By Reinhard Zollitsch

March 2003

ENP WILDERNESS WATERWAY – ALLAGASH SOUTH

Ten years in the everglades…well, not really; not like the old timers Gregorio Lopez, Arthur Darwin or the notorious Ed Watson, and not even like the more recent Evergladians like Totch Brown or my Chokoloskee friend Thornton. I am even farther removed from those total immersion year-round dwellers of the Glades. I am but a snow bird from the cold northland of Maine, who, after watching his students for 30 years migrating south during Spring break, finally decided to join the fun in the sun, but in my own special way.

It was the Spring of 1992. I was getting tired of beating up on the younger fellows in our Spring whitewater canoe races and needed something new to dip my paddle into, something warm, for a change, with some navigational challenge, if possible.

Have paddle, will travel

So, what’s out there in the fun department for paddlers? First descents in China or Chile were definitely too extreme for me and financially totally out of reach. It had to be in the US and south where it is warm that time of year. The Rio Grande appealed to me, but only if there is enough water in it, which is not always the case. And then there were the bug, snake and gator infested Okefenokee swamp and the equally notorious Everglades, or were they?

After some background checks, the 100-mile-long tidal estuary of the Everglades National Park from Everglades City in the north to Flamingo in the south sounded more and more enticing. Winter and Spring, I also read, were the least buggy seasons down there, and coming from Maine, I thought, what are a few bugs. I can take it. It could not be much worse than May and June in our north woods, which I have survived on several longer trips down the St. John and Allagash and around Moosehead and the Rangeley Lakes.

After studying the three nautical NOAA charts (see appendix for numbers) I was hooked. 100 miles through tidal mangrove forests, like our local 100-mile semi wilderness trip down the Allagash River in Maine, sounded like the thing to do during Spring break. I began to think of this stretch as an “Allagash south” adventure. And no, I didn’t need a guide, nor did I need the sociability of a group, and I definitely did not want to pay a lot of money for the “pamper package” ($1500 and up for 10 days!). I had all my gear, including comfortable PFD and lightweight, user-friendly carbon fiber bent shaft paddle, and I enjoy planning my own trip from scratch. All I needed was a bare boat and drinking water for my four 2.5 gallon containers.

Click to download a full map (PDF format)

LOGISTICS

It took some planning to get a flight to Fort Myers with my two big duffels full of gear and food for 10 days, a ride to Everglades City, a bare boat from Sammy (ECBT, see appendix) and a car shuttle back from Flamingo. But all that is instantly forgotten when you push off in your boat towards your first destination, with compass and stop watch mounted right in front of you and charts secured in water-tight clear plastic chart holders.

It felt and smelled warm and so new among the mangrove islands for a fellow only used to a pine, spruce, birch and maple north woods landscape. I had worked out all major courses and distances for the entire trip in advance and had entered them on my charts in pencil. I was navigating as if I was in the island world of the Maine coast, only using the occasional numbered markers of the National Park Service to verify my whereabouts.

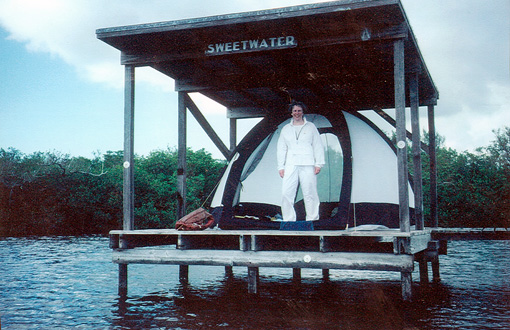

But I had underestimated the effect of the sun and heat when I thought 20-22 miles a day would be an easy jaunt for me, even though I had to push a two man boom-boom aluminum all by myself. I was surprisingly spent getting to Sweetwater the first day and Willy Willy the next. Sweetwater Chickee is a 10 by 12 foot wooden platform like a boat dock, about 30 feet off the mangrove shore in the water in a very secluded not easy to find spot in the park (no markers).

It was challenging to find, and I enjoyed that immensely. When darkness fell, fish were jumping madly all night, being chased by bigger fish, dolphins or gators. My flashlight bulb had broken in transport, and I realized I had no light other than my L.L. Bean candle lantern, a distinct oversight, which did not happen again.

Willy Willy to this day remains one of my favorite ground sites in the Park. It is way off the beaten path and not easy to find. But what a feeling, being there on an old Seminole/Calusa Indian shell heap under a large gumbo limbo tree, watching some big gators cruising by, checking you out. I decided to park my canoe smack dab in the gator slide to the water to get the message across that this little shell heap was MINE for the night.

At night I heard bull gators rumbling like a distant outboard motor, their love song - very eerie when you hear it for the first time, all alone, in a flimsy little tent as your only protection - but also magical and raw. I trusted my Timberline - my tent was my fortress - and tried not to worry too much, because I needed some sleep for tomorrow’s paddle.

After having traversed ten or more smaller and some quite large bays, all interconnected with often tiny streams like Alligator and Plate Creek, not much wider than 15 feet, I finally got to one of the larger rivers draining and re-supplying these large catch basins between the watery grassland, extending all the way to Lake Okeechobee, and the tidal estuary and eventually the Gulf of Mexico. The Broad River was big and ebbed very strongly, especially below 5 mile long Broad Lake.

"This is the life!" - Tiger Key

I spent a very buggy night two miles from the mouth of that river, just above the branch-off to “The Nightmare”, an 8.5-mile cross-over to the Harney River. What makes this stretch so scary is that it can only be run at high tide. If you get stuck or lost, you will have to wait for the next high tide, twelve hours or so later. There definitely is no way of portaging out over the myriad of mangrove roots and dense woods. I knew it was the ultimate challenge in the Park, and I had to do it, and do it alone.

Gateway to the Nightmare

I had carefully planned my departure in the morning on the incoming tide and did fine from marker #25 to #17, when I thought I had done it. The path was not much wider than my canoe in places. I was distinctly paddling though a tunnel in the woods. I hitched, pushed and poled over several root systems and always kept track of time and my course on the compass. Then at #17 I met Broad Creek, which looked like a real stream on my chart, and I was sure the rest would be a piece of cake. But suddenly the stream disappeared from under me. I was back in the mangroves. I was not ready for that; neither was my guidebook or map.

I was going in the right direction - due east - but should have gotten to #16 a long time ago, and on a proper little river or stream, not through the woods and over roots. Where could I have made a mistake, where could I have veered off course, I wondered. I stopped and replayed the last 30 minutes in my mind—no mistake on my part. Then I re-measured the distance on my nautical chart and recalculated my time: there it was. I had relied on the guidebook, and the guidebook had it wrong.

So I decided to go on for another 25 minutes; if I still did not see #16, I would have to turn around to the last known point, marker #17. Just as my stopwatch beeped, the “river” suddenly became a river again, and there was #16. Was I ever glad to see that little brown pole marker! That meant I had been on the right trail after all, but it looked everything but what I had expected and what was written up in the guidebook. This definitely was the longest hour in the glades for me ever, with some trepidation, I admit. But I still knew where I was, and I could have retraced my steps. That is all-important for traveling in the Everglades. Never get lost completely.

When I got to the Harney River, the tide was still running in hard, and I had a

relatively easy paddle all the way into big Tarpon Bay. I stopped for lunch at the place where it empties into Shark River, and waited for the tide to turn. Having the tide run with you is a great help on those big rivers like the Shark, Harney, Broad, Chatham and Lopez. But a headwind can make for very rough going also. Wind and tide will majorly affect your progress; so will the heat. But I made it fine to my little one-tent Shark River chickee.

At sunset that night, I heard a distant low hum getting closer, and I did not know at first what it was. But just in case, I secured my boat with two lines, retreated into my tent and zipped up. And not a minute too soon - the mosquitoes were out, by the millions. But next morning they were gone again. Whew!

Down into Oyster Bay and the Joe River in the early light and often calm conditions was fun, and the paddle to South Joe chickee, a very secluded and protected bight off the main drag, was delightful. One more day to Flamingo, crossing the southeast corner of the very large and often very windy Whitewater Bay into Tarpon Creek, Coot Bay and the Buttonwood Canal to the locks in Flamingo.

Flamingo is the main park entry point with lots of people, tour busses, even some motels and restaurants, and of course a little harbor with sunset cruises on a two-masted schooner with russet sails - how quaint. Definitely not the wilderness experience I had been enjoying on Sweetwater chickee or on the Willy Willy mound. I quickly carried my boat and gear around the locks, put in on the Florida Bay side and paddled and poled 10 more miles through the chalky shallow waters to East Cape Sable, the southwestern-most point of the Florida peninsula.

Top to bottom, 110 miles, in 6 days, 18.3 miles per day on average, at a speed of about 3 miles an hour. I felt pretty good and accomplished in these new surroundings, which always bring up new problems. Wind, tides, heat and bugs definitely have to be taken into account when you plan a trip through the Everglades. Even though the Wilderness Waterway from Everglades City to Flamingo is marked, so they say, it is not always obvious and still takes a lot of careful navigation if you do not want to get lost. That could happen very quickly and would not be a pretty picture.

At this point I felt sorely tempted to head back to Everglades City on the outside, island hopping along the Gulf coast. But my time was running short, I had not reserved the back country overnight sites and had arranged to be car shuttled back to Everglades City. So next day I reluctantly returned to the campground in Flamingo and waited for my ride.

For me the trip was over, even though I spent a couple more days in the 10,000 Island region just to kill time till my return to Fort Myers and Maine. But I had already planned next year’s trip: canoe the outside from the top of the 10,000 Island area, like from Royal Palm Hammock on Tamiami gator Highway #41 down the Black River and straight down to Cape Sable and into Flamingo. Maybe my family would want to come along, or go to Disney World while I paddled. They could pick me up at Flamingo and we could all go on together, by car that is, and check out the Keys, Hemingway’s Key West in particular.

ISLAND HOPPING ALONG THE GULF COAST

And that is exactly as my Spring break 1993 was spent. I enjoyed the outside at least as much as I did the backcountry. I always canoed outside of everything, of Pavilion Key, from there 5 miles straight across to New Turkey Key, around Seminole Point to the palms of Highland Beach, one of my favorite overnights of this trip. Then it got windy, and I had the darndest time getting around Shark Point into Ponce de Leon Bay and into the “Graveyard”, a back country camp site these days. But I had barely set up my tent, when a ranger boat pulled up and told me to pack my things as fast as possible.

Agave in full bloom on Pavilion Key

There was a storm coming, a big one, and they had orders to pick every camper off their sites. Very reluctantly I packed up. I knew he meant business when he rested his hands on his gun belt. Then we strapped the canoe onto his deck, threw in my packs, and off we flew across a totally churned up Ponce de Leon Bay, then Oyster and eventually Whitewater Bay, back to Flamingo. We hit the waves so hard, I thought I had suffered a spinal compression. I could hardly walk, so they dropped me off at the campground with a Ranger pick-up truck. I pitched my little Timberline in the same spot as last year.

The wind blew all night and got stronger by the hour. My little tent did nobly, though, slapping and banging, struggling to stay up. The surf on the beach was roaring till suddenly at around 4:00 a.m. it strangely quieted down, even though the wind continued to blow around 35-40 miles per hour. I felt unsettled and restless, and when I turned over and touched the tent floor beside me, it felt as if I was in a large waterbed. WATER! But it did not feel wet.

Flooded out at Flamingo - 1993 "Storm of the Century"

I unzipped my tent - the Gulf was flooding the campground. Half of it was already under water, including my tent. I got out gingerly, making sure I held up the bottom door zipper, zipped the tent shut again, pulled out the four corner pegs, grabbed hold of the two corner loops of the door side and slithered the tent, with all gear inside, over the water towards the only dry spot left in the entire huge campground, the bathhouse. There I packed everything back in my waterproof bags, took the tent down, which was quite a feat in this wind, and stowed all gear back in my boat as if I was going somewhere.

Soon the water had reached the bathhouse. So I tied my boat to two sturdy palm trees along the road and got back into my canoe to catch some more sleep. By sunrise I noticed that most campers had abandoned their sinking ships/tents. It looked as if a hurricane had gone through here. Piles of camping gear everywhere, but no people. I could not help anybody, because nobody was there.

They must have all gone to the Ranger station, the hotel, restaurant or motel.

I then decided to untie the lines and start paddling up the road to the motel where we had reservations. Little did I know that Nancy and the kids also had had the darndest time driving down from Orlando. Roads were flooded, gas pumps and phones were knocked out—this March 1993 storm turned out to be the “number three storm of the century” according to the national weather bureau, a storm that started in the Gulf and went all the way up the Atlantic seaboard, leaving in its wake major damage, numerous dead, and tons of snow in my neck of the woods in Maine.

The water came up to the motel threshold. We had no phone, electricity and other amenities usually found in a motel, but the manager let us stay. We cooked our meals on my camp-stove in our room, used flashlights and my candle lantern, and had a jolly pioneer-kind-of-a-time. But since water and wind damage is easily repaired, we decided to continue our trip as planned, with my rental canoe on our rental car across 100 miles of exposed bridges, causeways and keys to Key West. The car rocked a bit sideways with the boat on top, but all of us thought heavy thoughts, and we made it fine to the Blue Marlin in Key West.

LOOPING TO FLAMINGO

Since this trip was left somewhat unfinished, I had to come back another year and finish Cape Sable. I also wanted to see what damage Hurricane Andrew had done in the Everglades (in August 1992), since I had seen it just months before the storm. But car shuttles were out; they were too complicated and expensive. So I planned to paddle down to Flamingo and back again in ten or eleven days. As a matter of fact, I did it twice in the next couple of years (1995 and 1999).

A year after Hurricane Andrew

In both cases I paddled down to Flamingo in 4 days, stopping at Mormon Key, Highland Beach and Joe River on the way to Flamingo, then around Cape Sable and crisscross back to Everglades City. My 1999 trip was my favorite, even though the first four days were quite strenuous. I was eating up the miles and challenged myself to do most of it by memory and not by chart. I loved it and was in a good mood crossing Oyster Bay towards Joe River, when suddenly a thunderstorm appeared on the western sky.

I had almost made it to Joe River, but prudently stopped at a mangrove point opposite Mud Bay to put on my rain gear and let the lightning pass by. I was barely dressed and set in my boat, holding on to a tree root with my left hand and an overhanging branch with my right to keep my boat from being pushed into the mangroves, when a sudden wind gust of 50-60 miles per hour hit me. I held on for dear life like a green apple, which was not quite ready to be ripped off the tree. Waves formed instantly, and the wind was blowing the tops off horizontally.

Fortunately I had my stern and back to the wind, and the waves were deflected somewhat by the point I was hanging onto. But I had to hold on with all my strength, while at the same time keeping the boat from veering to either side, especially keeping it from hanging up under the mangrove trees on my left side and filling up or flipping. It was a bad situation, and in my mind I was preparing for plan B (get out, tie up the boat if you can and to heck with the gear) and plan C (get out and let go of the whole enchilada and hope to be picked up by somebody later and try to retrieve my gear).

Soon my boat was filling with water, from above and from waves jumping aboard. I had to bail to stay afloat. Fortunately my bailer was tied on beside my seat, so I could reach it easily and simply let go of it when my boat was getting out of control.

I must have hung there, with my upper arm muscles screaming with pain, for 45 plus minutes, but I could not let go completely and go on till about an hour or even more had passed. I was truly humbled by the forces of nature and felt fortunate to have something to hang onto. When I phoned home the next day from Flamingo, I learned that my dear wife was truly worried about me. Back home in Maine, Nancy had watched the national weather report on the TV Weather Channel that morning and heard the meteorologist (pointing to the Florida Everglades area) say: “If you know anyone down there who’s out on the water, tell them to get out of there fast. This storm means business.”

But after this stormy interlude the trip picked up nicely. I especially enjoyed going out around Sable Island and then all the way up Shark River into Tarpon Bay and on up tiny Avocado Creek to Cane Patch. This ground site is way up the Shark River Slough, the watery grassland, so beautifully and eloquently described by Marjorie Stoneham Douglas in her book The Everglades: The River of Grass (see appendix). Camp Lonesome was another of the most remote upriver overnight campsites like Willy Willy.

Fitting into the landscape at Northwest Cape

NANCY IN THE EVERGLADES

In 1996 my wife wanted to join me in the Glades, and I was delighted. Nancy and I had done lots of other canoe camping trips together, alone and with the kids. So I had a lovely seven day round trip planned for the two of us, with all my favorite haunts: Sunday Bay, Sweetwater, Plate Creek, South Lostman, New Turkey Key, Rabbit Key, and we felt very lucky to get all our first choices. (You have to make reservations in person, not more than 24 hours ahead.)

My favorite "chickee" - Nancy

The trip started out super, some wind, but not too much, warm, but not too hot. Sunday Bay had spectacular sunrises and sunsets, Sweetwater treated us to a vigorous rumbling chorus of bull gators, and Alligator and Plate Creek were filled with more gators than I had seen in all the previous years together. The big guardian of the creek blocked the exit to Alligator Bay and seemed very reluctant to move out of the way for us.

But since the current was drifting us inexorably towards him, it boiled down to a “heads or tail” call. Nancy chose “tails”, and the gator dropped under our boat at the very last minute. We held our breath, and I was ready for a low brace. (As if that would have helped!) Equally exciting were two dolphins charging through there at full speed, throwing a tremendous wake, bounding us into the mangroves. But the best wildlife was still to come.

When we arrived at Plate Creek Chickee, a 10 by 12 foot wooden platform with a roof over it, a six-foot diamond-backed rattlesnake had already taken up residence on the tiny mound attached to this chickee and was reluctant to leave. While we had our PB&J sandwiches in one corner, it finally decided it had had enough company and needed more space, slunk into the water and swam across the little bay to the opposite shore, which was all right by us.

But all night we heard little footsteps on the roof, our tent and on the wooden platform. A very active scene, which we could only hear but not see. (Mostly cotton rats I suppose.)

Then the winds came up from the northeast, and the trip took on a completely different character. We howled down Onion Key Bay and South Lostman’s River and decided not to go to Highland Beach, but rather hole up on the little island right at the mouth of the river. But then it got even worse: the temperature dropped overnight from the eighties down into the thirties!! and Nancy had trouble keeping warm, despite polypropylene long underwear, polar fleece sweater, Goretex suit, wool socks and hat, gloves, aluminum survival blanket and rain tarp.

She was definitely hypothermic. The wind was fierce and blew the water, so it seemed, all the way to Mexico. We were way off shore, me mostly pulling the boat across the shallows with Nancy bundled up in the bow. At Hog Key we had to stop, so I could hug some warmth back into her. Then we slugged on again as before to New Turkey. I used my marine radio, calling for help from any motorboat. But there was nobody else out there, and the National Park Service does not monitor any frequency, only the Coast Guard in Fort Myers (channel #16), and we were definitely out of reach.

The cold, wind and rain continued. Nancy recovered somewhat in the tent, in the sleeping bag with me beside her, and with food and hot drinks, but next morning we had to move on again, 11 miles to Rabbit Key. I soloed again, with Nancy bundled in the bow, being tossed back and forth in the waves, ending up black and blue all over her body. (She had a hard time convincing the doctor back home how she got to be so bruised all over.) That night our igloo tent almost totally collapsed, but it popped up again and did not tear.

The third day we experienced more of the same. Wind, cold and rain to boot, but I pushed as hard as I could back to Everglades City, where we knocked at the first trailer door we came to, were warmly received and eventually driven to a motel in town to warm up. It was either that or a hospital, and since there was none, we opted for the Captain’s Place.

FATHER AND DAUGHTER SOJOURN IN THE GLADES

Nancy made it fine through this ordeal, but needless to say is very cautious about going on another “Spring” wilderness canoe trip. But recently my oldest daughter Brenda (in her early thirties) thought the Everglades would be fun, at least to try it once, and this year’s Spring break was already our third trip together in the Glades. I especially like to see her relax from her stressful administrative job and enjoy what nature has to offer, from the significant, like alligators and a 7 foot crocodile at our put-in in Flamingo, and a pod of 17 manatees stampeding under our boat near Hog Key, down to the smallest buggy creatures and plants.

Daughter Brenda with crocodile, not alligator, at put-in in Flamingo

She catches scenes and moods and action on film, but also describes and draws them in her trip log. We both enjoy the chalky green expanse of the Gulf waters, the myriad of different birds and plant life, but especially the shiny, translucent green of the mangrove leaves in the early sunlight - a very soothing, calming sensory experience. Next moment we are on the lookout for rare sightings, like the elusive anhinga, a roseate spoonbill or a purple gallinule, or simply enjoy making our boat go.

Brenda is a fearless paddler, being a Maine whitewater raft guide on weekends, and does not mind bounding around in the often strong trade winds and choppy seas. She also is a quick learner in the navigation department and has her own charts and compass mounted on the bow deck in front of her. Most days she is the navigator. Since she can only take a week off from work, we do loops, or last year the whole enchilada from Flamingo back to Everglades City. After the father-daughter trip, I normally go for another loop by myself.

A daughter's view of Dad

THE RITE OF SPRING

Over the years, my Evergladian adventure has changed in character, from following the 100-mile-long official wilderness waterway from Everglades City to Flamingo, to doing various sized loops, to avoid costly car shuttles. I learned to combine the best of two worlds, camping in the mangrove forests, with island hopping along the Gulf coast.

Each year I also ventured more and more off the beaten path, searching for new routes to more remote sites, and tried to do as many stretches as possible from memory, like the “Old-timers” used to do (rather than with a NOAA chart in front of me). Traversing the Shark River Delta on ever new routes remains one of my favorite, most delightful navigational challenges.

"The Dude" in the Glades

While I continue to relish my usual solo solitude, I also greatly enjoy sharing the experience with family members and delight in watching them grow into the landscape, replacing their initial skepticism with relaxed joy. But please don’t ask me to go with or lead a group bigger than two. It would spoil the tranquil mood of the Glades. For me, losing myself in the Everglades and recharging my innermost self has become a veritable rite of Spring, which I look forward to all those cold and snowy, people-filled Winter months in Maine.

After 10 years in the Glades, or rather a bit over 100 days during Spring, I feel very much in tune with that part of Florida, at least during that season. And I cannot tell you how different it is from the rest of Florida, or from what most of my students are doing as fun in the sun.

Info:

Charts: NOAA #11430, #11432, #11433

Everglades National Park, 40001 State Road 9336, Homestead, FL 33034-6733

Tel: 305-242-7700; www.nps.gov/ever.

Everglades National Park Boat Tours (ENPBT), at Gulf Coast Ranger Station, Everglades City, 941-695-2591 (canoe rental)

Flamingo Lodge Marina & Outpost Resort, at end of Main Park Road, Flamingo, 305-253-2241 & 941-695-3101 (canoe, skiff and motor rental)

William G. Truesdell: A Guide to the Wilderness Waterway of the Everglades National Park. University of Miami Press, 1985.

Dennis Kalma: Boat and Canoe Camping in the Everglades Backcountry and Ten Thousand Island Region. Florida Flair Books, 1991.

Allan de Hart: Adventuring in Florida. The Sierra Club Travel Guide to the Sunshine State. Sierra Club Books, 1991.

Marjory Stoneman Douglas: The Everglades: River of Grass. 1947.

Totch Brown: Totch. A Life in the Everglades. University Press of Florida, 1993.

© Reinhard Zollitsch

BACK TO TOP OF PAGE