipment: VHF marine radiotelephone with weather channels

Distances are given in statute miles

© Reinhard Zollitsch

BACK TO TOP OF PAGE