Rounding the Gaspé

1000 miles solo by sea canoe

Part I: Whitehall, NY - Québec, Canada (350 mi - 560 km)

August 1999

By Reinhard Zollitsch

Going 1000 miles one stroke at a time

The Gaspé peninsula in the Gulf of Saint Lawrence has always been dear to my heart. It was here that I took my first camping trip after arriving in the new world from Germany and fell in love with a bright young girl from Maine. 36 years later, Nancy is still by my side, but at 60 I needed to refresh my memory of the splendid, bold landscape of the Gaspé, but this time from the sea.

I had done several long open-water trips in my 17’ Verlen Kruger sea-canoe, along the Atlantic coast from Boston to Machias, Maine (see MAIB, April 1, 1998), around all big lakes in New England and New Brunswick (see April 15, 1999), but the St. Lawrence, the Gulf and Chaleur Bay would be a new and formidable challenge for any small boater, especially solo and unassisted. Furthermore, I had always wanted to canoe 1000 miles, and after some jostling of options, I finally came up with a perfect plan for the summer of the last year of the millennium.

I would start at the southernmost tip of Lake Champlain, at Whitehall, NY, check out that last and biggest of our New England lakes and continue due North down the Richelieu River into the St. Lawrence and on to Québec, as Samuel de Champlain had done in 1609 on his way back from Fort Ticonderoga. No, he did not find a route to the Atlantic (the Hudson-Champlain canal was not built yet, nor did he find the real Great Lakes, not on this trip anyway, despite New York’s and Vermont’s repeated claim to Great Lakes fame), but he must have found an awesome, big and beautiful lake.

In late May school was out and “Old Teach” was free to pack his gear for the first stage of his trip, the 350 miles to Québec. It happened to be our 35th wedding anniversary, when Nancy and I drove to the put-in in Whitehall, and spent a wonderful time including farewell dinner in the historic Finch and Chubb Inn right next to Lock 12, the last lock of the Hudson-Champlain canal.

Put-in at Lock #12 Marina, Whitehall, NY

With all gear for 2 weeks safely stowed and tied down in waterproof bags, charts, compass and stop-watch mounted or secured in front of me, with spray skirt on, I headed due North, ~20’ on the compass, wondering, thinking, and trying to anticipate what lay ahead. Thinking about the entire trip, 1000 miles solo in a sea-canoe on open water, which would get worse as the trip progressed, was too daunting and intimidating. So I limited my concern to the first 4 miles, the first hour, and so on, just as Bob did in the movie “What about Bob?” Break it down into “babysteps”, one step or one mile or just the next point or headland at a time. And it worked. Thanks, Bob.

My goal for the day is 25 miles, so I had carefully studied the maps and charts to see where that would be and where I could stop for the night and pitch my little Timberline tent. Since I was totally self-contained, (I only needed to replenish my two 3-gal water tanks twice), I avoided towns, marinas, campgrounds and the like, except for an occasional phone call home to report my progress and whereabouts.

I am off – Lake Champlain

The first night saw me camped in a spot where I could see Fort Ticonderoga out my front door. My green tent and green tarp over my boat made me practically invisible on that tiny patch of green grass.

I was truly impressed with the beauty and remoteness of the western shore of Lake Champlain. Mountains right down to the water’s edge, a steep granite shoreline with cedars clinging to every cleft in the rocks and from each point the magnificent views of the distant mountains of the Lake Placid area and of course across the lake on the Vermont side. After the only bridge across the lake at Crown Point, the lake gets big, big and windy, very windy in places.

But I danced or slugged my way north through The Narrows with impressive Split Rock Mountain on my left, around Split Rock and Hatch Point, still adhering to my pre-set 25 miles a day pace all the way up to Valcour Island, just south of Plattsburg. And what a lovely surprise and respite this was. I found a wonderfully protected crescent beach on the western shore with huge oak trees at its rim for shade. Two sailboats stopped in around supper-time, otherwise I had the beach to myself, as most of my overnight spots.

A big fog bank over the open lake the next day made me head prudently back across towards Plattsburg and Bluff Head rather than cutting across to Crab Island and on to Cumberland Head. The landscape was changing abruptly at this point. The mountains were distant memories and the shoreline was flattening out, allowing more and more summer homes to crowd right down to the water’s edge.

Down the Richelieu River and Chambly Canal, Canada

One more night at the mouth of the Chazy river, and I was in Canada, past Fort Montgomery, the customs station and down the Richelieu River with flocks of noisy Canada geese overhead. The river was wide, with low banks covered with willow and poplar and tall marsh grasses extending far into the river. A thin line of smallish houses on both banks with flat farmland dropping off behind it. At times I felt the river itself was the highest point around, which of course is impossible, but this was without a doubt one big floodplane, only interrupted by one mountain range at Mont St. Hilaire, visible for miles.

North with the geese

I spent 3 nights on the banks of the 70-mile stretch of the Richelieu River, and what an exciting time it was. It was a weekend, and everybody was out on the water or was jogging, hiking, biking, roller-blading, visiting or having a restful time on its banks. On the water was Memorial Day mayhem. I have never seen so many boats go that fast in such a restricted space in so many different directions as here on that weekend.

Under the Beloeil bridge just upstream of Mont St. Hilaire, where the current was running real hard through the only navigable left span of the bridge, I met two ocean racing powerboats trying to pass each other with wide open throttle. One of the boats was decked out as a Bat-Mobile with a driver in a batman costume. The other boat was an evil black hull with a matching driver. (I am not making this up, folks. I am not suffering from sunstroke.)

There were more ocean racers out that day, even catamarans, all going almost as fast as they could go, and as far as I could tell, nobody got hurt, and all had a good, i.e. wild and lawless time. It reminded me of the Walpurgisnacht scene in Goethe’s Faust, devilishly wild and out of control. And on Monday morning it was all over, maybe even quieter. This also was the time that I noticed that the Canadians do not observe Memorial Day, and this Monday and weekend for the same reason were just normal weekends.

Anyway, I was glad to get on with my trip. My nautical charts for the Richelieu were great, though expensive, but very necessary. It was a low-water spring, and the stretch of “The Thousand Rocks” would have been too hard on a fully loaded canoe, not to mention the two dams, which would have necessitated portages anyway. So I opted to join a couple of sailors with mast down and motor cruisers down the 12.5 mi Chambly canal.

In lock #9 of the Chambly Canal

The 9 locks and low-low swing bridges were quite an adventure, but in the end much easier than I had anticipated. I had to hold on to a rope while being lowered about 10’ each time. The tenth lock at St. Ours was even easier since it had a floating dock inside the locks to tie up to or hold on to in my case. The lock fee is figured out on the length of the boats, regardless of how “fat” you are. For my 17’ boat that came to a total of $34 Canadian, definitely worth it for me.

The mighty St Lawrence River, Canada

From St. Ours the Richelieu is tidal for the last 10 or so miles to Sorel where it joins the mighty St. Lawrence. And it is a mighty river, and I admit I underestimated it, at least I did so on the 130-mile stretch from here to Québec. I thought I could just hang a right in Sorel, go basically NE and hang on the right shore till I see the dual bridges at Québec. How difficult can that be? I was so cocky, or rather uninformed and maybe also a bit cheap to think I could save $100 for the 4 nautical charts. But I soon paid for it.

The islands and shallows from Sorel into Lac St. Pierre are so confusing and unnerving that I ended up so close to the shipping lanes that I could read the names of the ships on their bow. I remember seeing one with an icebreaker bow, orange-red hull, and I knew from my sailing in the Baltic and North Sea that this was a Danish ship of the DAN lines. I was distinctly too close, especially when I encountered their bow wave and wake breaking in the shallower water I was in.

As always in situations like that, the situation is exacerbated by a 20 knot NE wind blowing against a strong ebb tide forcing its way through the restrictive islands, and a steady rain. I had to get out of there fast, and I finally found a short-cut through those endlessly long thin islands to the mouth of the St François river where I holed up for the night.

After a wet night, heavy fog greeted me the next day. After running my course for two hours towards the bridge at Trois Rivieres, darting in and out around the myriads of salmon weirs, set up in the shallow water extending about 3 miles into the lake, I was stopped by a navy airboat. “You have to go back where you came from.” “NON!” I could not possibly find my way back, because I did not want to. “You go across the lake to the other shore.” 10 miles in this weather with the wind still in the NE: “NON!” “Then you get out of your boat. We are shooting here.” I could clearly hear that.

With my minimal French knowledge I finally figured out that I had drifted into a 3mi X 2mi military target practice range. My suggestion was, that they take a coffee break and let me paddle through. It would only be 45 minutes. He did not go for that; he did not even ask his superior but ordered me out of my boat, told me to put my bowline over his bow cleat and hold on well, because here we go. And believe me, we went.

At first one mile into the lake with the waves running parallel to our course. Great, I thought, no problem. Thank you Verlen, for designing such a stable boat and thanks for laying it up in Kevlar because we were hitting the air boat. Then a 90-degree course change straight into the wind and waves, which were again whipped up by the tidal flow.

The bow went under and water rushed over the cockpit cover. I was glad I had a semi-decked canoe with a spray skirt, but I did not close the cockpit hole where I normally sit in. There was no way to close it, and my driver was not going to stop for anything trivial like that. Water splashed into the boat till the stern was completely in the water. The boat began to roll from side to side. She is going to roll over and swamp, I thought. I have to bail. I tried my best French. “Trop d’eau dans mon bateau. Lentement! Arretez! Au secours!”

By then we had gotten to the firing platform where I jumped out, bailed furiously and surveyed the damage and was about to quietly sneak off towards Trois Rivieres when I was firmly informed that the trip was not over yet. So here we went again. But this time into very shallow water, and so that the airboat did not suck down or touch bottom, he opened his throttle wide and we flew across the grassland.

My canoe with all its gear was furiously banging against the sides of the mothership, trading paint, rolling wildly, but catching itself each time.

I wondered whether Verlen had put a counter-plate on the inside of the bow rope fitting to which I tied the bow line. It held, we stopped, I jumped into the shallow water, bailed, got in, and paddled off without looking back.

On to Québec City

Then finally there was the huge Trois Rivieres bridge. I was wet, shivering and hungry. The wind increased to NE 25 mph. It was all white around me. Then I saw my overnight spot. It was perfect: the base of the huge powerline tower with its massive concrete feet that would give perfect wind protection for my little tent. There was a causeway out to it, some grass, a rocky beach to take-out and put-in the boat and deep water all around. It rained all night, but the essential gear was dry. My small propane stove did overtime.

Next day another 25 miles with lots of freighters steaming by. Every bend in the river looks like a big lake. To cover the riverbend from Platon Point to St. Antoine de Tilly took me 3 hrs, but then it was 12 miles. It was hard to adjust to such a large-scale river coming from New England where the Penobscot, Kennebec or Connecticut are considered large. After 9 hrs in the boat with minimal breaks (30 min. total for the day), I was totally spent, my “tank was on empty” and I was looking for that flip switch the old VW beetles had to switch to the reserve tank.

I could not find it, and beached my boat a good 1/3 of a mile off shore on the hard shoaling shelf of the river somewhere around St. Antoine de Tilly. I got caught at low tide at a long stretch of the river where the deep water was on the opposite shore. PORTAGE, then collapse and slowly pick yourself up again with coffee, cocoa or stale water by now tasting like the plastic bag it is stored in.

This was my last night on the river before Québec, and I was to phone home to arrange for a pick-up at the ferry dock at Lévis across from downtown Québec. That was just too bad, but I figured Nancy would figure things out anyway and be there at the usual HIgh-noon pick-up. Then Jean-Michel, a young boy on a mountain bike showed up at my tent site out of nowhere, we talked and I asked him to phone Nancy with a short message, which he did. Thanks, Jean-Michel.

The end of this first leg of my trip was perfect. Great weather, the tide turning at the Cartier/La Porte bridges, so I was nicely carried the last 12 miles to the ferry dock. But the wind sprang up again from the NE against the tide, which by now was running madly through the restricted area between Québec proper and Lévis to the south. The last mile I was dancing and thankful for the tiny beach just before the formidable ferry dock piers which jutted even farther into the river, causing the tide to rip and reverberate off the sheer sides.

I had barely lugged my boat and gear to the roadside beside the Ferry terminal when I heard the familiar horn of my VW Golf and Nancy’s friendly voice. I HAD MADE IT, finished the first leg of my trip. 350 miles in 13 days, i.e. 27 miles per day on average. And to make my duplication of the 1609 Champlain trip perfect, Nancy had booked a room at that big place across the river where Champlain’s fort used to be and from where he established his operations and founded the city of Québec: Le Chateau Frontenac. A real dinner in house with a bottle of local, i.e. Chambly/ Richelieu beer with the apropo name “La Fin du Monde” (“The End of the World” or Gespeg > Gachepe >Gaspé in Micmac) was a fitting end to a great and successful trip.

Now back to reality, the University of Maine in Orono, to teach summer school, to help out with the tuition of two of my kids who are still in college.

Across from the Chateau Frontenac, Québec

Rounding the Gaspé

1000 miles solo by sea-canoe

Part II: Québec - Gaspé - Chaleur Bay - Campbellton - Matapédia

(650 mi -1000 km)

By Reinhard Zollitsch

Back in the saddle again

Finals were this morning, tests are corrected, grades made out, the gear is all packed, the boat on the car - Nancy and I are off again to Québec/Lévis. Official start of the trip is early tomorrow morning, August 6, 1999.

This time I had all the charts I could get, large scale, but better than a road map. However there are large stretches of the St. Lawrence for which there were no charts other than detailed charts for the major harbors. Again I was chartless for a total of 130 miles. Enlarged road maps would have to do again, and I would navigate by church steeples again, which are well marked and very visible on prominent landmarks.

The boat felt more sluggish this time. I had crammed food and gear for 25 days into two crates and dry bags, all properly tied down in the boat and 6 gals of water. A neat feeling not to have to stop at a supermarket in every port, but be selfcontained, just add water.

With my experience at St. Antoine de Tilly still vividly in mind, I tried harder to find overnight spots where I would not be stranded 1/2 mile off shore at low tide and would have to portage in or out the next morning. The first two overnights happened to be in small ports with marinas where I was quietly and unobtrusively tucked away in a low-visibility corner, while still enjoying the deep water and launching ramp.

Berthier sur Mer was very welcome the first afternoon when the wind increased to 20-25, i.e. whitecaps and streamers. I learned that the islands off Berthier, La Grosse Island specifically, were used as the “Ellis Island of Canada”, the quarantine islands for newly arriving immigrants. A tour boat takes curious visitors over there, or maybe the grandchildren of the immigrants who were processed there and started a new life in Canada.

With a 4:00 am high tide, which by the way did not progress its usual 50 minutes each day but stayed there till I got into the open Gulf of St. Lawrence, I got up with the tide and was in my boat at 5:30, just before sunrise. This way I could get my boat in the water without a major portage, could take advantage of the ebb tide and enjoy the relative calm of the early morning.

I really began to enjoy this routine, even though it meant I had to pack almost all my gear the night before, including making and packing my lunch PB and jelly sandwich, and forego my morning coffee. Cold cereal with powdered milk was quick and easy and sufficient.

Low tide on the St Lawrence

St. Jean de Port Joli, “Pretty Harbor”, was my second stop, but then extended mud or rather “rock flats” had to be negotiated, at times 5 miles out into the ever-widening St. Lawrence. Fortunately the weather was half-way OK, because I felt very forlorn 4-5 mi off-shore with nothing but mud and rock to my right. This is not a place to be stranded.

Anse de Sainte Anne, St. Anne Bay, was a massive expanse of shallows where I almost got stuck right in the middle, when I suddenly noticed that the water to my left was also shoaling and running dry. I sprinted to the last open tidal stream and made it out finding myself almost on the opposite shore, so it seemed, but not quite.

Hot and tired from all the sprinting and paddling in the shallows, I stopped behind the breakwater off Orignaux Point, where a friendly fisherman offered me his fishing shack right on the rocks for the night. I was delighted and felt honored by the confidence of the old man, who seemed to be impressed by the fact that I made it all the way from Québec to here and was thinking of rounding the Gaspé.

I eagerly carried my gear up to his shack to move in, when I noticed it was locked again. I figure the old man had watched me unload, then turned to go home, and as he had done for I don’t know how many years had automatically clicked the padlock shut, without really noticing it. So it was plan B: I pitched my tent right smack in front of his shack and enjoyed a spectacular sunset.

Spectacular sunset at Orignaux Point

The next day was one of my hardest and most difficult days. I made good progress, but then the tide ran out again furiously, leaving the entire area from the town of Kamouraska to the string of long islands totally dry. I had to go outside of everything again. By then the tide had turned and was picking up speed, in some areas where I definitely did not want to be, up to 8 knots.

But I had the wind at my back; that helped, but only to a certain degree. 20-30 feet off the steep shore of the islands, the tide began to develop a rip. So I had to hug the rocky shore as close as possible, just far enough away to avoid the backwash and power my way against the tide along this narrow eddy-like corridor around one island after the other. I was sweating it out and working hard and my adrenalin was running. It was a challenge, a real one at that - - a no-mistake situation.

I finally made it, inching my way around the last long island, La Grande Isl. Kamouraska will be a swearword in my vocab for a long time to come, but I was eventually rewarded with one of my most scenic stopovers on Le Cap, where I found a small grassy area between two small headlands with the Le Gros Pélerin Isl. outlined in my tent doorway. YES!

Riviere du Loup was a good service stop with phone, water and bathroom, but the breakwater at ebb tide was a doozy. The inside sneak worked again. Then past the only commercial harbor I saw along the entire St. Lawrence shore, Cacouna, and into major shallows building from the right. On the left a long thin incredibly green island or spit of land was making out. I was off the chart again so I could not tell whether that island was connected to shore with a bar, or whether I could just make it across.

This was also the place where I first saw those huge arctic gray seals, which one finds either north of the British Isles or at the mouth of the St. Lawrence. Big husky fellows with broad shoulders, distinctly heavier than our Atlantic harbor seal, with a big rounded-off torpedo-like head without the usual dog-like nose ridge.

Well, I made it through with the flood tide running with me most of the way - one big eddy behind Isle Verte, one of the early homesteading islands. The island was gently tipped towards the south, supplying perfect growing conditions for early settlers. A bit further down the river and also a bit further out was Isle Basque where there used to be a Basque fishing station, just across from the rich Sagenay R. and fjord attracting not only fish but beluga and other whales. But I found my absolutely perfect spot for the night on a tiny island between Isle Verte proper and the town of Isle Verte.

Precarious overnight near Isle Verte

It had a small flow-through beach towards its NE point, i.e. water was coming in from two sides with just enough dry ground at high tide in one corner for my 5X7 tent. The 4:00pm high tide was just right with about 12” of rise as a safety margin. However the 4:00am tide, as I found out at Port Joli, is about 1’ higher. It was close, but I tried it. I could always move up the rocks, if it came to that. My boat was already perched, i.e. suspended in air along the rocks.

The tide and seaweed were right up to the little dyke that I had built around my tent. I loved it and pushed on before sunrise, feeling I had finally gotten into the swing of things, had adjusted to the harsh conditions of the St. Lawrence and could handle them with prudence.

Beginning to feel good

A calm morning and a good mood carried me rather swiftly past Basque Isl. and then to a long stretch of nothing, that is the towns, the road, civilization as we know it, just disappeared and instead there were miles and miles of steep shore with jagged points and headlands, and huge glacial boulders extending way out into the river.

The waves and swells were breaking nicely on those rocks giving away their whereabouts. But I was still off the chart and grew a bit apprehensive. I had no idea what was around the next corner. Where could I take out in an emergency? Not on this type of shore for sure.

The high from yesterday quickly vanished and I was all eyes and ears while I hopped from point to point. Suddenly I came to a point with two people on it. I had to verify my position. So I shouted towards them so they could hear me over the breaking waves: “C’est Pointe a Cives, n’est ce pas ?” And I loved their one word answer: ”Oui”. “Bon” was my return as I paddled on knowing I was still on track.

But soon there was another point, much bigger and badder than all the others before, and since I had been in my boat for almost 8 hrs, I decided to leave that problem for tomorrow and think about it for a while and hope it would shrink with time. Fortunately there was a beautiful crescent cove right before Cap a l’Orignal (Moose Point) at the small town of St. Fabien with a small road running down to what looked like a public landing. Perfect, I’ll take it. It turned out to be the launching site of an Avon type tour boat showing passengers this cape and the next one, Cap Corbeaux (Raven Point) and maybe even Bic Island a bit further off shore.

But everything worked out fine, and I had a wonderful early morning start the next day. And what spectacular scenery it was. By far the most impressive so far. I’ve got to show it to Nancy some year, I thought as I paddled into the sunrise rounding the sheer jagged cliffs on my right. The mountain range and headlands appeared like a black silhouette against the blinding early rays of the rising sun.

The tide was running out, the wind was calm for a change and I was enjoying myself immensely till I ran out of water just before Rimouski and had to stay outside of Barnabé Island. I stopped at the NE tip for an early lunch, admiring the speed of the catamaran ferry boat coming out of the harbor, when suddenly out of nowhere my boat was sucked off the ledge, then flushed back onto the flat ledge, where it was sitting high and dry for a moment.

I had my hands full saving my lunch, field glasses and boat from the horrendous wake of the ferry. I tossed my lunch higher on the rocks, slung my field glasses around me and put the boat on the next big wave to float it back into its element. Now I understand why small boaters are complaining so much about the Bar Harbor, Maine to Yarmouth, Nova Scotia cat-ferry, which tears across the Bay of Fundy at a speed of 40+ knots. Small boaters beware!

After a brief stop at the ferry dock for a phone call and to replenish my water, I was on my way again, till after 9 hrs in the boat I had had it for the day. Then suddenly I saw a huge banner gate in the water in the bight of Sainte Luce, the finish line for this year’s world sea kayaking championship. What a great finish for my day I thought as I went through it and headed for the beach near the breakwater beside the church.

Rain, wind and Gore-Tex

Sipping my coffee that afternoon I was thinking about the race from across the river in Forestville to here, 28 miles of open water - I am impressed. Then more reading, mostly Farley Mowat’s new book The Farfarers, to stay in tune with the surroundings, and more writing in my trip log.

After a beautiful day yesterday, I knew I was going to pay for it somehow. Towards evening the wind picked up, then it tried to force my tent to its knees, but it stayed up. Then came the wind shift, and the waves were suddenly crashing on my beach, and the tide was rising, and I noticed about 4:00 in the morning, that I was distinctly too close to the water.

The waves were running up the beach stretching their fingers towards my tent and depositing seaweed right at my door as a warning. It was close to high tide, but I could not take chances. One wave in my tent and everything is wet for the rest of the trip, especially my sleeping bag. So I hastily packed up my gear and tossed the dry bags into my boat. It was raining to boot by now, and I had to don my Gore-Tex suit to take down the tent. What next I thought. I opted for two granola bars and face the elements before it got much worse.

I was barely settled in my boat with spray-skirt tightly cinched around my waist, when the floodgates of heaven opened. I steered a compass course real close to shore, because I could not see a thing. It was so bad it was funny. I got wet to the skin despite my rain suit and had to push on to stay warm. After rounding rather intimidating looking Pointe Mitis, dancing around the lighthouse and through the ledges and ledge islands, I finally ran out of steam and had to stop for lunch. By then the rain had stopped, but I was still shivering. Only 5 more miles to Sable Bay, and I had covered another 25 miles.

Then the sun came out blazing hot and I got everything dry, including my sleeping bag, which had gotten wet after all. The next day was uneventful and I could cover the 28 miles to St. Félicité in 8:25 hrs total time. The shoreline had flattened out, and the road and houses came right down to the big river. But Québécois rural architecture is nothing to write home about. It is very plain and utilitarian, only the churches stand out, often as miniature copies of a European cathedral, but with a shiny aluminum roof.

Just before St. Félicité I saw my first pod of whales, about 5, surfacing a couple of times on their way out into the open bay. My whale watch that afternoon from my high perch near the town ramp was unsuccessful.

Cap Chat, Cap Reynard and a few more points

The next day the scenery changed abruptly - steep shores and one headland after the other. When I finally saw the 100 or so huge wind generators on the hill, with a lighthouse at the point, I knew I had reached Cap Chat. The giant three-bladed propellers were all turning swiftly in the strong westerly wind, and I could clearly hear the whirring noise over the noise of the breaking waves.

What a visual intrusion on the landscape, as well as a noisy disturbance of the peace and quiet. I made it around the point holding my breath, then beached my boat about 1/2 mile down on a beautiful warm sandy stretch. Just what the doctor ordered, after 30 long miles. Life was great that afternoon.

But then I paddled off the chart again, for 60 miles to be exact. It was more of what I had encountered yesterday: steep mountains and one point after the other. After a while they all looked the same and were difficult to identify. To Cap Reynard was 25 miles, or three churches and a light-house on the right. It was beautiful, but eerie and lonely.

In Sainte-Anne-des-Monts, or “Mountain Annie” in my lingo, I met three sailboats from Connecticut, the Yankee Lady, Misty and Second Wind, who were on an even bigger adventure than I. They had started in Connecticut, went up the Hudson River into Lake Champlain, and on like me to here and planned to round the Gaspé and eventually, next year that is, Nova Scotia and back to Connecticut. Which should prove that New England, including parts of Canada, is an island. After my brief service stop at the marina, we left about the same time, and I did not think I would ever meet up with them again, but I did, three more times, before I left them behind in the fog around Gaspé.

Cap Reynard loomed tall above me with a darkening sky behind it. But I was happy to have covered 300 miles since Québec. This was the halfway-point around the Gaspé, well almost - and people had already named a Cape after me. (Just kidding.)

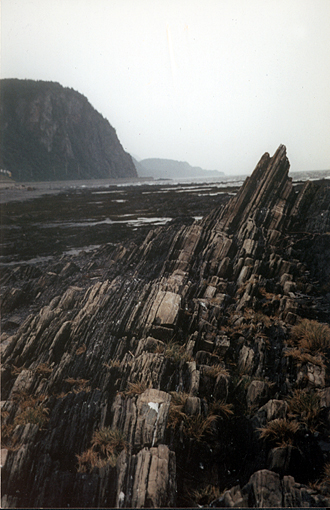

Toothy shore at Cape Reynard

It rained all night, the morning was dark and gloomy, and the tops of the mountains and headlands were enveloped in a shroud of thick fog. But by 8:00 I thought I could do it. I set up the boat near the water on rollers, secured everything well, waited for a big wave, pushed the boat with the returning water into the river, jumped in, at least with one foot and butt, paddled like hell through the next couple of breaking waves. Then I could relax, get the other leg in, zip up the spray skirt, check that I did not leave anything behind (would that ever be a bummer!) and get out of there and into deeper water. My boat with all the gear for 25 days is simply too heavy to hitch myself into the water like a seal, sitting prim and proper in my cockpit.

It was an exciting day, but I was glad to see the imposing face of Mont St. Pierre and find the little harbor of Mont Louis 25 miles down the coast. It is very reassuring to find the name of the harbor on a sign on the boat ramp, where I parked my boat amongst the handful of fishermen’s boats. As you most likely know, fishing for ground fish is practically over in these waters. It is quiet out there, except for a few hand-liners in small clinker-built open outboards. No lobster boats and lobster buoys either in August. Just empty ocean, beautiful in its starkness.

I had caught up to the Connecticut sailors, and I was to share the next harbor, Grande Valley, with them also. By then I was finally back on my chart, and my confidence grew somewhat. What was unnerving for me though, were those 5 to 10 mile long stretches where the road went right along the St. Lawrence with a 30’ concrete retainer wall straight down to the water. That made it impossible for me to take out in an emergency.

But I made it fine to the Grande Vallée breakwater, having chalked up another 27-mile day, even ahead of the three sailboats.

Later that afternoon, the entire town in cars, motor- and mountain bikes would drive onto the breakwater and gawk at the 3 sailboats from the States, a major attraction for this little out-of-the-way town. My boat was as usual camouflaged on the beach as white driftwood, and my tent was a little green speck on a small spot of grass tucked away in some corner. Nobody stopped to chat, nobody knew I was there. I liked that.

I was past the most northerly point of my trip by now. I noticed each morning that the sunrise had moved from the right of my bow to the left. Geographically, I was going down to the Gaspé now. One more overnight in Anse-a-Valleau, where I was invited to a scrumptious chicken dinner by Jean-Yves and Rachel. I was getting apprehensive about rounding the Cape.

The weather reports were only in French, and not having accurate weather and tide information made me very nervous. I had asked Jean-Yves whether he could get them for me, and he did, plus giving me lots of other information about the Forillon National Park at its tip. Thanks, Jean-Yves.

Cap Gaspé – “the end of the world”

With more confidence, I was headed for Cap de Rosier the next morning, where I wanted to hole up before rounding the “baddest point of them all”. But since I did not find a harbor, ramp or even beach where I could take out, I was drawn by the lure of the lighthouse on its point—and there it was: Cap Gaspé, in the distance, a sheer rock face, a formidable looking, long black silhouette with the sun behind it. Awesome. I poked my boat around the lighthouse point, because sometimes it is easier to go ahead in the waves than turn and head back. I looked around the corner and saw what looked like a breakwater with some buildings, maybe even a small harbor, about 3 miles down the coast, and I was going for it.

I was real excited to have made it that far having the Cape within sight. I made it fine to the harbor, found a small tidal arm to the right with a dock and some level grass beside it. How perfect can it get? Just to make sure, I went to the park check-in station to tell them what I was doing. I soon regretted my honesty because I was met with almost hostile inflexibility. “No camping except on assigned sites.” OK, I thought, gimme your closest site, but remember, I come by boat and not by car. It was absurd, and even the supervisor was not willing to make an exception for a boater who had come 750 miles to round the Cape.

I was not willing to take out about a mile and a half down the way on a rocky beach with waves breaking on it, then find a small footpath and portage my gear a good 1/4 of a mile to site #87 on B loop (or was it #285 on C?). Frankly, my dear... I filled out a “comment sheet”, using the word discrimination, which always gets everybody’s attention, but also made a positive suggestion to address the new problem of sea-kayakers and canoeists and establish a specific area for them to put up their minimal tents since the park was blocking out about 20 miles of coast line. Assigning them a place to camp near the water makes more sense than chasing them off the rocky beaches around the points, which small boaters are forced to do with the present policy in place. All to no avail.

I got back in the boat, not knowing what I was going to do. Backtracking 5 or more miles did not appeal to me. So I talked to the skipper and 2 crew of the tour boat which was to leave soon. No problem, they assured me. There is no wind out there, promise. And I fell for it, because I wanted to believe it. I had paddled only 61/2 hours today. I could do it, I thought hopefully and still somewhat upset.

It went beautifully all the way to the point.

The mountains, the end of the newly established International Appalachian Trail, were dropping straight down to the water, I guess ~500 feet. Gray seals were everywhere. The tide was still going out till 4:00. I took pictures, I felt great - till I got to the point. Then suddenly all hell broke loose. Suddenly there was wind being funneled around the point, first right on my nose, then more and more on my left beam as I turned the corner, and then more aft. A tidal rip not more than 100 feet offshore forced me to claw my way real close around one point after the other, one ledge after the next.

I was working hard, making minimal progress and was seriously doubting my decision to round the cape at this point. Waves were breaking, and I was dancing, bracing, sprinting and bracing again, but I hung in there and made it. The tour boat had also rounded the point and was putting its bow under, making it a very wet ride for those on the open deck. It was also ebbing out of the 20- mile long Bay of Gaspé and the wind was building out of the south. I had no rest till I got to the tiny harbor of Grande Grave, where I simply gave up. I was spent after 9:45 hrs in the boat. It had taken me 3 extra hours to cover the 11 miles around the point.

Cape Gaspé - the end of the world

But then standing on terra firma again, everything was suddenly calm and surreal. It was Saturday, and lots of people had gathered in the harbor, to picnic, fish, look, hike, go sea-kayaking or whale-watching. I had decided to stay here, Park-ranger or not. They would not find me - and they didn’t. Instead I met a lot of friendly people wanting to hear about my venture, kids who had never seen a boat like mine, a bent-shaft carbon fiber paddle, tent, self-inflatable sleeping pad or chair like my Crazy-Creek chair.

Kids and parents tried out everything of mine, including my sleeping bag. It was fun. In return they came by later offering me food and drink and assured me they would not tell the Ranger but rather approved of my illegal action. It was heart-warming. A wonderful sunset out my tent door crowned an otherwise very taxing day.

Gaspé – Cartier’s 1534 landfall

From here up the bay into the harbor of Gaspé the next morning was a trip full of history for me. In 1534 Jacques Cartier sailed up this bay, and made Gaspé harbor one of the first landfalls in the New World. From the Straits of Belle Isle between Newfoundland and Labrador he circled around the Gulf of St. Lawrence, going down the west coast of NFL, touching on the Madeleine Isls., Prince Edward Isl., Miscou Isl. in New Brunswick, into the Chaleur Bay, where he briefly stopped in Port Daniel and then in Gaspé, always looking for a sea-way to China. After rounding the Gaspé he went across to Anticosti Isl, missing the St. Lawrence completely, thinking it was just another big bay, and eventually drifted back to Belle Isle.

It was a long quiet hitch up the bay to the long low sand spit arcing out from the left shore making Gaspé a perfect natural harbor. I imagined Cartier rounding the point, dropping anchor off the sandy beach on the inside of this crescent peninsula, and checking things out. Maybe going ashore for some birds’ eggs, doing some fishing, repairing or cleaning the boats and most importantly, finding out who lives along its shores.

It was Sunday; the church bells rang as I stepped ashore - it was an awesome moment in time.

After lunch I headed down the bay again on the western shore where I wanted to stop just before the next big point, St. Pierre Pt. I was back to my old plan: exposed points are best rounded in the relatively calm early hours. I learned my lesson the day before, rounding the Gaspé. Impatience does not pay.

And I found the perfect little hide-away, a tiny harbor near Cap-du Bois Brulé, where I nestled my tent and boat between old hauled-out fishing boats. I felt very alone there, till who should appear, but my three Connecticut sailor friends who had spent the previous night in Gaspé. But that was the last time I saw them, even though we were both headed towards Campbellton. Fog and headwinds must have slowed them more than me.

Percé Rock

The next day was spectacular. St. Pierre point was impressive, but even more impressive was the view from there across Malbaie Bay towards Percé Rock and Bonaventure Island with the spectacular mountain range to the right of “The Rock”. The sea was calm, but fog was drifting in from the ocean, slowly but surely enveloping Bonaventure, then creeping up on Percé Rock. Crossing over to the Rock took a good 1 1/2 hrs, which gave me ample time to admire this gigantic boulder. It looks like the “Prudential Rock”.

Percé Rock from St. Pierre Pt.

It has sheer sides and a most enticing arch at the eastern end of it. Since the tide was low, I had to go around it, which I had wanted to do anyway. And when I came to the arch, I felt very tempted to thread the eye of the needle. It was shallow under the arch with lots of chunky rocks, loose ones that did not grow there, but must have fallen from above. I sized up the situation, then kicked up my rudder, and paddled hard and went for it. The wind had freshened and was pressing hard through the arch. I scraped a bit here and there, but it was worth it. I had always wanted to do it, even back in 1963. So now I did it, and the rocks decided to stay up where they belong.

Percé Rock

While “The Rock” looked just the same as it did 36 years ago, the surroundings had changed drastically: there now was a dock with boat tours, rock- and whale-watching, a tourist information pavilion with stores etc. etc., the works. A quick phone call home, some unbelieving tourists from all over the world, even China, staring at my little boat and asking sweet, naive questions. A smile on my part and I was gone across the next big bay to Cap d’Espoir, Cape Hope.

I liked that name (better than the English corruption of “Cape Despair”). I had paddled 28 miles today and had been in the boat for a total of 8 1/2 hrs. It was time to quit. I had earned my afternoon coffee, swim and reading. I also had read about Cartier having had trouble rounding this point, since it has a very long shallow bar extending far out into the bay. So I decided to tackle it in the morning.

The worst day of the trip

The calm protected cove just before the point was quite different in the morning. The wind had shifted to the NE and the waves were breaking on my rocky beach. So it was one of those plan B launches again. Put the boat on rollers, pack it, then push it in the water on a big breaking wave, jump in and paddle like mad before you get smacked by the next breaking waves, which would not be too cool, because the spray skirt is not zipped shut.

So this is how this day, which turned out to be my worst day, began. When I tried to jump into the boat my sandal got stuck in the thick seaweed and almost tipped me and boat into the water when I tried to pull my leg in. But one big jerk freed it, but “sans sandale”. I can’t go on without sandals, I thought. So I beached my boat again. With one hand I tried to hold the boat into the waves and seaweed slop, while looking for my sandal in the goop. I found it, threw it in the boat, pushed, jumped, paddled all at the same time and threw my back out. The boat looked like a mess, I was wet, on half power and upset with myself that I let it happen with almost 200 miles still to go.

The point looked hopeful, some old swells coming in and breaking here and there, but nothing that I cannot handle, I thought. I kept a keen look-out for the big breaking waves - all is fine, till I suddenly see a humungous wave rolling very threateningly towards me, it builds from over my left shoulder - OH NO, I yell, and steer and paddle as fast as I can right into it - - and then it hits, hits me right in the chest and my face, but the boat punches through the white water. I reach over the break with my paddle and dig in deep on the other side of the wave. Phew, that was close, and I am wet again, wet down to my underwear which I had just changed this morning.

Later that morning with the waves still trying to pass me from behind, I suddenly notice a big black round torpedo-like thing with its own bow wave like a submarine or TORPEDO aiming right for me. Had I drifted into another target practice range like on Lac St. Pierre? I sprint, the “thing” is still aiming right for me. My heart beat races. What now? Brace for impact! - which I did, slapping my paddle on the water like an outrigger, waiting for the inevitable to happen. But nothing happened.

I look all around, nothing.

Then I see a huge seal behind me looking at me dumbfoundedly with its big eyes. He must have been surfing this wave for quite some time, just for fun, and suddenly saw or heard me slap down my paddle. I was so glad he could stop on a dime, because I could clearly see him just feet from my boat. Reading up on those seals in the Gulf of St. Lawrence, I learned they are gray seals, growing up to 9’ long and weighing as much as 650 lbs. Colliding with one of them would have most likely flipped me. Not a pretty picture.

Then the wind picked up coming at me over my left bow and I was dancing again, barely making it around the breakwater into Chandler harbor where I suddenly saw a shipwreck, a big Panamanian freighter high and dry on a ledge. Not a friendly sight. I had planned to round two more points and make it to Newport, but I simply did not have the heart and stamina today to go on, so I didn’t, and pulled out on a long sand beach in the inner harbor. I even indulged myself and ate out at the Chandler Marina just up the beach, the first and only meal out on this trip.

Cartier’s Port-Daniel

For the rest of the trip the wind stayed in the S and SW, which made the going quite rough. Pte. Noire and Pte. au Maquereau were beautiful, lonely and rough, and I welcomed the little well-protected harbor at Anse au Gascons for a lunch break. I was sorely tempted to stay, but mustered enough energy to poke my bow out between the narrow harbor breakwaters just to see how things were. They had not gotten much worse, so I went on, point to point to point till I was suddenly headed up into Port-Daniel, where Cartier had landed in 1534. I dipped my hat at the cross at the harbor entrance to commemorate the event, then rounded the entire bay, to end up just before Pte. de l’Ouest, West Point, which I would tackle the next morning.

After 8 hrs in the boat, I found a perfect level area high on the seawall, with a steep shore and trees behind it to give me some shade. A perfect spot to “celebrate” my 500-mile marker since Québec or 850 miles since Whitehall. I felt very accomplished, and my back was beginning to cooperate again.

The next morning was one long hitch to the SW, 16 mi, right into the wind, which was increasing to 20mph, gusting to 25. Paspébiac harbor was a welcome stop for lunch. It was a large fishing harbor, which had seen better days. Most of the buildings on shore had been turned into an open-air museum commemorating former fishing greatness. I walked through the exhibits, stopped in the restaurant and was served coffee and raisin pie by waitresses in historic costumes. What a nice touch. Then I was back in the saddle again, riding my bucking bronco due W towards Bonaventure point, but pulled out just short of it behind a breakwater at Sawyer point where I found a nice spot on the beach for the night.

Looking towards the finish

I loved rounding Bonaventure Point early the next morning, because I felt I was on the home stretch. I was going NW now, all day, and getting into the last funnel of Chaleur Bay. At New Richmond on the Cascapédia river I had paddled another 25 miles and it was time to look for an appropriate place for the night. Point Duthie looked good on the map and had the only deep water near shore in the entire terribly shallow Cascapédia Bay. A tiny beach with some level ground behind it, even grass, seemed the perfect jump-off point for tomorrow’s early hitch across the bay.

Later that afternoon some people came down to my campsite. We were both surprised to see each other. It turned out I had pulled out on the shore belonging to the Stanley House, the house former Governor Lord Stanley had built, much of it with his own hands. Which Stanley you might ask? THE STANLEY who donated the coveted Stanley Cup in hockey. I had to see that house, even if that meant jeopardizing my overnight camping spot.

The Stanley House

So I followed the thin trail through the woods up to the guest house and introduced my shabby, bearded self to the owners who, instead of chasing me off their property, gave me the grand tour of the entire house including the beautiful antique kitchen with all its original pots and pans, dishes, chinaware and wood stove. And then they wanted to see my set-up and boat.

What genuine warm people the Le Blancs are. The three guests from NY seemed to enjoy themselves on the spacious veranda framed by gorgeous rose bushes. I felt transformed to an old British country estate for a moment before I returned to my humble abode and Hormel Chili with beans.

With a spectacular sunrise at my back, I crossed the bay early the next morning, hoping to get to the end of Chaleur Bay and the mouth of the Restigouche River at Dalhousie for the night, and I did. I did not quite have the guts, though, to cross the 5 mi Tracadigache Bay to Pte. aux Corbeaux (Raven Point), but I crossed it in two hitches, one from Pte. Tracadigache to Saint Omar, and then from there to Raven Point with the Dalhousie paper mill behind it belching white smoke into the sky. I am getting back to civilization, I thought.

Every Raven Point I rounded on this trip had ravens when I passed, and this point was no exception. Three ravens were giving an aerial ballet performance overhead, diving and rolling with the utmost of grace. I enjoyed watching them while the tide was slowly pushing me up the Restigouche River. But I could see that the stretch between this point and the next, Miguasha, looked as if it could get real rough, especially in an ebb tide with any easterly wind blowing against it.

The shore looked gouged and scoured by ice and waves, several big eddies could form, and the river was awfully restricted here with big, often deep, bays holding lots of water above this bottleneck. I pulled out on a beach near the ferry dock to Dalhousie on the Miguasha side. Two more river days to Matapédia, unfortunately using a road map for navigation.

The fjord-like arm from here to Campbellton was a wonderful surprise, but was everything but a river in the New England sense. It was more of a string of large interconnected bays with a strong tidal flow. I followed the N shore hopping from point to point, but one of the hops took me 2 1/4 hrs to do. That is one big hop for a tiny boat like mine, and of course the wind was picking up at that point, NW 20, right on the nose all the way to Campbellton.

I saw the lighthouse and the long, tall retainer wall on the left shore before it. There must be a nicely sheltered harbor with marina, phone and bathroom right around the corner, I thought. None of the above. By now the tide was ebbing, and the wind was blowing so hard that I could barely make it up the river to the town. The current along the retainer wall was so strong (a good 5 knots) that I could not make any headway, but had to try my luck farther out in the river.

I finally made it to the huge bridge spanning the entire bay, still looking for the perfect take-out, because I had to get to a phone to arrange tomorrow’s take-out in Matapédia. Then I saw what looked like an abandoned boat ramp, all broken up, totally unprotected from wind and current, ending up in a field of deep, black, oozing, sandal-eating mud. And more mud upriver as far as the eye could see.

Like it or not, this was it. I took a mighty run and stopped close to the old ramp pavement. I jerked the boat out, unloaded and set up camp at the edge of the ramp above the high tide mark, but left the boat at the water’s edge to be washed at a later stage of the tide, before I would portage it up to my tent.

Up the Restigouche to Matapédia

All’s well that ends well. I found a phone, set up a pick-up for tomorrow, had one last Dinty Moore beef stew with canned fruit for dessert, coffee with creamer, leaving just enough of everything for one more day. Even my two loaves of bread lasted 24 days without turning into fuzzy bunnies that need to be stroked every morning, i.e. have the mold scraped off, which I remember quite vividly from my early sailing trips on the Baltic, North Sea and North Atlantic. (Two loaves of bread for 24 days?! No wonder I lost 10 lbs. that I didn’t need to lose...got to eat more next time.)

Another gorgeous sunrise sent me on my way up the river past Tide Head to Matapédia. It had never occurred to me that I might run out of water here, since the entire stretch to Matapédia looked more like an extension of Chaleur Bay than a shallow salmon stream—which it turned out to be.

Up the Restigouche River

It took me 5 hours to cover the 15 miles up-river. I had to get out and pull my boat about 20 times, slip-sliding and tripping on those slimy round river rocks which the salmon like so much. I was ready to pull out many times, but found no way to the road. Then I saw a fishing camp with a good 50 salmon boats, long wood-and-canvas canoes with outboards. It must be getting better I thought. If they can do it, I can, and I did, but barely.

I dragged my boat up the rapids to the tall route #134 bridge just before Matapédia, our rendez-vous place, but could not possibly take out there because of the steep banks. So I paddled, poled, waded and dragged on till I could see a motel sign. That must be the Restigouche Inn in Matapédia where Nancy had reserved a room for the night, before we would head home for Maine. It was.

End of trip

THIS WAS IT, it dawned on me, 1000 miles since Whitehall on Lake Champlain, 650 miles or 1000 kilometers since Québec; 37 days total, or 24 days since Québec. My longest trip ever and keeping up a 27 mile per day average for a 60 year old geezer - not bad I thought to myself. What a boat, what paddles and gear.

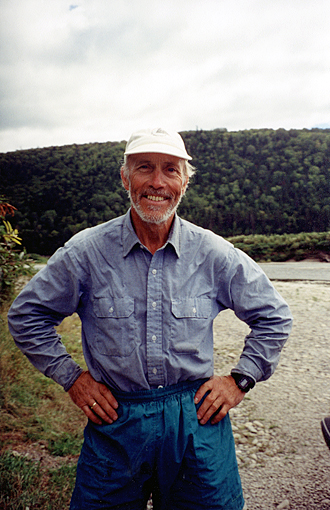

"Old Teach" with the 1,000 mile smile

Thank you Verlen Kruger, Eugene Jensen, Barton, Eureka, Thermarest, Goretex, Crazy Creek and many more for all the wonderful high-tech and affordable equipment. No, I have no sponsors; this is my heart-felt, sincere personal “thank-you” for your dedication and effort to make equipment better, lighter, stronger and user-friendlier.

While I was still unpacking my boat and washing it off, a reporter from the “Voice of the Restigouche”, the Campbellton paper “The Tribune”, stopped by for a brief interview.

I was stunned, but I learned the motel owners had phoned the paper.

Minutes later Nancy showed up in our familiar looking VW Golf, right at the edge of the river where I had pulled out. Even the pick-up worked out perfectly. I was very glad to see her and very thankful for her strong support for my canoe ventures.

Life was lovely at the Inn: a shower, dinner in the fancy restaurant (Restigouche salmon and fiddleheads), and a comfortable, soft and level bed. And while I was trying to unwind and fall asleep, my mind was already planning next year’s trip: Maybe I’ll go on along the New Brunswick shore to the Prince Edward Island bridge and finish my trip around the island.

And then on towards Canso Strait between Cape Breton and Nova Scotia, and yes, I could even get back to Maine that way without a car shuttle... but at that time I was already in dreamland and don’t know anymore where the trip was taking me.

© Reinhard Zollitsch

BACK TO TOP OF PAGE