LEWIS AND CLARK PLUS 200

By Reinhard Zollitsch

June 2003

THE BICENTENNIAL YEARS

One day in the depth of winter “Old Teach” here was looking ahead towards the end of the school year (just like his students) and wondered what exciting and challenging escape from society he could plan for himself. Lying on the beach in Aruba sipping cold drinks or hanging out in some hotel or amusement park in Las Vegas or Florida, wasn’t really my type of R&R. I’d rather be doing something, preferably in a small boat, on the ocean or big river, all alone if possible.

But June in Maine is cold and foggy, and venturing out onto the Atlantic in those conditions would be wasting a perfectly good coastline. Then I came across a small note in the paper reminding me that the years 2003-2006 mark the bicentennial of the Lewis and Clark Expedition and had been declared Lewis and Clark years.

I had always admired those two explorers and their intrepid “Corps of Discovery” (42 in all) who accepted Thomas Jefferson’s mandate to find a water route to the Pacific. It was in 1803, the same year the Louisiana Purchase treaty was signed (which almost doubled the then United States to the West of the Mississippi), that Meriwether Lewis and William Clark started planning their journey, being allowed $2500 from Congress to accomplish that feat (whoopee!). (“Lewis and Clark” from now on in this article referred to only as “L&C”.)

L&C and RZ

What always truly impressed me about this group was that they never lost sight of their goal, the successful completion of the trip to the Pacific and back again with all men. (Only one person was lost, most likely due to a medical emergency, acute appendicitis.) What fascinated me further was the character of the trip: It was not a swashbuckling, sword or gun toting crusade or conquest for a distant cause, but a quest, a journey of discovery with detailed trip logs describing and depicting the landscape they traversed, mapping everything as well as they could, plus recording new flora and fauna in every last detail - new trees and plants, animals and fish - as well as the native population in these areas.

They did all this with minimal equipment, complementing their needs as they went along; no high-tech boats (they only used one 55 foot long wooden keelboat and two canoes, and horses of course for the monumental portages), no polypropylene, nylon, polar fleece or Gore-Tex to wear, but rather clammy cotton and wool and soft leather. They of course did not have NOAA charts or geodetic survey maps, definitely no GPS, just a simple compass, a telescope and a basic idea as to where they were going. Those guys were confident, tough and had perseverance, I thought. The more I read about them, the more I had to find out how tough they really were.

WHEN AND WHERE?

But which stretch of their expedition would I check out and when? Being a person from east of the Rockies, I am more interested in that part of their journey, and I am also more interested in starts than finishes. (Their return trip alone is still a great feat but it pales in comparison to their trip out west and their first glimpse of the Rockies and the Pacific.)

Their first major goal as they saw it, was getting to the Rockies and the Continental Divide. They had to follow the Missouri River from St. Louis to the legendary “Great Falls”, the 10 miles or so of waterfalls and cascades, which no white man had ever seen.

That was it - that was where I would start my trip, right below the falls, “the grandest sight I ever beheld” (Lewis, June 13, 1805) and I would paddle on the river on the same days that the “Corps of Discovery” was on this stretch of the river, early June, only I would be going downriver, not upriver.

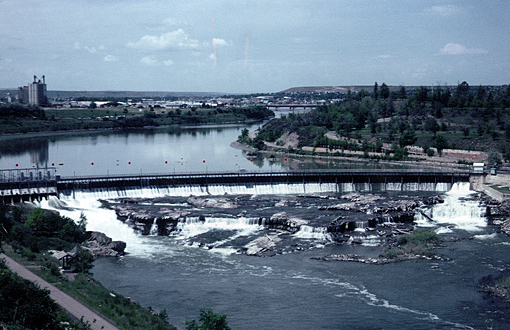

Eagle Dam, Great Falls, MT

While most modern paddlers start at Fort Benton, the beginning of the “National Wild and Scenic River”, I, however, wanted to put in where L&C took out below the Falls and started their month long portage, to make my trip more authentic, and get in about one mile for every year that had passed.

Via the Internet I had ordered river maps and info books (see appendix) and located an outfitter who was willing to rent me a bare boat (an OLD TOWN Penobscot 16 like the boat I used last year on the Baltic Sea in Germany), pick me up at the airport and drive me to the put-in below the last of the five dams, Morony Dam, so that I could get on the river that same afternoon.

Everything worked like clockwork. I had no delays, my two Army duffels arrived with me, and Jim was there with my canoe and a small propane gas tank for my cook stove, as well as my carbon fiber paddles, which I had mailed ahead of time. We drove to Morony Dam, and at 2:30 p.m. (local time) that same day (June 2, 2003) I was off. He mumbled that nobody had put in here for a long time, especially so early in the season with such a vigorous flow... “Just stay left” was his advice.

This was the place all right: Morony Dam sits on the last of the five big waterfalls, even above L&C’s take-out at Belt Creek. I saw the dam release; it was flowing hard and I was in a gorge and it was quite windy. I had to take a deep breath, but I was confident I could do it. All gear was in waterproof bags and tied in, and I used my 7.5 gallons of drinking water (which we had picked up on the way to the river) as stabilizing ballast. I was off, and I knew that this first stretch was going to be the hardest part of the entire trip. I only wished I had brought a bailer or at least a sponge, but I ran out of space in my duffels.

![]()

Click chart to enlarge

in a new window

THE TRIP BEGINS

I soon noticed that river waves are much wetter than ocean waves - they jump on board and won’t let you dance them. After less than one mile I had to empty the boat, but I had to cross the river to do so. When I crossed back to the left for the next set of rapids, I realized how fast the current really was. I switched into racing mode, but still could not make it.

So I got ready to face the waves head on but could not turn the boat, no matter what I tried. A fierce upstream gust kept me in irons and I went over the first drop sideways, then bounded through the haystacks below. I do not know exactly how I managed to stay upright or kept from swamping, but luck was definitely on my side. I accepted it humbly, because I normally do not rely on Lady Luck.

After two hours on the river I figured I had paddled my planned eleven miles for the first half day, and I took out on a level spot on the left bank. It seemed like an awfully long day, with two-hour time change and all, and supper tasted great that night just as the rains began.

I had read about the rains this time of year, but I figured they would nicely swell the river and make everything look green - I’ve got Gore-Tex. I also knew how cold the nights could get, but I was ready for below 40 degree Fahrenheit nights in my warm sleeping bag. The winds, I learned quickly, are calmest in the morning and follow the river downstream, then often reverse their direction in the afternoon and double in strength on their upstream leg.

Again, this was no problem for me, I thought, since I am used to ocean paddling where the same happens. But I have to admit it almost bit me that first afternoon. Even next day I turned a couple of 360s in a gorge and had to use the shore as a pry to turn my boat around. I could not do it with my paddle alone, even hitching all the way to the middle of the boat. But after that I watched my bow like a hawk and would not let it get away from me, and it didn’t.

Early the first morning I came up to Carter Ferry, a motorless ferry angling its way across the river and hanging by two strong cables, one higher and one a bit lower, I had read. This first ferry only seemed to have one higher cable. Great, I thought, while I was approaching at about 7 miles per hour, still on the left side, near the ferry itself, to be safe, when I suddenly noticed the second cable only inches above the surface of the river.

FULL ASTERN! ferrying towards the ferry - and I just made it with a last minute duck of the head. Two close calls in twenty-four hours, a terrible record for me. Self-flagellation and strong reprimands were in order, and the rest of the trip went fine.

FORT BENTON

After 20 miles I arrived at the small town of Fort Benton, the former hub of this world. Paddle wheelers made it up to this place in Spring and early Summer, carrying supplies and settlers till the railroads took over in 1887, which in turn got replaced by our present interstate system of roads and trucking. I tied up at a newish looking town dock with boat launching ramp, just below the old Fort and Bob Sciver’s famous statue of Lewis (the leader of the expedition with spy glass), Clark (the navigator and mapmaker with compass in hand) and Sacagawea (the invaluable Shoshone guide).

L&C's boat, the Mandan

And right beside the impressive large statue was their totally flat-bottomed 55 foot keelboat, the Mandan, a dog of a boat to pull, pole, or row upriver. It had a mast with a square sail, which could not have been too useful on a winding river and ever shifting winds. It looked as if it only carried their supplies without offering any shelter for the relatively large crew of 42 people plus large Newfoundland dog. Each night I picture them therefore camped ashore under tarps and flimsy tents. The boat had no portholes or windows to let in light. A very spartan affair, but what do you expect for $2500 for the entire three-year expedition?

Fort Benton is a great place to start your float trip down the river. It is here that the official National Wild and Scenic River starts, which was designated as such in 1976. In 2001 President Bill Clinton signed a bill to create the Upper Missouri River Breaks National Monument which added thousands of acres of land bordering the river, guaranteeing this river to remain as untouched as it ever was, basically keeping modern development out.

Except for some old farms and small homesteads on the flat pockets of the so-called bottom land along the river, there is not a single modern house, hotel, motel or summer home anywhere along the entire 149 mile stretch. And there are only two access points between Fort Benton and James Kipp State Park at the #191 bridge: Coal Banks at mile 41.5 and Judith Landing at mile 88.5. So it is still a surprisingly out-of-the-way place, devoid of human habitation, well almost. It is a place of history as well as of solitude and timelessness.

On my entire trip I only met four small groups at the Eagle Creek camp site, (one of which I had met before at the mouth of the Marias River), and from there to the end of the trip (100 miles) not a single other person or boat, just the river with its spectacular scenery. It was desolate and lonely. I had never seen scenery like that. It was totally new and immensely fascinating for me. (Later in the season, though, the boat traffic increases sharply, I understand.)

THE SCENERY

Hole in the wall

Yes, I pitched my little Eureka tent at several sites where Lewis and Clark had camped, read their entries in their log for that particular day and place and marveled at their astute observations. Some people get goose bumps all up their spine and feel touched by “The Spirit of History” at moments like that - not me. I am not a people worshipper, but I was touched by the river itself and its often canyon-like banks, the same way L&C were.

The cliffs and hills were constantly changing their shape and color, from white through all shades of gray, to black and rusty red and brown in between. Even the layers themselves were arranged in different sequences and took on the most varied shapes, from massive sheer cliffs and walls at the river’s edge to grandiose castle-like white blocks on a grayish brown hill, complete with thin round turrets, and holes in the wall like large rose-windows in a cathedral.

What fascinated me about reading L&C was that they were so immensely fascinated by the landscape they were traveling through and that they could not get enough of it, and were always wondering what was coming next. This curious positive attitude must have been a major driving force for those early explorers.

I felt that same thrill even today. And as I was sitting in my Crazy Creek chair writing my trip log, describing what I saw and felt that particular day, I was comparing my notes with those of L&C, and I wondered how much those men really understood of what they were seeing. Would they have believed what we now know about the geological history of that region? Those thin walls and those castles and turrets were not magic or man-made, but were simply a product of erosion, nothing more or less.

The walls are dikes, liquid igneous rock squeezing into cracks of shrinking layers of sandstone (like my wife’s cheesecake which always cracks, and which then fills with still liquid chocolate sauce). Staying with the cheesecake image: the chocolate will harden more than the cheesecake, which would “erode” faster than the chocolate, leaving thin “walls of chocolate”, get it?

And no human being or druid put those black slabs of rock teetering on top of those slender white columns or needles. There used to be a solid bed of white sedimentary rock covered by a layer of much harder black rock, again, like a frosting. In some places this black layer has protected large areas of white sandstone, which makes it look like a European castle, or the white sandstone eroded, leaving chunks of that black top layer teetering on slender leftover sandstone columns, till those too would collapse.

But what fascinated me most going down the upper Missouri River was realizing that I was traveling on a river that had carved its bed through an old ocean floor, as I had noticed on the Suwannee River in Florida. I read that 70-90 million years ago, during the Cretaceous Period, an arm of the ocean, the Western Interior Seaway, connected the Gulf of Mexico with the Bering Sea, just east of the present day Rockies.

Montana and many other prairie states (the Great Plains) were under water, and this particular area was built up of sediments from rivers running into this sea. When the sea was deep, the sandstone deposits were dark; when it was shallow, the deposits were more like a white sand bank or beach. The different layering thus reflects the depth of the ocean water at the time of deposit. A most interesting thought for the ocean paddler in me, and I very much doubt that L&C knew that. To them and many of the early settlers, this area was simply magical, and it still is, in its awesome raw and romantic beauty.

Another captivating thought for me, which kept my mind occupied for many river hours, was the realization that the river from Coal Bank (#41.5) to about the confluence with the Yellowstone (about 400 miles) is much younger than the river above that point. The old Missouri River is pre-glacial and used to flow north from Coal Bank to Havre and then east past Malta to the Yellowstone. The last ice age forced the river into a wholly new bed, about 60 miles to the south, and it shows its much younger glacial age.

I was as spellbound by this stretch of the Upper Missouri as L&C were, and could empathize with them as I marveled at the uniqueness of this river, at every bend, just as they must have done. But their extra ingredient was the total newness of the river, while mine was the geological and historical knowledge and perspective. And what a relief for modern river users like me to know that this river with its unique history and scenic wonders is protected in its present state as a National Wild and Scenic River for all to see in all eternity.

ARE WE STILL ON THE RIGHT RIVER?

My second overnight stop saw me at Evans Bend. I had planned to paddle 25 miles a day, which I figured should be very doable even with a strong headwind and in the rain. The current of about 3 miles per hour sure helps. Most days I was at my destination for the day at noon, leaving ample time for exploring, reading, writing, picture taking and even swimming in the still rather cold water.

At the confluence with the Marias River, where L&C spent nine days trying to figure out which was the true arm of the Missouri, I met a group of five canoes. It was raining hard, and we barely made headway in that strong easterly. I briefly stopped to look up the Marias and up the Missouri - it was absolutely clear which was the main arm; nine seconds max but not nine days.

According to Lewis’ diary, this was a very trying moment. “...to mistake the stream at this period of the season...would not only lose us the whole of the season but would probably so dishearten the party that it might defeat the expedition altogether.” (Lewis, June 3, 1805). According to him, he was the only corps member thinking the river went left (Missouri), while all others were convinced it went right (Marias River). To make sure, they camped from June 2-10 on an island at the mouth of the Marias and explored both arms extensively.

June 2-10, when their whole trip was hanging in the balance, I thought to myself when I was planning my trip, would be a meaningful date to be in these waters and experience first hand what the river and the weather, two major factors of every trip, were like. Going down the Missouri in August to me was totally meaningless.

The river could be so low that there is barely enough water to float your boat, or it could even be too bony to run at all, as the old paddle-wheel captains found out. I also imagined the heat to be unbearable at that time of year, and the scenery must have lost all shades of green. From reading L&C I knew that cold, rain and wind were major weather ingredients for the Corps of Discovery, and I wanted to do right by them.

Stopping briefly at the mouth of the Marias River, I also have to mention in defense of the intrepid explorers that the flow of the Marias must have changed drastically since June of 1805, mostly due to the construction of the huge upstream Tiber Dam creating large Lake Elwell. It must have been a real problem making the right decision; otherwise the Corps would not have wasted nine valuable days at its confluence, when they could have pushed further upriver at their average speed of 15 miles a day.

SPECTACULAR EAGLE CREEK REGION

It was raining hard when I got to the white cliffs leading up to Eagle Creek. The raindrops were bouncing off the water, and the air was suddenly filled with a very strong, but pleasant herbal smell. I remembered it faintly, but could not quite place it. So I closed my eyes, took a big whiff, and there it was: Nancy’s sage pot roast.

I loved that warm thought, while breathing in that wet sage aroma through my nose - a real olfactory treat. I snapped a few wet pictures, but the rumble of thunder made me hasten to my take-out at Eagle Creek. I found a great place under a huge cottonwood tree, got my tent up and gear in before the real downpour started. What a sight, as the rain came around the bend of the river towards me.

Spectacular Eagle Creek

As I knew from my reading, Eagle Creek was a must-stop. And when the sun came out again, I realized this was the most impressive, spectacular campsite of the trip so far, no, ever. In retrospect, this spot was the essence of my trip - it had everything. It had history, scenery, geological splendor and riddles. No wonder L&C camped here May 31, 1805, as did the German scientist and explorer Alexander Philip Maximilian, Prince of Wied-Neuwied, with his young renowned Swiss painter Karl Bodmer in 1833 on their way to Fort McKenzie as guests of the American Fur Company.

Theirs was the first pure research trip up this fabled river, even before John James Audubon (1842). It was their account and countless sketches and watercolors of the people and the scenery “which gave the outside world its first glance” of this area, the guidebooks point out (Glenn Monahan, p. 55).

I loved looking at Bodmer’s famous picture “White Cliffs” and comparing it with the real picture out my tent door. It had not changed much; only the bighorn sheep were gone, at least in this area. But there were the same steep white cliffs interjected with a black igneous intrusion, LaBarge Rock, and the castle-like white chunks with towers and turrets capped with larger wheel-like darker/harder rock.

GETTING INTO THE PICTURE

Bodmer’s other well-known picture is entitled “Gros Ventre Indian Camp” and depicts 260 leather Atsina Indian tents on the banks near Arrow Creek at about mile 78.6. When I planned the trip I realized that my 25-mile a day pace would put me real close to this spot. So why not camp there also, put myself into the picture, so to speak, and make myself inconspicuous among the large sage brush and imaginary tall wigwams, and enjoy a traditional, historical and picturesque night on a former Indian site, rather than staying at the official, fenced in, very artificial looking designated camp site at Slaughter River. I knew I would also meet most of the four boating groups from Eagle Creek there, and the name Slaughter River did not appeal to me at all.

"In Bodmer's Picture"

A brilliant move, if I dare say so. It turned into my wildest and wooliest, most authentic and lonely campsite ever. My granite gray tent was exactly the color, size and shape of the larger sage bushes; I had visually dissolved myself into the landscape, and my green canoe disappeared in the tall grasses along the river’s edge. I had flowering cactus at my doorstep and the “Divide”, a mountainous range, filling my tent door. I had carefully checked for rattlesnakes - I knew this was rattlesnake country - but this was too early in the season and too cold for them, I figured bravely. But I walked carefully through the sage of this traditional Indian camp and enjoyed myself immensely. That night, squatting in my tent, I loved telling Nancy in Maine of my whereabouts, during our prearranged brief phone call via satellite phone.

The nights were still cold and the days windy and often accented with rain. But the next day I covered the 25 miles in less than four hours; what a change from last year’s eight hours on the Baltic Sea in Germany. I flew down eight named rapids, which even at this strong spring run-off were nothing but riffles. Only Birch Rapids kicked up a few whitecaps, and the legendary boat-eating Dauphin Rapids purred like a pussycat.

But I have to mention that the Corps of Engineers blasted and removed tons of rock and debris from this stretch in 1879, giving the river a minimum depth of 30 inches! When there was enough water, the paddle wheelers often had to kedge or winch their way up this stretch, after picking up some extra wood from the “Wood Hawks” along the banks, homesteaders who went into a seasonal firewood business.

Those boats would burn 30 cords of cottonwood or 20 cords of hardwood a day, stripping the banks of everything that burns. When the water level was low, the boats often had to unload their cargo, drag the empty boats upstream and reload. Often even that was not possible; boats from farther upstream or ox carts would take over and haul the goods to Fort Benton. In the low water year 1868, I read, 2500 men with 3000 teams and 20,000 oxen were hauling freight from just below here (Cow Island) to Fort Benton. - I have a hard time imagining this, in this totally desolate and deserted area.

At mile 88, at the confluence with the Judith River, the riverbanks suddenly flatten out for a moment and look like pretty good homesteading and grazing land, and of course it was used that way and still is. Now there even is a bridge across the Missouri, with campground and boat ramp. But this is only the second access point since Fort Benton, and paddlers are soon back in their usual, now mostly gray Badland-like, hilly surroundings.

McGarry Bar just below big bad Dauphin Rapids sounded like a good camping spot for me, as it was for L&C on May 27, 1805 and many paddle wheelers before me. The cottonwood trees have all recovered from the steamship days and provide good shade, but sound like there is a storm blowing on the river, and they could drop a dead limb on your tent, so beware. But they are homes to many birds, including ravens, magpies and even eagles.

I also saw an amazing number of Canada geese with their gangly, gray goslings in tow and white pelicans, who must have moved up here in recent years, making the grassy islands look very Floridian. Other wildlife included lots of very unperturbed mule deer along the river, and a bit further down the river at Castle Bluff (#109.5) a group of twelve bighorn sheep, which were recently reintroduced into this area. They were doing what they do best, climbing up an impossible slope or grazing and drinking at the river’s edge.

L&C’s FIRST GLIMPSE OF THE ROCKIES

One more stop on the river before my take-out at James Kipp State Park at the #191 bridge. My trip was winding down, and so was the scenery - it turned a uniform gray, even though the banks in places reached 3000 feet above sea level (I guess about 400 feet above river level). But my last overnight stop at Cow Island was a significant one for this river. In low water years, or later each season, all boat traffic would stop here, and freight was hauled overland by “bullwhackers” (ox cart drivers) up Bullwhacker Creek (of course) to Fort Benton, as mentioned before.

But this is also the place where Captain Clark climbed one of the tallest river hills (3100 feet, about 2 miles north of Cow Island proper at # 124.5) and got his first glimpse of the Rockies, so he thought. (He actually only saw the Bear Paws.) I had to check this out. So after six more named rapids, I pulled out at about #126 near Cow Island and got ready for my afternoon hike. I was about to start, with field glasses, water and hiking/snake stick, when suddenly the bright sunshine and the distant horizon disappeared in an ominous haze, looking like a possible thunderstorm. So I decided instead to climb the highest hill behind my tent on the right bank and see what I could see from there.

It was quite a steep hot climb up over soft crumbling rock. The “mountaintop” was everything but hard smooth New England granite. It was nothing but a half inch of hardened mud crust with loose sand and loam beneath it. I left deep footprints on top of the mountain, then slid down its side almost as if it were a sand dune. My view to the Rockies was blocked by another range, as I had expected, and the thunderstorm was materializing. I had to get down fast or I would slide down the hill on the seat of my pants. This stuff is very slippery and cakes under your shoe soles like wet snow. It builds up to about an inch if moist, as the L&C men also experienced while pulling their boats along the riverbank.

Why I did not see the Rockies

I made it down fine and cooled off in the river, which was still only 60 degrees and only shoulder deep, before the thunderstorm hit. It was a doozie, like most weather systems in this area at this time. But I was all set up and had everything tied down. I even put a tarp over everything inside the tent, because all tents leak under extreme conditions.

HOMESTEADING, ANYBODY?

There was one other stop on the way to Cow Island, which I really enjoyed. I had read so much about the early hardy homesteaders on the bottomland along the river bends. It is hard to imagine how they could possibly eke out a living in this harsh, arid land. I had to check out at least one of those homesteads, and the log cabins along Cabin Rapid (#113.5) looked inviting. There was a main house with two rooms.

Nancy would love it

One was the living area with kitchen, the other was the bedroom. There were cabinets with doors half open, and the bedroom had a real white metal bed in it. I could fix this place up, I thought to myself. Nancy would love it. There even was a root cellar and an underground icehouse deep in the little hill under the flagpole. (Or was it a shelter, a hiding place from intruders?) A bit further up the gentle slope there were a few smaller log cabins and a larger barn-like structure. The brothers Ervin and Arnold Smith are supposed to have lived here as late as 1922-29, growing corn and alfalfa for raising hogs. I better ask Nancy first before I make a down payment on my retirement home.

Nights were still in the low forties, the river in the low sixties and the daytime air in the low eighties, and only one more day on the river. And it rained again, and I had a hard time getting motivated to get to my take-out at the #191 bridge. I was in Gore-Tex again, packing my wet gear into my boat, having a real hard time not slipping on that awfully slippery mud. Once in the boat, I had to scrape the mud off my Teva bottoms, but I was off without a single bad word, like all other serious river travelers before me. No complaints; this is the way it is here at this time of year.

THE LAST DAYS OF THE NEZ PERCE INDIAN TRIBE

I soon came to the Nez Perce National Historic Trail on which Indian Chief Joseph led his people towards freedom in Canada, trying to avoid a conflict with the American army. But on Oct. 5, 1877, just 45 miles short of their goal, the entire tribe was intercepted and nearly eradicated. The Chief’s surrender speech, “I am tired of fighting”, is one of the most moving pieces I have read in a long time. The somber mood of this gray rainy morning seemed like a fair expression of this sad chapter in America’s history.

I paddled on mechanically, overcome by the many conflicting strands of history which wove eager explorers, early settlers and homesteaders, boat men and railroaders into the native fabric which had existed here for thousands of years, and all this against a backdrop of a more or less violent geological past of 80 million years or more.

To a certain extent this stretch of the Upper Missouri River is a time capsule; not much has changed since the L&C days or the first sketches by Bodmer. Our modern civilization with its towns and industry has passed this area by, except for a few bottomland farms and homesteads. But the sandstone is soft and will erode with each passing year. The walls will collapse; the white columns with their parapets will tumble and end up as silt and mud in the river.

Time will not stand still; it only seems that way. Looking at the scenery at Eagle Creek seemed like “a momentary stay beyond confusion” (R. Frost), as if you were staring “at the still point of the turning world” (T.S. Eliot), a scene where time stands still for a moment, but only to flow on. Nature will inevitably do its thing, and whatever that is, it will still be spectacular in this particular region.

In 1884 the Montana gold rush hit this area for a short while. A huge coal-fired power plant was erected at river mile 134.1. But that boom too has ended, and nothing is left of the eight tall smoke stacks or the mine itself - only new cottonwood trees, sage and other shrubs.

END OF TRIP

Before I realized it, the bridge at James Kipp State Park came into view and with it, the end of my trip. I noted that I had missed the big bicentennial L&C celebration here by one day. Tough luck! Only a string of white canvas Indian wigwams and trampled grass were left near my little designated camping area. Fishermen were back, frantically trying to snare 50-100 pound plankton-eating paddlefish (an ancient fish near extinction) with a one-week season and a special lottery-based permit.

I had missed the party

I also realized that this is the beginning of the powerboat area extending into the 150-mile long reservoir created by the Fort Peck Dam, a major recreation area for power boaters. It was time for me to get off the river.

My ride arrived right on time at 9:00 a.m. the next day and took me, boat and all, through endless prairie land filled with pronghorn antelopes, past the little town of Lewistown (where I quickly mailed my two paddles back to Maine), to a Great Falls airport hotel, from whence I would catch an early flight back to Maine the next morning.

Great planning, I thought to myself, especially when I checked the national weather report, warning of a severe hail and rainstorm with 60 knot winds in about an hour from now. I was glad I was in a hotel, because it was as fierce as predicted. That storm would have tested me and my gear for sure, and I was glad I was not out there. Instead I ordered a hefty prairie-raised steak with all the fixings, and even ordered a celebratory glass of wine to wash it down properly.

All in all, a very memorable, fascinating, wild and very scenic river trip, which I enjoyed immensely, despite the cold nights and water, the frequent rains and often strong winds, as well as the desolate and lonely landscape. But since L&C did it this time of year, you should too, to get as close as possible to what it must have been like for the intrepid Corps of Discovery some 200 years ago on their way to the Pacific and back. Hats off to the explorers! It was truly a great feat all around - I am still very impressed.

****************

INFO:

4 river maps with info issued by: Bureau of Land Management, Lewistown District, Airport Rd., P.O. Box 1160, Lewistown, MT 59457-1160

Reference book on L&C as well as geological and other pertinent river info: Glenn Monahan & Chandler Biggs: Montana’s Wild & Scenic Upper Missouri River. Northern Rocky Mountains Book, Anaconda, MT , 1997/2001. (purchased through Montana River Outfitters)

Boat rental and car shuttle through: Montana River Outfitters, Great Falls, MT (craigm@montana.com)

Equipment used: 16’ OLD TOWN Penobscot (paddled from bow seat, stern first)

Zaveral carbon fiber bent-shaft paddles (personal; mailed in shipping carton via U.S. Postal Service Priority Mail)

Iridium Satellite phone (personal)

Marine Radio Telephone for weather reports (useless on the river; out of range)

© Reinhard Zollitsch

BACK TO TOP OF PAGE