June 2004

By Reinhard Zollitsch

Celebrating 400 years of Acadian presence in North America

On May 14, 1804 Lewis and Clark led the intrepid Corps of Discovery from the confluence of the Missouri River with the Mississippi to find a waterway to the Pacific. They were to report back to President Jefferson about the newly acquired Louisiana purchase and beyond, and they did, with comprehensive trip reports, drawings of scenery, animals, plants and people, as well as extensive charts. That was 200 years ago and without a doubt the beginning of a new era. (See my “L&C + 200” article in MAIB, Oct.1/15, 2003.)

We have to go back another 200 years exactly, to witness a similar feat with the same importance for what is now known as the US and Canada, the first permanent settlement of north Europeans on the eastern shores of the Atlantic (north of Florida). 400 years ago, on June 26, 1604, to be exact, Pierre Dugua led 79 French settlers and traders to a small island in the St. Croix River along the present day CAN/AM border (between Maine and New Brunswick) to establish a permanent trading post in the new world.

The 400-year celebration

In return, the King of France, Henri of Navarre, gave Dugua a trading monopoly in the lucrative fur trade and the title “Lieutenant General of Acadie”, on top of already being a noble with the title of “Sieur de Mons”. With that act, French Acadia was born, which, together with the founding of the city of Quebec by Samuel de Champlain four years later, is the cradle of today’s 18 million North American people of French descent.

The Vikings were different

It is of interest to note that the landing on St. Croix Island predates the first British settlements of 1607 in Jamestown, VA, as well as the Pilgrims’ leap off their Mayflower onto Plymouth Rock in 1620. Sure, everybody knows that “in fourteen hundred ninety-two Columbus sailed the ocean blue”, an event with monumental consequences, but he did not stay. He came, he saw and left again, like so many other early Spanish and Portugese explorers.

And so did the Vikings, by the way, around 1000, touching on “Markland” (Labrador) and “Vinland” (Newfoundland) following the receding walrus herds, and looking for adventure. They had no intentions of settling on these shores, but rather establishing seasonal hunting and fishing stations like the Basques and Portuguese had done before them, maybe even before Columbus, but certainly before our Pilgrim Fathers.

The Vikings, according to Farley Mowat’s Westviking, were also strangely afraid of the native Beothuk people and were very reluctant to settle on their turf. The Viking camp at L’Anse au Meadows at the Straits of Belle Isle (between Labrador and Newfoundland), so he thinks, was only a temporary camp, home base for a group of “later Vikings” looking for Leif Eriksson’s fabled “Vinland”, the land of wine and roses. Leif never told anybody where it was exactly, not even his own sons. (He may have had a very good reason for it - he may have made up the embellishments in true Viking fashion!)

But the Vikings, according to Mowat, decided to look for it anyway and established a search camp at L’ Anse au Meadows, from where they fanned out to check both the eastern and western shores of Newfoundland as well as the southern shore of Labrador. But when they did not find the “promised land”, they broke camp and returned to Greenland, which likewise was everything but green - another euphemistic misnomer.

The first French Acadian settlement

Unlike the Vikings, the French 1604 expedition came over from today’s LeHavre in five big sturdy sea going ships, full of building supplies and provisions, trading goods, tools, arms, even guns. They meant business; they came with a purpose. This was no raiding party; they weren’t buccaneers or pirates, but peaceful settlers and adventurous traders, but willing to protect their turf against other raiders and the native population, if necessary.

No, they did not ask permission from the Passamaquoddy, the Malaseet or Micmacs to land on this modest little island, but they also did not drive anybody away. They tried to establish a good rapport with the local tribes, as the French have always done, especially in Voyageur country, because they needed them as guides and trading partners. The French group of 79 was totally convinced they were bringing the “locals” a better life with the spoils of European culture, as well as saving their souls with Christianity, Catholicism that is. As they saw it, it was a win-win situation, but just in case, they brought some guns to protect their turf, mostly against other European raiders, like the British, the Spaniards and the Portugese.

The St. Croix group, I read, was part of a larger French project of five ships and 120 men, all making a first landing on Sable Island off Nova Scotia - what a feat in itself! From there, two ships with 41 men aboard went towards the St. Lawrence to trade, one ship went to Canso, NS, and the remaining two ships and 79 men, led by Dugua and Champlain, explored the south coast of NS and the Bay of Fundy. They all liked the Annapolis Basin area, but decided instead to try their luck on the other side of the tide-ridden Fundy Bay, on a small island in the tidal part of the St. Croix River where it empties into Passamaquoddy Bay.

Champlain's model

A great choice for a settlement, but...

What a decision, facing a new venture in the new world, with new people, in an area often shrouded in fog and surrounded by extreme tides. Why would anybody choose a place like that? I felt I had to revisit Passamaquoddy Bay in my trusty canoe to check things out and reread Champlain’s trip reports and other pertinent literature to inform myself. So I spent the last four days (June 10-13, 2004) on and around this little island at the mouth of the St. Croix River and the greater Passamaquoddy Bay area, to get reacquainted with the lay of the land of one of my favorite haunts.

I was impressed right from the beginning that the ships made it across the North Atlantic to Sable Island so early in the season and found their way into Passamaquoddy Bay. Cabot (1497) as well as Verrazano (1524) and Gomés (1525) may have sailed by here. Even if our intrepid group of French traders and settlers had heard about this huge tidal bay, it is still difficult to find, and even harder to get in.

There are only three very small rock- studded openings into the bay, through which the nineteen-foot tide gushes with a 5-8 knot vengeance. They had to have been good sailors who had learned their lessons from the Fundy-like tides in the Bay of St. Malo in Brittany, the home of Cartier, by the way. They even knew how to use the tides to their advantage, i.e. use them as protection against unwanted intruders. At ebb tide their bay was safe - nobody could get in. The ebb flow would act like a gate. (Their later camp at Port Royal, Nova Scotia, by the way, had the same tidal set-up, with Digby Gut keeping out intruders for nearly 12 hours each day.)

The second plus point for establishing a colony here, as I see it, was the fact that Passamaquoddy Bay is huge, with lots of lobes, and that means lots of shoreline. It is wooded and yet is conveniently interspersed with shoaling sandy or at least gravelly beaches. It abounds with fish, seal, porpoise, duck, clams and mussels, and the woods look promising for game and their fur trade. The fog also mostly hangs around like a thick shroud on the open Bay of Fundy, again making it hard for intruders to find. Yet another plus point for the intrepid sailors - they had done their homework.

St. Croix Island itself also looked very promising. There was good anchoring and landing, and a higher field for the settlement with lookout point. The settlers could feel safe on their island, and shore was real close on all sides. It was a natural fort in more than one sense.

So what went wrong?

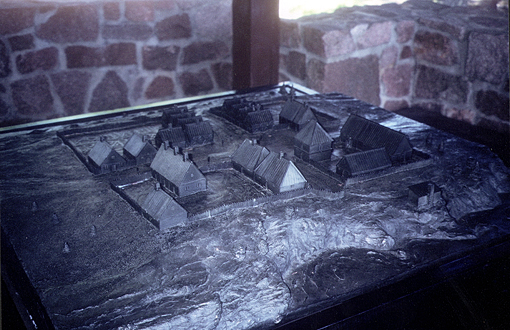

In August the supply ships left for France, leaving the settlers full of hope to make a go of their venture. According to Champlain’s drawing of the place, they started building a real settlement with roads, houses, church, gardens, all surrounded by a palisade fence. The model in the present park looks real cozy and promising. So why did the settlement fail, all on its own, in less than a year? What went wrong? They were great sailors, but where is their basic mental miscalculation?

All literature I have read on their failure points to the especially harsh winter that year or blames it on the cold north wind in that region. The settlers’ miscalculation must have been much greater to cause such havoc among the 79 men. And then it came to me: They were sailors at heart, very good ones at that, and in those days sailors navigated and thought in latitudes, north-south reference points.

They knew most of the latitudes of most of the bigger harbor cities in Europe and beyond, by measuring the angle from the horizon to the North Star, the “Guide Star” for the North Atlantic. Up here in Maine, for example, the North Star is quite high in the sky, while looking at the same star from the Everglades makes it appear to have risen just above the tree line.

In early navigation, relative north-south fixes were determined by the angle between the horizon and a fixed star, like our North Star. Longitudinal fixes, on the other hand, remained guesswork till sailors got their hands on more or less accurate chronometers, and they weren’t invented till 1714. East-west fixes, as you may remember from any navigation class you may have taken, are based on the course of the sun, i.e. are time-related, with Greenwich, England, being the mathematical point of departure, the “trans-polar-equator” if you want to picture it that way.

Latitudinal thinking

So here is my reconstruction of their thought process: St. Croix Island, according to their correct measurement, is at about 45 degrees north, half way between the north pole and the equator, which to a Frenchman would put it into the wine growing region of Bordeaux (also at 45 degrees north), or right in the middle of the Gulf of Venice in the Adriatic Sea in Italy, a very familiar latitude for Europeans.

What a climate, they must have thought. No problem! From their new home on St. Croix Island they could row over to the nearby shores and fetch water from the rivers or streams and go hunting and trapping all winter. Saltwater just does not freeze, definitely not near Bordeaux or Venice, right?

But it did, and with a 19-foot tide, this was not solid ice but shifting pack ice, impossible to traverse. They were trapped on their own island, held hostage by the winter, and slowly starved and froze to death when their supplies ran out. Their diet was also missing one important ingredient, vitamin C, like in oranges, lemons and limes, which the “Limeys” (British sailors) learned first, but also not until 1753. Many settlers on the island were weakened or struck down by scurvy. This was a major miscalculation for which they paid dearly. 35 of the 79 settlers died, and 20 more had to be nursed back to health when the supply ships returned the following June.

View from St. Croix Island - so near and yet so far in winter

How did it happen? In 1604, people had no idea that 45 degrees latitude on the western Atlantic shore is not the same as on the eastern, the European side of that ocean. Nowadays most Americans know, for example, that living in Maine is quite different from living in Washington State. Maine has a cold continental climate, while Washingtoin State is majorly influenced by the ocean to its west. The same is true for the comparison of Maine with Bordeaux in Southern France or Venice. The latter European places are heavily influenced by the ocean, like Washington State, and the Gulf Stream in particular.

With our easterly drift of weather systems, you would thus encounter a very cold climate in Maine, (caused by a huge land mass to the west, which cools very rapidly), and a climate affected by a much slower cooling ocean in Washington State or in France. Furthermore, if early ocean travellers noticed the Gulf Stream on their way over, or heard about it from early explorers or fishermen, they must have thought it should have a much more significant effect along the shores it originated from than on the distant European shore.

So you see, according to their knowledge, they had everything planned just right, but in the Spring of 1605 they knew they had made a bad mistake choosing an island in a tidal bay that freezes up, and knew they had to leave and try again somewhere else.

I admire those guys for being quick learners. It was not the north wind or a specially cold winter, as some people still maintain 400 years later, no, there was a basic flaw in their thinking, for which, however, they cannot be blamed. It was the climate! But even if they did not quite understand the reasons for the surprisingly cold Maine winter, they knew they had to get out of there and try again somewhere else, on shore this time, which they eventually did.

What now?

So they scouted the entire coast south to Cape Cod, but decided in the end to return to one of their first stops, another tidal inlet off the Bay of Fundy, up through tide- ridden Digby Gut, Nova Scotia, again for protection. So they packed up whatever they could, loaded it onto the two supply ships, which returned as arranged in late June the next year, and sailed up to the mouth of the Annapolis River. They called their new settlement Port Royal.

From there the Acadians moved to other enclaves in Nova Scotia, along the Gulf of St. Lawrence in New Brunswick, the southwest shore of Prince Edward Island, up the St. John River, and, yes, to other parts of Maine also. They were a very peaceful, pious and accommodating people, till the British so rudely, even cruelly, deported them between 1755-1778 in an effort of ethnic cleansing.

The Acadians were driven out of their homes by the thousands, shipped back to France or expelled, and finally resettled wherever they were welcome, including Louisiana, where they established their new “Cajun” (Acadian) culture, language and life style. (Try to remember Longfellow’s poem Evangeline from your high school days, and you know what I am talking about.)

The 400-year celebration

Driving up towards St. Croix Island this June 2004, I was not surprised to see road signs pointing to “DOWN EAST AND ACADIA” the closer I got to this historic place.

I found a new, very well-appointed little park at Red Beach in Maine, on route #1 about 10 miles SE of Calais/St. Stephen, right across from the island.

I loved looking at the model of the settlement (I have always loved models, ever since I was a kid) and pictured myself in it, taking notes, recording events, and most of all charting everything I saw - like Champlain, you guessed it. There were lots of explanatory tablets, and life-sized statues of settlers in the woods watching me as I took the self-guided tour. On the other side of the bay (on the Canadian side) off the route to St. Andrews, you will find a much bigger Information Center explaining the significance of St. Croix Island for Canada.

As a matter of fact, the Canadian Maritimes are caught in a festive frenzy this summer. You will find celebrations with Acadian music, dancing, food and lots of tricolor flags accentuated by the gold star of the Acadians. Halifax even sports an international tall ships parade for July 29-August 2. A very good excuse to visit our neighbors to the north this summer.

Technically, St. Croix Island is in US waters, but the landing of the Acadians on these shores is truly an international historic event, and the two visiting centers on either side of the border are worth visiting and reflecting about, even if you are not of Acadian descent.

As we all know, Champlain soon thereafter led his own exploratory trips, still in search of a seaway to China. Yes, trade was the motor of exploration in those days. There were no agencies and grants to finance a research trip. It had to be self-paying in the long run. Champlain soon sailed up the St. Lawrence River in search of the Great Lakes, which he also did not find on his first attempt.

But what is important is that he persevered and eventually found and described the Great Lakes. He also founded the City of Quebec in 1608. What a guy! I see in him the real leader of the group, and were it not for his trip logs, we would not even know about the failed first attempt of a French settlement on a tiny island in the St. Croix River, and without his charts we would still be bickering about the border between Canada and the US in this neck of the woods.

Salute to the Acadians!

Info sources:

NOAA chart # 13398

H.P.Biggar (ed): The Works of Samuel de Champlain. Vol I, Toronto, 1922.

Roger Morris: Atlantic Seafaring. International Marine, 1992.

William Goetzmann/Glyndwr Williams: The Atlas of North American Exploration. Swanson Publ. LTD., 1992.

Farley Mowat: Westviking. McClelland & Stewart, 1965.

Stephen Hornsby (ed): Explanatory Maps of Saint Croix & Acadia. Canadian-American Center, University of Maine, 2004. (free hand-out)

© Reinhard Zollitsch

BACK TO TOP OF PAGE