By Reinhard Zollitsch

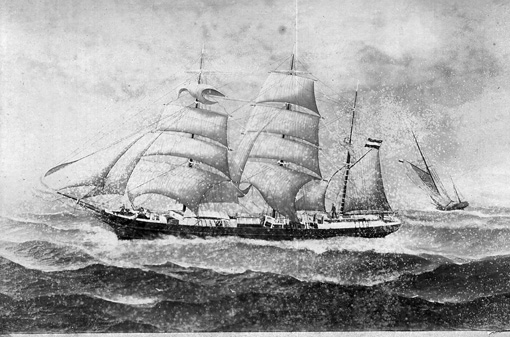

Growing up in northern Germany, I fondly remember Saturday afternoons – school was over at noon, I could play soccer, watch the big ships come through the Kiel Canal or visit my grandfather, the old sea captain, now retired. He had sailed on windjammers to Australia and around the Horn to Iquique, Chili in the lucrative but smelly and messy Saltpeter trade (guano - “bird sh-t” - sorry) for fancy British gardens. Towards the end of the war (WWII), he was pressed back into duty piloting boats through the mined approaches to the harbor of Kiel and the Kiel Canal, a job, as he told me, that first taught him accurate navigation.

"Minna Helene" bound for Chile, South America (1892-94)

He was full of adventure stories and also knew some English, which interested me as a young kid and which made me become an exchange student in a British private Prep School (Lancing College, near Brighton) for a term, when I was in high school.

Opa Zollitsch at the helm (1923)

My Grandfather, Willi Zollitsch

Needless to say, I was interested in the sea and boats - ocean-going boats and far-away places – but did not have the opportunity to do anything about it till I started college in the harbor town of Kiel, on the Kiel Canal connecting the Baltic Sea with the North Sea and the Atlantic. The year was 1959. I started small the first two summers, paddling Eskimo skin boats, rowing racing shells, skulling in “fours”, as well as sailing various types of dinghies.

For the following summer I got a seaman's passport and worked for 2 months on a 1,000-ton freighter shipping between ports like Rotterdam, Antwerp, Amsterdam, Hamburg, Lübeck and the Swedish port of Sundsval/Timråa, way north in the Gulf of Bothnia sea arm of the Baltic Sea. We were mostly picking up bundles of raw wood pulp sheets, the size of a 4X8 sheet of plywood, for paper refining mills in Belgium and Holland. Our return cargo was bulk bleaching salt, which was a nuisance for us crew to wash out of the hull after unloading at the Swedish paper mills.

1,000-ton North Sea/Baltic Trader "Siegerland"

RZ on look-out up the mast

Once we loaded grain from Hamburg, but the most interesting cargo was split rock, granite, from a no-name harbor/place in southern Sweden. I remember security guards came aboard when we approached shore. Small tugs then helped turn our freighter around, and backed us into a “hole in the wall”, a cleft in the granite shoreline into a big granite-domed “harbor” with docks, cranes and buildings, and lots of people busily running around our boat.

It was truly Bondian (“James Bond”), even though at that time I had no idea what that meant. It seemed very secretive. Having grown up during WWII in the German submarine port of Kiel, I knew what this was: a natural bunker for submarines. So perhaps the neutral country of Sweden, I thought to myself, was planning on protecting its aquatic turf of the Baltic Sea from the “communist aggressors”. This was the height of the cold war, remember. Later that same summer (August 1961, to be exact), the Berlin Wall was built, an event which I had to see to believe.

So we loaded up with 1,000 tons of crushed rock for German railroad beds in Lübeck, and were gone by morning, and I could never persuade the skipper to show me on the chart where we had been. Other navigational challenges for me were going through the Kiel Canal at night (it is about 60 miles/100 km long, with two sets of locks), and up the winding shipping channel of the Schelde River to Antwerp, Belgium.

I again had the midnight watch from 12 midnight to 4:00 am. There were flashing, blinking and directional lights everywhere, red, green and white, warning of the boat-eating rocks and mud flats at every bend in the river. I was sweating at the wheel, being new to the job and tired from 8 hours of painting on deck. To boot, the pilot's German was more Flemish than “Hochdeutsch” (standard German). Yes, 8 hours on deck plus 4 hours at night – 12 hours on duty every day, very tiring, even for an eager young whippersnapper like me.

Encountering force 11 winds (12 being hurricane strength, 74 miles per hour) on the open Baltic, however, was exhilirating for me. We stuck the bow into the waves, and solid water crashed across the deck from one side of the ship to the other. We assured the skipper that we had battened down the hatches properly, while keeping our fingers crossed behind our backs.

Force 11 storm on the Baltic Sea (Siegerland)

My grandfather died while I was working on that freighter – I missed the funeral, but instead promised him that some year I would cross the Atlantic, as the old man had done so many times.

That time came sooner than expected, the following year, that is. Being an English major at the University of Kiel, I felt I owed it to my future students to have lived in both England and the US for “a significant span of time”. So I applied for a graduate assistantship at 3 US east coast colleges (in Virginia – I was fascinated with Jefferson; in Massachusetts – I was interested in the Transcendentalist writers in the Boston area; and in Maine - Grandfather had told me about the ship building and sailing traditions of that state).

Having the luxury of choice, I of course started out in Maine, since I knew absolutely nothing about that state. I got my master's degree in English there, and later a MA and Ph.D. in German from the University of Massachusetts. I did not meet Jefferson's inquisitive spirit until 2003 on my Lewis & Clark venture down the Upper Missouri River (see my L&C article in the Oct.1/15, 2003 issues of MAIB, and on my website).

But one big problem remained in my US venture: with limited funds, how was I to get from northern Germany to Orono, Maine by Sept. 1 of that year (1962)? I again chose a very direct route: I went to the Hamburg harbormaster, showed him my seaman's passport and asked him whether he knew of any boat going from any port in Europe to any east coast port in the US, one-way only. (Not until now did I realize that I never gave any thought to how I would get back to Germany when my assistantship ended - well, as it turned out, I didn't go back. I am still here in Maine 47 years later.)

He smiled, we talked and found out we both had gone to the same high school in the small town of Rendsburg and had recently sailed in one of the biggest sailing regattas in Germany, the Kieler Woche, in the same race, in the same class, but on competing boats. He won (on Germany's top ocean racer Germania, owned by the Krupp Steel Co.), beating us 12 over-eager students coaxing every ounce of speed out of our 60' transatlantic racing yawl (the Peter von Danzig, built in 1935 for the race from Bermuda to Germany as part of the 1936 Berlin Olympics).

10,000-ton coal freighter Rhenania in Rotterdam

It worked, and there I was, suitcase in hand for a year's stay in the US, at a coal dock in Rotterdam, to board the 10,000-ton coal freighter Rhenania hauling anthracite coal from Norfolk, Virginia to the mouth of the Rhine River. The coal was still being transferred to 1,000-ton river boats (lighters and barges), which would then either steam up the Rhine River on their own power or be pulled up in long convoys.

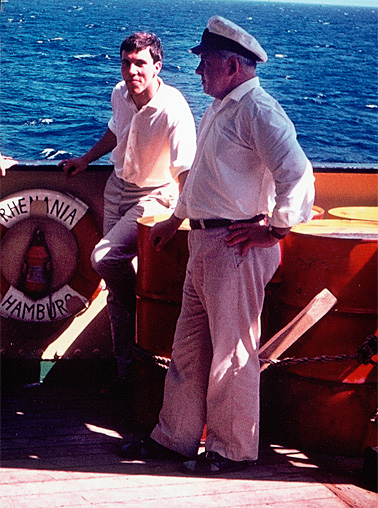

On the open Atlantic (Rhenania)

The skipper and the officers of the Rhenania were very kind to me on board, treating me more like a trainee and using me to break their monotony of running across “the pond” in ballast for 10 days. They showed me everything from navigation to how they were using the new heavy fuel for their engines.

I did a lot of good listening. Even though I had a student's visa for the upcoming academic year, at that time American immigration was not allowing any foreign seaman to step ashore. So I was listed as a passenger and had to pay the skipper 10 Deutschmark per day for room and board, or DM 100 for the 10-day crossing (about $25 at the exchange rate then), to be perfectly legal.

RZ with skipper

Norfolk, VA - harbor pilot

All worked out fine, and the rest was easy. I was taken to a Greyhound station in Norfolk and took a bus to New York, Boston and Bangor, Maine eventually, also briefly stopping at Harvard and Yale, which I had to see, being a conscientious, aspiring graduate student. My German/International youth hostel pass also kept me in good standing at the YMCA in New York, New Haven, CT and Boston, MA. The local Bangor bus driver even dropped me off at the professor's house where I had to report to, in Orono, the University town for Maine. He was not there, but his 19-year old daughter Nancy was...

The rest is history. And yes, Grandfather, I eventually did sail across the Atlantic (in 1977), on a real wooden two-masted schooner as a watch captain (see: “Fiddler's Green Across the Atlantic”, MAIB, July 15, 2003, and on my website). I also have my own little 22' sailboat in Maine, and in recent years have paddled 5,000 miles (8,000 km) around all New England states and all Canadian maritime provinces, including up the western shore of Newfoundland, in an even smaller man-powered boat, a solo sea canoe. I share my stories with family, friends, and the readers of various boating magazines as well as my website.

You, Opa Zollitsch, surely inspired me to do all those seafaring adventures, and the sea stories you told me as a little wide-eyed kid are now bringing out my own boating stories.

I recently noticed with pride, that I have become you: I have become a grandfather of three grandsons aged 1-4 and suddenly find myself at the helm where you used to stand, just as in Hermann Hesse's lovely river story Flötentraum (Flute Dream). And like you and "the old man" in the Hesse story, I am now guiding the family boat and telling my tales of the sea and open horizons, of long journeys and happy arrivals. At this point in time, though, my three grandsons are still too young to be impressed by my stories or hearing about you and your windjammer adventures. But maybe some day...

RZ at the helm of schooner "Fiddler's Green" (1977)

© Reinhard Zollitsch

BACK TO TOP OF PAGE