Across The Atlantic

By Reinhard Zollitsch

Across The Big Pond

“How would you like to sail across the Atlantic?” my wife greeted me excitedly at the door. “You would be leaving next week. I told them you would be interested.”

Nancy knew that I had grown up in a harbor town in Germany on one of the world’s busiest canals (the Kiel Canal, connecting the Baltic with the North Sea/Atlantic), and that I too, like my grandfather the sea captain, wanted to explore the oceans of the world and one day sail across the Atlantic or “Pond” as it is euphemistically known.

But I had almost forgotten that dream, with graduate school, new job, family, house - you know what I mean, the works, and had settled to sailing my little 22’ swing keel sailboat up and down the Maine coast, when suddenly, out of the blue, my wife got this phone call from a friend of mine in Camden, Maine wondering whether I would be interested in sailing a 45’ wooden schooner across the Atlantic to France, as mate and third watch captain.

I must have dropped some hints in our 13 years of married life, and she knew I had been messing about in boats, from rowing dinghies and shells to sailboats of all sizes. She knew about my sailing trip from Kiel, Germany to Scotland and the Shetland Islands on a 60-foot yawl. She also knew I had a sailor’s passport and had worked on a 1000 ton freighter on the North Sea and Baltic during college vacations and had arrived in this country on a coal freighter in Norfolk, Virginia as a penniless graduate student.

RZ with family before he left for France

But with two small kids and a third one on the way from Seoul, Korea (through international adoption), this was a big deal for her, and, as a matter of fact, is for anybody staying behind, and takes a lot of courage, more so than doing the actual sailing, I am convinced. Thanks Nancy for your strength, support and deep understanding!

We agreed to at least see the boat and meet the people I would be sailing with - no commitment, promise. (“We’re just going to look at the puppies...”)

Next day we drove down to Camden, and there she was: a traditional, two-masted, wooden schooner, 45 feet on deck with a 10 foot bowsprit, built in 1973 by Newbert and Wallace in Thomaston, Maine, to the plans of Pete Culler, who was thinking of the traditional Boston pilot schooners when he designed Fiddler’s Green for Ned Ackerman. Nancy and I looked at each other - words were not necessary - it was settled. By the way, the year was 1977 (May to be exact), and I had just celebrated my 38th birthday.

The boat and the crew

The schooner was well built from local oak and locust and had two sturdy spruce masts and booms with heavy cotton sails. Below was finished with natural locust wood with white trim; there were two wood stoves for heat and an ice chest for refrigeration and a bare minimum of necessary navigational equipment, i.e. short wave radio, VHF marine radio telephone (with a 30 mile range) and sextant - no Loran or radar, and of course no GPS (Global Positioning System), EPIRB (emergency transmitter), or satellite phone in the seventies!

The boat had a reliable 20-horse British Kelvin diesel with two large fuel tanks. It looked very traditional and was very functional and efficient, a bit on the sparse side in the electronics department. It also had a totally unprotected wheel box on the open afterdeck with a fishermen’s wheel, which worked like a tiller, not a car steering wheel. (If you turned the wheel to the right the boat would swing left, just as if you were pulling a tiller to starboard.)

The owner, Ned Ackerman, who commissioned Fiddler’s Green, wanted to sail her around the world, but in 1976, in the wake of the 1974 oil crisis, he had bigger ideas and had the same shipyard build him a 97 foot coastal freight carrying schooner, the John F. Leavitt, named after the Maritime author of “In the Wake of the Coasting Schooners”. In order to finance this project, Fiddler’s Green had to be sold and was picked up by a pharmacist couple from Paris, France, Vincent and Agnes, who sounded like very nice people.

In May of 1977 the two and Agnes’ brother Yves came over to Maine to look the boat over, find three more crew members, including a mate familiar with wood and canvas and hopefully some freighter experience for crossing the shipping lanes here and abroad - me - and shake the boat down before venturing out across “the pond”.

The skipper and wife were to take the first watch and were responsible for navigation (by sextant). Watch captain Yves, a competent sailor from the Bretagne, was in charge of motor and electronics and was willing to take on a young novice from Camden, 18-year-old Andrew, while I found a compatible watch mate in Portland, Kevin; I was responsible for wood and canvas as well as plotting our dead-reckoning. So we had three two-man watches, 4 hours at a time, with a 4-hour daily progression due to 2-hour lunch and dinner preparations with clean up.

Our first sail on May 31 was one big joy ride. Everybody, including the skipper, was grinning from ear to ear, trying to impress the other crewmembers how cool and competent they were. We managed to get all sails up including the topsail, even though none of us had ever sailed a schooner or fully understood each other all jabbering in different tongues. There was a distinct language barrier on board, due to the minimal English of the new owners and only my minimal French on the American crew side. “La voile” was a sail - I knew that.

But “la misaine” was the big sail on the fore mast? I did not know we had a mizzen on a schooner, and if we did, it should have been aft. And the helm threw us all, till I named it “Tilly” and treated it like a tiller. But I had to get used to steering by a direct-reading compass. The traditional compass, where you read your course off the top of the 360-degree compass card, had become second nature to me and was hard to undo in my mind. (As if “Tilly” was not confusing enough!)

We flew across Penobscot Bay to Pulpit Harbor and back, reaching 9 knots at times. The boat had potential, but we had a lot to learn. I could see lots of work projects ahead of us before we were ready to push off for good. But that night, the deck was filled with guests, friends and well-wishers for a significant lobster bake French style, “aux flambeaux”, and with lots of wine, champagne, French music and loud talking, way into the night under a splendid full moon.

Next morning was back to work: cleaning up, checking the standing rigging from the top of the mast to all deck fittings. We greased the masts with Vaseline so the sail hoops would slide easier, checked the running rigging, and I insisted on replacing the bowsprit footropes. I wanted to know that the ropes would hold me for sure if I was ever standing on them in the middle of the ocean, reefing and tying down the outer jib. I also measured for a canvas “dodger” all around the stern section, from the deck to the lifelines, to give the man at the helm some protection from the elements. Sailmaker Bohndell in Rockport had it done in two days.

The evening was filled with more wine and live music. A young fellow with a guitar insisted on singing us the song “Fiddler’s Green” which the Irish Rovers had made famous in the late sixties. It is about a place “where sailormen go if they don’t go to hell, where the weather is fair and the dolphins do play, and the cold coast of Greenland is far, far away...I’m taking a trip, mates; I’ll see you some day in Fiddler’s Green.”

Then it suddenly dawned on me that the fiddler was death and the fiddler’s green was the dance floor for the deceased sailors—and I suddenly became very quiet, went to my bunk and rolled up in my sleeping bag and zoned out.

To me it was not funny to name a boat after the “Grim Reaper”; it was almost like asking him or his servant the “Poltergeist” to appear, or at least challenge him with human hubris. I was distinctly uncomfortable with a name like “Davy Jones’ Locker” scrawled on my transom, but cool reasoning and logic finally prevailed and told me, it was only a name. Fate is what you make of your life, I kept telling myself.

New sails

After our next practice sail I noticed two small 2-inch tears at the end of the batten pockets near the leech of the sail. I pointed them out to Vincent and suggested we test the material by trying to rip the tears further, since they would have to be fixed anyway. And the little tears ripped and ripped and would not stop. We then stuck a knife at a different place in the sail, and the same thing happened. By then Vincent was furious about the sails, while I breathed a sigh of relief, feeling thankful that this whole thing happened now and not during the first storm out on the Atlantic.

With new sails, set for France

Not only the mainsail, but all four major sails were unusable. Something must have happened to them. After a few phone calls, we found out from Ned that the 4-year old sails had been treated by a sail maker in Massachusetts to prevent mildew, in a solution of (or including) kerosene and cuprinol. Nobody was quite sure about this anymore. Whatever solution they used, it obviously did chemically burn and weaken the cotton fibers. Rockport sail maker Bohndell confirmed our finding and agreed to make an entire new set of sails of 9 ounce dacron in 10 days, for $3500, which old and new owner would share.

Finally off into thick fog

By then June was almost gone. The sails were bent on again and fit perfectly. Thanks Bohndell! Provisions were bought, one brief practice sail was squeezed in, a last scrumptious going-away party was thrown on Curtis Island at the mouth of Camden Harbor, and next morning on June 24, 1977 we ghosted out into Penobscot Bay only to disappear in a fog bank.

We were finally off, what a relief. The last escort powerboat with Nancy aboard turned back, and it became very quiet on Fiddler’s Green. Only the diesel was helping us down the bay into the open Gulf of Maine against the incoming tide. We were bound for France - and there was no way of contacting anybody till we got there, which nobody wanted to think about.

We flew all sails including the topsail till about 8:00 PM when we took down the outer jib and topsail for the night, and a bit later even reefed the main when it started to breeze up. By then we were making great progress across the Bay of Fundy, 24 nautical miles during our 4 hour watch, and were approaching Cape Sable Island at the southernmost corner of Nova Scotia by noon of the following day. We then had a wonderful reach along the barely visible shores of Nova Scotia, but eventually were becalmed and used the diesel till 2:00 AM the next morning.

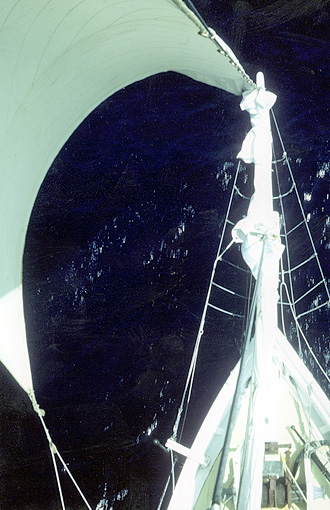

From the bowsprit

THE STORM

Kevin and I came on watch, and it suddenly started blowing from the northeast, a Nor’easter, and I knew we had to reef down, and asked the next watch, Skipper’s watch, to help us. He, however, was too groggy from his daily dose of red wine and was sure it would blow over; he refused to come on deck. “With 9 oz. dacron sails, this boat can take anything”, Bohndell had assured him.

One hour later, I again asked permission to reef, but was denied. By now I could barely keep the rails out of the water and decided to use the “German Fishermen reef” instead, as I learned it on the North Sea and Baltic: slightly overtighten the foresails, so each would backwind the next sail, taking power out of the sail, and slightly luff the main.

Kevin and I managed to sail the boat dry this way till 4:00 AM, when the new watch would have to come on deck and we could finally reef down properly. Again the skipper refused to reef because we were still so upright, and instead launched into a tirade about “Germans just don’t know how to sail ... the sheets are too tight ...we are not reefing...we don’t need you, you can go below...” and we did. Five minutes later all hell broke loose. We were sailing on our ear and the skipper called out the next watch, his brother-in-law and Andrew. (The off-watch would only come back on board if it were an all-hands call, but he had too much pride, and Kevin and I didn’t mind letting him eat his words and learn a humbling lesson at sea.)

They managed to take down the outer jib and tie it to the bowsprit and put two reefs in the two big mainsails. Soon thereafter even that was still too much for the boat, but instead of reefing the jib and the main down even further and taking the big foresail down, they took jib and main down, leaving the double reefed foresail.

It was a terrible night, the worst one of my life, and the wind steadily increased to 60 knots. Without any sails fore and aft we had lost all control of the boat. With only one sail in the middle of the boat, we also could not heave to nor could we run with the wind, the two major storm sailing techniques. It was a disaster. We would roll and corkscrew through the waves, rise into the sky and fall off with a bang. All pots and pans, everything in that boat was vibrating, clinking and banging; things would slide, fall and crash - the Poltergeist was on board for sure, and seemed to be having an outrageously noisy feast with all his friends, before he would take the boat down, as the sea lore goes. And every time the boat fell off a wave, the bell on the foredeck would ring - one eerie ring only. I had to suppress images of the real fiddler. He was playing all right, I clearly heard him, but it was not my song he was playing, I stubbornly maintained.

Kevin and I could not make any sail changes during our watch either, but could only try to keep solid water from crashing on deck with our minimal steering. I had sailed in force 11 winds before and also experienced that force on a freighter, but this was the first time I felt I was sailing in the ocean, surrounded by towering waves. Water was everywhere, and the wind was whipping the rain and spray into our faces. We had given up control and were at the mercy of the elements. I was truly thankful for this little boat to be able to stand up to the punishment of nature.

It blew between 50 and 60 knots all the next day too, and we were pounded into submission by the waves, the wind, the noise, the rain, the cold and lack of sleep. We shortened watches to one hour on deck for only one man, tied on with a sturdy harness. (The other would sit on the keel inside the hatch, fully dressed). We drifted to the southeast, 120 degrees on the compass, slowly but inevitably towards the infamous Sable Island and could not do a thing about it. I could not know then that our location was in the same area that the “perfect storm” occurred in October of 1991. All I knew was that we had to stay upright and get out of there fast, since there was not much room to drift.

Badly bruised but still afloat

During our 10:00 PM to 2:00 AM watch, our third 4-hour watch during that storm, the storm was finally beginning to blow itself out, and we even got some sleep after we were relieved. That morning the reefed main was up again, so was the big jib, and we were heading due east in dry clothes and with food. We all put on a smile and breathed a sigh of relief. Even the sun came out, and we enjoyed a great fast beam reach till sundown, which levered up a full moon on the opposite horizon. A wonderful image, and we in our little boat in the middle of a perfect circle.

On one hand it looked as if we were the center of the universe, on the other hand we looked like an insignificant speck in nowhere, surrounded by a perfectly circular horizon, which would keep coming with us like a halo, all the way across the Atlantic, and make it look as if we weren’t going anywhere.

Then suddenly we came upon a huge Russian spy ship anchored just far enough off shore to be considered in international waters. At first the ship seemed to be deserted, when suddenly lots of heads popped up over the railing, staring at our little sailboat, even waving their arms, maybe remembering the storm and wondering how we had made it through. Even spies are sailors at heart, I thought to myself warmly.

With Yves’ help I persuaded the skipper to give each watch captain the authority to call for a reef, and night sailing would only be done with reduced sail, i.e. definitely not with topsail and outer jib, since it was not on a furling gear but had to be taken down by getting out on the bowsprit; not a very safe thing to do in the dark of night. He reluctantly gave in but reversed his decision many times on our trip across the Atlantic.

Foggy Grand Banks and shipboard routine

On our seventh day out we approached the Grand Banks (off Newfoundland) and inevitably hit fog, which lay thick over the water but allowed some sun to filter through overhead, a strange sensation. We were barreling along with all sails at 7 knots, relying on our tiny metal radar reflector and mast strobe light to be seen by other boats. We heard some distant fishing boats, but made it through the fleet fine to Cape Race, the SE corner of Newfoundland, our jump-off point to Land’s End, England. We had covered 135 nautical miles in the last 24 hours, our farthest so far, and even got a sun fix at noon, just when we needed it.

1851 more (nautical) miles to the next shore! - a formidable and somewhat scary task, but our team was working together somewhat better, even though we hardly saw each other except at meal times. Kevin and I had made each other co-responsible for the safety of the other, and we worked well together and knew what we were doing. Yves was a very competent sailor and also very patient with the newcomer Andrew, who did admirably well, was cheerful and learned very quickly, especially how to stay out of trouble.

Vincent and Agnes on the other hand were trouble all around and turned the trip into an unpleasant experience. First, they had major marital problems, which were exacerbated by any tense moment on board. Their conversations mostly ended in a shouting, even pushing match, most noticeably during the dog-watch from midnight to 4:00 AM.

Secondly, their tension, stress and anger were vented towards the other crew members, especially the other non-family watch captain, me. (That I had grown up in Germany did not help much either.) Frankly, there were many moments where I would have gladly stepped off the boat, rather than take the crap or act as a peace-maker in quarrels between them or with other members of the crew.

Food was another bone of contention. We were all cooking and cleaning up on a preset schedule (2 hours of the lunch and supper watch), but Agnes would set out the food for each meal. Typical lunches were corned beef or tuna on either potatoes, rice or spaghetti, for 25 long cold days at sea. No real vegetables to speak of, since in French nomenclature, potatoes are vegetables.

Supper mostly consisted of soup, regular Campbell’s soup, 3 cans for 6 people, following serving instructions (mixed with water), with dry crackers and a hunk of ripe cheese, and occasionally an apple for dessert. Lots of cans and alcoholic beverages were locked away in the bilge “for emergencies”, like being shipwrecked on an island!? The emergencies never happened, and the supplies stayed locked till we landed in St. Malo, France, with Agnes as guard dog even sleeping in the saloon, fearing we would snatch food during our off watches.

1000-mile celebration

On our tenth day out, though, I have to admit, we celebrated our 1000-mile marker with a real feast compared to our normal fare. Agnes dug deep into the bilge and came up with canned turkey, peas, creamed corn and a canned fruit dessert, and Vincent offered everybody one glass of sherry. Now that was a very special and unique occasion on this boat! But I was still glad I had brought my vitamin pills.

Another thing was the cold. We had left Maine on June 24 and always stayed north of the shipping lanes. I am telling you, it was cold. How cold? I lived in thermals, wool socks and sweater, extra jacket and oilskins for almost the entire trip. I find the following embarrassing note in my trip log on the 13th day of our trip: “clean socks and underpants, combed hair, brushed teeth with toothpaste, all for the first time”. It was just too cold to bare your skin, and we were simply too tired and cold to function fully.

RZ at the helm

In 1977, we had no understanding of hypothermia. We were either shivering on deck or warming up again in our sleeping bag with minimal socializing during food intake time. The first couple of days beyond Newfoundland were extremely cold. The water looked bluish-green and very thin - we were crossing the Labrador iceberg zone, acording to my pilot charts, and had to be on constant lookout.

Our second storm

The night of our 1000-mile celebration was lit up with heat lightning, frighteningly close, with the wind suddenly gusting up to 50 knots and with seas coming from all directions. Agnes in particular had a hard time keeping from jibing the boat, and when she did that one too many times, the metal “misaine” (foremast) peak fitting broke, and sail and gaff came crashing down on deck. She adamantly maintained that it was not her fault, that we had weakened the fitting and it could have happened to any of us!

But the real storm, our second, did not hit till the next day. This time we were ready with triple reefed main, single reefed big jib and no outer jib, and “la misaine” was already down, thanks to Agnes. The waves were gigantic but regular and predictable, unlike in our first storm, which was total confusion.

This time we were sliding down the backs of the huge waves at frightening speeds. At the end of each glide we had to watch out not to dig into the back of the previous wave, but rather turn slightly to windward till the crest would catch up with us and rumble under our hull. It was very intense. The boat would track like an express train, and Kevin and I took turns at the helm every hour. Our concentration was shot after that.

Next day Kevin and I managed to replace the broken mast fitting with a wrapped sturdy steel strop shackled around the top of the mast. It worked and held for the rest of the trip. But a sonic boom that night made us think the gaff had crashed down on deck again or something had blown up in the rear hatch. We rushed on deck and searched all around with flashlights, but nothing had happened.

From the fore mast

I remembered the supersonic British/French Concorde had just started service across the Atlantic the year before; it could have been them or some military plane. I was quite familiar with that sound having grown up in post-war Germany. But I am telling you, sonic booms are always a scary thing at night on a small boat in the middle of the Atlantic.

Hitting the Gulfstream

On day 14 it finally got a bit warmer. We must have entered the Gulf Stream, because suddenly there were gannets overhead, and porpoises and dolphins were riding our bow wave, racing beside us or even doing aerials. It was fascinating hearing their “tsiu, tsiu” from the forepeak below deck. But my new socks from yesterday got soaked while taking pictures, a real bummer.

Our big genoa pulling hard

From that point on, time seemed to crawl by at a snail’s pace. The routine on board, including the food, became very repetitive, monotonous, especially when nobody could find a nice word to say to the other crew members. Agnes in particular got totally unhinged and maligned everybody and slashed out at everything. I only had fun when she was sleeping or out of sight with her mouth shut. It was that bad. Kevin, Yves and I got along fine, though. Andrew was too young and inexperienced to figure in this equation, but he was certainly a nice, cheerful, eager learner. I definitely stopped counting the miles we had already sailed, but rather looked ahead at the distances to Ireland, The Scilly Isles off England and St. Malo, France, the distances yet to be sailed.

The weather did not help lift our spirits either. The wind shifted to the southeast instead of coming from the west and was too light to move us along in any direction. So Vincent grumblingly started the engine, then sailed a bit, only to start the diesel again. We used up half our fuel in the middle of the Atlantic, even started our second tank, which we had wanted to save for the Channel crossing where we might really need it, and for getting into St. Malo.

The Isles of Scilly and Land’s End, England

The days dragged on till we had Ireland abeam on the 22nd day of our trip. 120 more miles to The Isles of Scilly, off Land’s End, the southwest tip of England! On July 16, on day 23, I made out the two flashes every 15 seconds of Bishop Rock. We are getting there after all, I thought to myself. I had read about this area being one of the most intimidating places around, and I was willing to give the Scilly Isles a wide berth.

I knew the only 7-masted schooner ever built, the Thomas W. Lawson from Quincy, Massachusetts, foundered here in 1908 in a storm, and sank, taking fifteen crew members with her - and we were headed right through that boulder field, between Round Island and Seven Rocks. When I mentioned this to Vincent, he only grinned at me fiendishly.

On we went past Wolf Rock, which had recently claimed a huge tanker, and straight across the Channel. This was the hairiest sailing I had ever done in my life. It was like crossing a six lane super highway with everybody going full speed without any brakes. Fortunately we had daylight and plenty of wind, actually much too much wind in the choppy tidal maelstrom.

Crossing the Channel in rough weather

At one point a Polish freighter from Gdynia changed course just to get a better look at us. I knew there would be trouble when the wind would hit the deck load of containers from the other side. The freighter would change course drastically and would be upon us before he could get his bow back under control. So I suggested running away on a fast beam reach, and it was still a close call.

Then there was a huge Japanese tanker way off on the horizon, and everybody thought we could easily cross over before he got there. I insisted we let him pass in front of us, even if that meant changing our course slightly. Sailboats do not have the right-of-way crossing shipping lanes, and tankers cannot and will not change course or slow down, because they follow prescribed courses. So we grudgingly passed close astern of the big tanker and were fine.

I was thankful that Yves took over the navigation into St. Malo Bay. This is a very formidable coast, especially at night, with lots of headlands and lighthouses, rocks and ledges, and legendary tides. St. Malo has tides that rival those of the Bay of Fundy, Canada. I hear St. Malo even has a huge tide-driven power generating station.

At St. Malo at last

On July 18, our 25th day of the trip, we motored into the inner non-tidal St. Malo harbor basin. It was 7:00 AM local time. We tied up against the stone promenade, along with a bevy of super racing boats which had just finished the Cowes, England to Dinard, France race and who were now getting ready for the 1977 Whitbread Race Around the World. Our boat looked completely out of place, like a ghost from a different time. We were dwarfed by the English yacht Great Britain II moored beside us and the French Rothchild super yacht Gitana, but I told myself, this is it, we had done it.

WE HAD ARRIVED!, but there was nobody there to greet us. Agnes and Vincent did some paperwork, then ran off to meet friends and were gone till after lunch. No cheers, no toast, no thank-yous for having sailed the boat across the Atlantic for free. This moment was a monumental letdown, the biggest one in my life so far. Here I was in the city of Jacques Cartier, one of the early explorers of the new world, whom I admired, and I did not feel a thing. It was a total washout. It was definitely not what I had dreamed it would be.

The moment of elation had turned into a moment of relief. I was numbed by our trip, and was now gawked at by thousands of tourists who looked at us as if we were caged animals in a zoo or a painting in a museum. Nobody knew we had just sailed 25 days across the Atlantic, 2652 nautical miles to be exact, and barely made it at that.

After a perfunctory good-bye dinner in some restaurant, I packed my duffel the next morning, boarded the express train, “Le Rapide”, to Paris and could not wait to get back to my family and friends in Maine. I was sad, though, to leave that beautiful wooden Maine-built schooner in the hands of the new owners, who sailed her for another 20-some years in the Gulf of St. Malo/Brittany area, till the boat ended up on the rocks, dragging anchor, in the Isles of Chausey off St. Malo and sank.

All aboard were saved. I have not been able to find out the exact date. I also never heard from or saw any of the crew again. So ends the somber story of the schooner “FIDDLER’S GREEN”.

PS:

Ned Ackerman’s 97’ schooner John F. Leavitt went down in a storm on her maiden voyage from Quincy, Massachusetts to Haiti in December 1979, 260 miles off Long Island, NY with a load of lumber. All crewmembers were rescued by Coast Guard helicopter.

PPS - December, 2002:

25 years after the Fiddler’s Green trans-Atlantic trip, I finally decided to write up this story and to unburden my mind. I also hated to say anything negative about other people, but when I heard this boat had sunk and its life was over, someone had to write the story of how this proud Maine schooner left the shores of New England. After 25 years I also hope the members of the crew will forgive me for my criticism. I for my part decided to stay away from traveling with groups and go instead with my family or solo, like my many solo canoe trips along the New England and Canadian Maritimes coastlines (see my articles in MESSING ABOUT IN BOATS, ATLANTIC COASTAL KAYAKER, KANAWA and PADDLER MAGAZINE).

Technical and other information:

FIDDLER’S GREEN, already registered in St. Malo, France, in May 1977

Built by Newbert and Wallace, Thomaston, ME; launched 1973

Naval architect: Pete Culler, Hyannis, MA

Type: 2-masted topsail pilot schooner, 45 foot on deck, 10 foot bowsprit

Built with local oak and locust

20 HP British Kelvin diesel

Wooden dinghy over stern

Short wave radio to get exact Greenwich time signal

Sextant, VHF marine telephone (30-mile range), mast strobe light and radar reflector, life raft with strobe light

NOAA nautical charts #5101 Gnomonic Plotting Chart, North Atlantic, # 109 Gulf of Maine to Straits of Belle Isle

NOAA Pilot Chart of the North Atlantic Ocean - for June/July, 1977 (for statistical info on wind direction and speed, currents, ice, etc. - an absolute must for anybody venturing across “The Pond”)

The Irish Rovers: On the Shores of Americay. MCA Records, 1971

(There was no way of contacting the outside world during our crossing.)

© Reinhard Zollitsch

BACK TO TOP OF PAGE