AS A YOUNG BOY

(A story told for my American family as a record of a different time

or: you have come a long way, Reinhard)

Reinhard Zollitsch

(Finally written up in October 2013 – 60 years later)

Want to bike to Paris?

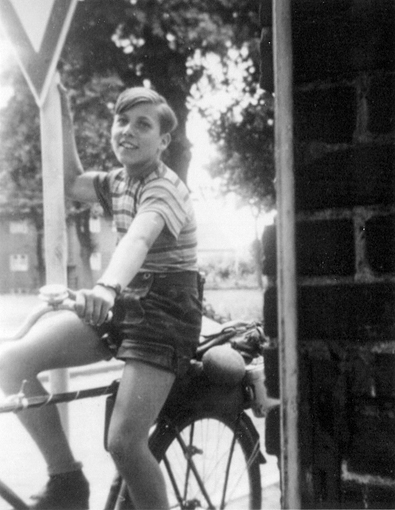

Watching the 2013 Tour de France, there were a couple of stages through the Ardenne and Vosges mountains and through towns that had a very familiar ring to my ear. And I thought to myself: you know those places, you have even biked through those towns and mountains – and then it all came back to me. I looked through my old photo albums, and there were my small black-and-white pictures of my first significant bike trip. It was a 2000 km (1250 miles) round trip through Germany, Belgium and France, from July 5 – 30, 1953. I was a mere fourteen years old, a very small, slender dude, but the very proud owner of a brand new, black, mail-order Stricker bike, for which I had worked and saved for several years.

Then one day at the end of the school year, the English teacher in our small north German town of Rendsburg, Herr Kindler, had asked eight of us kids, whether we would be interested in joining him on a bike trip from Rendsburg (60 miles north of Hamburg, Germany) to Paris, France and back. It should take about a month, i.e. our entire summer vacation. Since my best friend Manfred was invited also, I had no problem: I was in, and eager to use my new bike. To my parents and the parents of the other seven kids, it looked like a real educational school trip with a teacher in charge and a lot of historic sites to see and learn about. How little did they know!

We each loaded our bikes with whatever camping gear we could scrounge together; remember, it was only four years after the new Federal Republic of Germany ("West Germany") was founded (as well as its communist counterpart, "East Germany"). 1949 was a new beginning for all of us after ten very hard years, six war-years and four post-war "occupied" retaliatory years. I remember them only too well, having been born in the submarine harbor of Kiel in 1939. So it felt good doing something new and exciting, preferably away from our bombed-out cities. We would even see two new countries. It sounded real cool and like a perfect opportunity to check out my new bike.

From an older neighbor, Herr Hollweg, I got a World War I backpack and tarp, not thinking too much about how offensive the sight of that German army gear would be to the Belgian and French people we would meet on the streets. And when (in 1945) my grandmother's house, where we and other relatives were living at the time, was taken by the occupying forces for a year, I somehow ended up with an orange wool, American Army mummy sleeping bag. (By the way, all seven families in that 2-family home were asked to leave in 24 hours, taking only personal belongings.) My eating utensils for the trip were a WW II German army "Kochgeschirr" (tin pot with lid and handle), a knife/fork/spoon combination and a green, felt-covered flat-oval army water canteen/bottle. But my pride and joy was my ten-inch-long throwing knife, which all of us kids carried in a long leather sheath on our belts.

Early on July 5, 1953, our parents waved us off towards Hamburg on our first 100 km stage. Herr Kindler wanted the parents to see a proper start of the trip, even though we planned to take the train from Hamburg to the city of Hagen, at the outskirts of the Ruhr District, in order to make our long trip to Paris more doable from where we lived in northern Germany – almost on the Danish border. When we arrived in Hagen, I remember we were given an hour off to look around by ourselves. "But be back in one hour! We are leaving on time! Don't be late!"

But trouble did not start till next morning. Uwe was leading the group, when Manfred behind him had a flat tire. We all yelled for Uwe to stop, but he did not hear, or had decided to go ahead anyway and let us catch up to him. Well, after fixing the tire we waited for Uwe to show up, but he didn't. One biker was sent after him; still no Uwe nowhere, nohow. Fifteen or twenty minutes later we 7 boys and Herr Kindler decided to commence our trip, just as we had said we would. Poor Uwe! (But don't worry about him. He took a wrong turn on his way back to the group, eventually realized his predicament, and took the next train home. Trip over!) But all of us learned our lesson to stay together. (An aside: years later, when I took my college students for hikes or boat trips, I always jokingly informed them that a 10% loss was acceptable. I never lost a soul, but I do not think I would get away with even saying something like that nowadays, not even in jest.)

The real trip begins

Germany's new steel industry of the Ruhr River district was belching black smoke and soot from its many tall coal-fired chimneys into the air. We were glad to reach the Rhein (Rhine) River a tad south of Köln (Cologne).

At that point I first noticed that Herr Kindler was a history buff and wanted to see all the places where WWI and WWII battles or other significant war-connected events had taken place. I had no such interests, having just survived the bombing of Kiel and having seen the torched city of Hamburg. Near Bad Königswinter we pushed our bikes up the steep shores, not knowing what that would lead to. It was the famous hotel "Petersberg" where, we were informed, the constitution of the new Federal Republic of Germany was hammered out by the Allies and German representatives, especially the mayor of Cologne, Konrad Adenauer, West Germany's eventual first chancellor. What a place! We kids were in awe. (Note: At that time it was the seat of the "Allied High Commissioners", after 1949 the German "Bundesgästehaus", the official guesthouse of the German government in Bonn. The "Petersberg Agreement" was signed here, the first major step towards sovereignty of the newly founded Federal Republic of Germany.) There was a tall, decorative iron fence around the extensive park, but the gates were wide open. Then we heard Herr Kindler say: "OK, kids, this is it for the night. Make yourself inconspicuous under the tall spruce trees. See you in the morning." And we did. Manfred and I rolled up in our sleeping bags and tarps under a big Norway spruce and zoned out. We were tired, and this sounded like a very secure place, with fence and all. We must have munched on some stale bread and gnawed on a hunk of cheese, I think, because there was no cooking that night.

We crossed the mighty Rhine at Königswinter the next day and headed south to the small town of Remagen to see where the famous first Rhine crossing of the Allied forces in WW II took place. It did not mean much to me. The old railroad bridge was gone, except for two pillars and a museum, which we mercifully passed by.

We then left the Rhine and headed due west, biking upriver along the Ahr River from its confluence with the Rhine into the Eifel mountains and all the way into Belgium. The scenery was beautiful - vineyards on both sides and only small towns with slate-covered roofs. I enjoyed this stretch much more than anything we had done so far. At one point we stopped at a small waterfall/dam, swam, cooked yet another pot of spaghetti (or was it noodles this time?) and rolled up for the night, as always, making sure the open fire was doused properly.

Cooling off in the river Ahr (RZ way right in the water)

RZ tending the fire for our supper

At another place I remember looking at a house on the banks of the Ahr River: Adenauer's home ("big deal" for us 14-year-olds). Aachen (Aix au Chapelle) was a bit too far off our course, or we would have visited it also, I am sure. I remember gawking at the huge cathedral, from a later trip, and was surprised that Karl der Große/the Great (Charlemagne) was so small, the statue, that is. But the best part of our trip so far was biking on the famous car racetrack in the Eifel mountains, the Nürburgring, with the castle ruins towering on a hill in the distance.

Into Belgium: overnight in no-man's-land

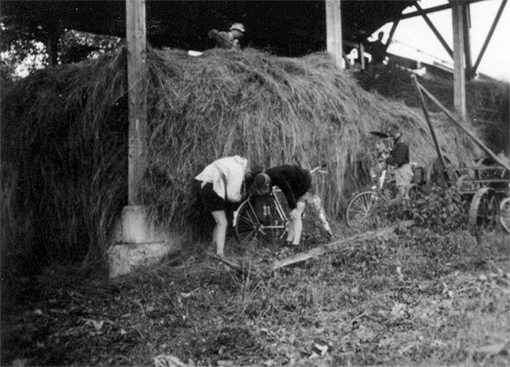

Our next overnight stop was a very special one. We were approaching the border to Belgium, checked out of Germany with our passports, and while we were biking towards the Belgian border control station in the next village, Herr Kindler got a gleam in his eye again and asked: "How would you guys like to spend the night in "no-man's-land", between Germany and Belgium, right here? See that hay shed? It's our "Villa Windy" for the night. Let's move in, boys!"

"Villa Windy" in no-man's land (RZ on the left)

"Gesagt, getan!" (No sooner said, than done.) We did not have to be urged twice. What a thought, spending the night in "Nowhere"! Fortunately for us, nobody noticed us or saw our bikes, which we had hidden behind the hay shed to be safe. Once in Belgium, Herr Kindler steered us along WW I battle lines, the Ardennes Mountains, behind and around the famous Maginot Line. This line of fortification was built by France around 1930, in hopes of keeping out a German invasion. Instead, the German invasion marched around it through neutral Belgium and Holland, as history will tell you, in our case, Herr Kindler. We saw Malmédy, Liège, Huy, Namur, Dinant, all the way to the Maas River, which we all remembered from a line in the Fallersleben poem, which became the German national anthem: "Von der Maas bis an die Memel, von der Etsch bis an den Belt". So this was the westernmost border depicted in that "song". Check!

Street showers (RZ in center)

Typical overnight stop

Into France on Bastille Day

We soon made it into France. It was Bastille Day, July 14th. Same story: we saw Sedan, another WWI battleground, saw Reims and finally the acres and acres of white crosses on the military cemeteries of Verdun. My maternal grandfather had died here in WW I, and so I thought I would pay my respects by finding his gravesite. But there was nobody who could help me, not even show me to the German segment of the cemetery. I felt very sad and deeply touched/depressed by seeing so many wasted human lives, knowing what grief each cross, each dead soldier, had caused for his family and friends. (In this case, my mother and siblings having to grow up without a father, and for us kids missing a grandfather.)

Verdun fortifications (RZ 2nd from left)

It also made me think of my direct family losses in WW II: one of my uncles was MIA on the eastern front (Russia); another, a medical doctor, was detained in Siberia for many years after the war; my father was badly wounded in Apeldoorn, Holland, became an American POW for a while, and also did not come home till months after the war had ended; and my other grandfather, the old sea captain, was pressed back into duty to pilot ships through the minefields in the approaches to the harbor of Kiel and the Kiel Canal. Not to mention all the harm German soldiers had caused in two world wars around this part of Europe and around the world. This was quite a burden for a little 14-year old, and still is for me today, as a matter of fact.

Even though we averaged about 100 kilometers/60 miles per day, Paris suddenly moved out of our reach. I did not mind much. What would we 14-year-olds do in Paris anyway? OK, there were the Eiffel Tower, the Louvre, Sacré Coeur, Montmartre, Notre Dame and the Arc de Triomphe, but I was getting tired of seeing more WWI and WWII sites and big cities. I wanted out of here. I was getting tired of eating nothing but pasta, hard, crusty baguettes and overripe, runny, smelly camembert (often with maggots in it, since we had no refrigeration). The cheap red wine was also not my favorite drink. So I was glad when Herr Kindler finally decided to head east after Reims. Seeing the cathedral there would have to do. So the new plan was to cross the Vosges mountains back to the Rhine, to Straßburg/Strasbourg, and from there back north, back to Cologne and home.

Brief rest along the Marne-Rhein Canal (RZ 3rd from right)

We followed the Marne-Rhein Canal to Luneville and Badonville and from there up to the top of the Donon mountain (1008 m – over 3000'), the highest peak in the northern part of the Vosges mountains. Finally back in real country, I thought to myself, as we raced downhill towards Schirmeck. "Wild Wulle Jönk", a slightly older and much bigger student, was passing me into a hairpin curve. I warned him of the danger, but by doing so missed applying my own brakes in time. We both did not make the curve and landed hard in the rocky ditch after somersaulting through the air. Fortunately for us, it was an inside curve, with the mountain on our side. (I don't want to think what would have happened if it had been an outside curve with the drop-off on our side.) Both of us got our breath knocked out, and both bikes needed to be straightened out at the local blacksmith shop in Schirmeck. The smith heated the frames and forks over his open coal fire and bent and hammered them straight again. Our bikes lost some paint in the process, but everything worked fine again afterwards. Wulle also had to see a doctor, who stitched up the gash in his forehead. I seemed OK, only shaken up. We did not talk about concussions in those days, but I have to admit that my memory of the rest of the trip is somewhat more clouded, hazy, and I had to ask my friend Manfred to jog my memory here and there.

Back into Germany

On top of Donon Mt. (RZ in center)

After all repairs were made, our trip went on, through the formerly German area known as Alsace-Lorraine to Straßburg/Strasbourg. At the little border town of Wissembourg/Weißenburg Herr Kindler decided to spend the remaining French money in the town's little "Gasthaus" (inn). We had a splendiferous meal with libations, after which the innkeeper allowed all eight of us to sack out on the floor in one corner of the inn. Images of the Flemish peasant painter Pieter Brueghel flashed through my mind, as we finally dozed off.

But come next morning, we were back in the saddle again, to Hagenau, Landau and Kaiserslautern eventually, "K-City" for you older army guys out there. Herr Kindler had a brother there, whom we visited. We finally took showers and had another great meal of sausages and real potatoes. No more pasta, please!

Herr Kindler in "K-City"

From there we followed the Nahe River to its confluence with the Rhine, where we took the Rhine ferry from Bingen to Rüdesheim. We then followed along the right banks of the Rhine, downriver, all the way to Koblenz, where we finally spent our first night in a real youth hostel. However, the youth hostel was in a castle on top of a steep mountain. Man, did we ever have to push hard to get there! We wondered whether it was really worth it. We could have found another cozy hay barn, some lonely hay stacks or big spruce trees to slip under. Once we got there, though, and caught our breath, the view was magnificent.

RZ and Manfred on Rhein ferry (Bingen-Rüdesheim)

Pushing uphill (RZ 3rd from right)

We eventually crossed the Rhine again at Bad Godesberg, and visited the quaint, old, little university town and birthplace of Beethoven: Bonn. In 1949, four years ago, Bonn became the new "temporary capital of the Federal Republic of Germany", West Germany. The government buildings looked truly temporary, very utilitarian, almost factory-like, nothing like the old Berlin, or other European capitals like London or Paris. (Not until 1991, after Germany's re-unification, did the capital move back to Berlin.)

We made it back to Köln/Cologne eventually, were in awe of the huge cathedral, but almost wept seeing the blown-out windows and pockmarked sandstone walls and pillars. Important was, though, that it had survived the bombings of the war and could be repaired, we all agreed. Next morning we took the train all the way back to our home town of Rendsburg. Our parents were delighted to see us back after 26 days on the road, literally. We smiled from ear to ear, proud of having finished the 2000 kilometer (1250 miles) bike trip, but knowing full well, that they would never hear all the details of that trip as I have described them now, 60 years later. I feel somehow relieved having done so.

Home at last

More Kindler trips

I took a couple of smaller trips with Herr Kindler the following years, even was promoted to group leader for his class of younger students. Each outing was always a competition: which group could hike/bike from point A to point B the fastest (with chart and compass only). We would have group wrestling matches and do some serious "Buchen-Biegen" (bending beech trees). We would climb young beech trees to the top, push off, and bend them to the ground, at which point we better let go and jump off, before we get catapulted back up into space. I later learned that Robert Frost, in his poem "Birches", describes a similar ritual: climbing birch trees "to get away from earth awhile (towards heaven), and then come back to it and begin over....One could do worse than be a swinger of birches."

Ours was much more violent. The palms of our hands were proof of it. (If any of you readers want to try that, make sure you wear heavy leather work gloves.) I can assure you, it is a great sensation falling back to earth when the tree cannot hold you any longer and bends over, and hopefully does not break, which would end in a nasty crash, hilarious for young kids, but not for members of the older generation. The consequences are even worse if you neglect to let go at the lowest point of your descent.

Learning English, the fun way

And yes, I also learned some English from Herr Kindler, proper British English that is. He was very well-read and had a very authentic sounding accent, unlike my grandfather, the old sea captain, who had learned his English only on boats and in harbors. It was very colorful and rough, which I, however, enjoyed immensely. Herr Kindler even had us sing English and American songs in class, while he plucked the tune on his guitar. Songs with swoopy melodies were our favorites. Our high school was all boys, all loud, boisterous, competitive, edgy and anti-establishment. (Girls went to a separate school.) "Oh my darling...Clementine" and "Way down upon the Suwannee River" were our favorites. We sang them with real gusto, till the teachers from the next door classrooms stopped our fun time.

I was later chosen to go to Lancing College, England (near Brighton on the Channel) for a term as an exchange student, which I would have enjoyed even more, if it hadn't been yet another rough all-boys school. To boot, it was a boarding school, where you were held captive on campus on a big hill till your "parents" visit you in their classic Rolls Royce, or you make the school team in any sport, which I did in track and field. And oh yeah, I eventually (1959) became an English major at the university of Kiel, my place of birth.

Last thoughts – "die Moral von der Geschicht"

But getting back to biking. In retrospect, I could have thought up a better itinerary for our bike trip, but this was the only trip offer around, and I badly wanted to try out my new bike. However, it was a memorable experience for the eight of us, which would include Herr Kindler. (Forget about poor Uwe! He blew it on day three!) Our teacher had fun also and remained a close friend of mine till he finally retired and passed away.

I was still riding my Stricker bike in college in Kiel, Germany, and on many weekend trips in northern Germany. And when I decided to come to the U.S. "for a year" (as a graduate assistant in 1962/63), I carefully oiled my bike and stored it in my parents' basement for later use. But when I came back several years later, it was gone, thrown out, "since you weren't using it anyway, and it was rusting and in the way". (Really? I still ride the Austrian-made Sears bike I bought in the U.S. in 1964, almost 50 years ago, and it still runs as good as new. Even the chrome rims and handlebars are spotless; only the tires, inner tubes, brake pads and cables had to be replaced periodically.)

Losing my old bike really hurt, especially since I had earned every penny for that bike. I was proud of it and had great memories with it. It had become an integral part of me; and now it was taken from me without my consent. I only hope someone picked it up before the trash truck came along and had as much fun with my Stricker bike as I always had. So on later visits to Germany I always had to borrow a neighbor's or friend's bike. My bike, by the way, was the only means of transportation I ever had. My family never owned a car, and during the 20 years I lived at home (I started college in 1959, in Kiel, Germany), no refrigerator, TV or washer and dryer, for that matter - a very different life from everybody these days, here in the U.S. and also in modern Germany.

End of story, but it is also the beginning of 50 years of my new life in Maine, with my wife, sweet Nancy, our family, our four children, our dogs, our home and my many boats...I am not complaining. As a matter of fact, I have made peace with my past and harsh childhood, and all's well now. No problem. Trust me. --- I could not change it anyway, so I accept it, live with it and make the best of it, which I feel I have done.

I clearly remember the first moment when a phrase coined by Thomas Jefferson in the "United States Declaration of Independence" hit me like a ton of bricks. It spoke of every person's "unalienable right...of Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness." I was more used to the more task-oriented German and French tripartite of "Einigkeit und Recht und Freiheit", or "liberté, égalité, fraternité". This American promise was a much more joyful thought and endeavor, namely, having the right to pursue happiness as a life's goal. It was a totally new concept for me. Life was no longer an "Aufgabe", a task to be solved, but lived and enjoyed. However, I knew all too well right from the beginning that it would not make life easier, and that there was no guarantee one would ever achieve happiness. But one could try and work towards it as a more personal, less intimidating, all-encompassing goal than the French and German tripartite cited above. And yes, I believe I am succeeding in this personal quest, even more so with each passing year.

Click here for a printable version of this article

************************

© Reinhard Zollitsch

BACK TO TOP OF PAGE