CELEBRATING QUÉBEC'S 400TH BIRTHDAY

May 2007

By Reinhard Zollitsch

I have always enjoyed reading Robert McCloskey's books about the Maine coast to my four kids, as well as Holling Clancy Holling's classic Paddle-to-the-Sea, among many others. I just became a double grandfather and thought how nice it would be if I could add a personal note to those seafaring, coastal, boaty books. I already visualize myself looking into those wide-open, dreamy eyes of my young audience, and while gently closing each book hear myself quietly adding “You know, I have been there too in a tiny little boat just like this one here.”

Down the mighty St. Lawrence

As far as the mighty St. Lawrence River is concerned, there were actually two very good reasons for me to finally tackle the 350 miles from the last of the Great Lakes (Lake Ontario) to Québec city:

- This stretch had eluded me in 1999 on my journey from Lake Champlain around the Gaspé peninsula back to New Brunswick and the Baie de Chaleur. I felt I had to do this upper stretch of the St. Lawrence so I could finally say I had paddled the entire river from the Great Lakes to the sea, as in the children's book mentioned above.

- But the real reason for doing the trip this year, in May 2007, was the fact that the city of Québec was getting ready to celebrate its 400th birthday. In 1608 Samuel de Champlain had built a very modest settlement on Cap Diamand (Cape Diamond), where today's downtown, Le Citadelle and the famous hotel, the Chateau Frontenac, are located.

May would also be a good time to be on that big river, I thought. I would beat the boat traffic and tourists in the Thousand Island segment, as well as the black fly and mosquito season, and find plenty of water to flush me downstream towards my goal.

Paddle to the Sea, then and now

From my 1999 trip I knew that the St. Lawrence was huge and intricate to navigate and that it was a major shipping route for large container ships and equally huge Great Lakes bulk carriers, throwing significant wakes. But the major obstacles for a small boat like mine were the seven big locks, which would not allow any "motorless boat smaller than 20 feet, weighing less than 900 kilos" in the locks.

I could not believe the info websites of the St. Lawrence Seaway, but numerous e-mails as well as phone calls confirmed my suspicion: they really meant it, no exception - “Non!!!” And that after my previous wonderful experiences in the Champlain, Canso Strait and Chambly canals, most of which were very accommodating and courteous to small boaters and did not even cost me a penny.

Did that mean one could not “paddle to the sea” any more in traditional man-powered crafts like a canoe or sea kayak, and that on the "Canada River", as the St. Lawrence was known for a long time, in a craft synonymous with Canada, a canoe, a "Canadian”, as this type of boat is known world wide"? I was shocked. That could not be! “Non!!!”

I know from my home state, Maine, for example, that when a power plant dams a river, they are responsible for supplying a portage trail or even a car shuttle around their man-made structure. The St. Lawrence Seaway people, on the other hand, sounded annoyed when I pressed the point, downright hostile, except for one person at the US office at the Eisenhower/Snell locks.

I desperately needed a plan B or even C to pull off my trip, because I was going to paddle to the sea, no matter what, especially when I get challenged.

So before I left on my trip I had arranged various ways to get through or around those big 233.5 by 24.4 meter (766 by 80 feet) large “boxes” that could lower big 25,000 metric ton freighters down about 10 meters (30 feet) each time in 7-10 minutes. (How do you like all those numbers?)

Planning this was definitely the hardest and most frustrating part of my entire trip, but it was necessary to guarantee a smooth, hassle-free trip, and in the end was worth my effort. So, if anybody else is planning to go down the upper St. Lawrence River, don't leave home unless you have a definite plan of action. Portaging boat and gear through big cities or towns is no option, since you will lose at least half of your gear to eager “takers” – it has happened to several paddlers (who should have known better), who then complained about it in their articles or books.

The trip begins

May 16, 2007 was approaching, everything was as set as possible, and I even had arranged for a ride to St. Vincent, NY (600 miles from Orono, ME) and a pick-up in Québec City (250 miles from Orono, ME) for May 31. Thank you, merci, danke, Nancy. You are wonderful!

Put-in at Tibbett's Light on the edge of Lake Ontario

In the early morning of May 18 I put in at the Tibbett's Point Lighthouse at the very tip of Cape Vincent, NY. The shore was rocky, not ideal for loading a boat, and a strong head wind greeted me as soon as I pushed off. I was only disappointed that I had misplaced my stopwatch, since I still navigate by dead reckoning. So my wristwatch would have to do.

I had set myself up with a daily goal of 25 miles, which would mean I would get to Québec in 14 days or two weeks exactly, 1:00 pm, to be specific. “Why don't you get us a nice room for the night, before we drive home the next day”, I had told Nancy, and she did – and wait till you hear what she got us.

I had ordered a full set of 18”X24” nautical charts (less expensive black and white reprints of the standard NOAA charts from a chart supplier in Bellingham, WA), which fit my chart case beautifully and proved to be absolutely necessary for the St. Lawrence, which is a truly big river, choked with islands and rocky shoals and multiple channels. (I was comparing notes with another paddler planning to go down parts of the St. Lawrence a few weeks later. She planned to use a colorful fishing map – good luck!)

Headed NE, right into the wind

My course for almost the entire trip was northeast, 45 degrees true, or about 60 degrees magnetic, on my compass. I had planned to follow the New York shore till about Massena/Cornwall, where I would enter Canadian waters. As instructed in Cape Vincent, NY, I would call a certain Canadian immigration phone number from the first Canadian marina I got to, to legally enter Canada. The current was slight to negligible and did not seem to compensate me for the steady north to northeast headwinds that blew till and including my last day on the water. That day, I had to wait for three hours for the wind to drop from 45 knots to a barely manageable 15-25.

International Bridge across the American Narrows, 1000 Islands

Following the south shore, the American side

The first two days took me through the Thousand Islands area, scenically a very pretty and promising area for weekend boaters. But New York residents found this vacationland a long time ago and have bought up every last foot of shoreline, including all islands and rocks, and have built summer homes, estates, even castles, on them, as on Heart Island.

It reminded me of the shoreline of Connecticut, Rhode Island and Massachusetts, on my 2005 canoe trip back from New York City to Boston. I do not appreciate or admire that type of developed shoreline and just kept on paddling. I pitched my little tent in the most out of the way corner of two just opening state parks and was not even noticed, except by some Canada geese, which were already trailing their fluffy, yellow offspring behind.

Big freighters in a narrow channel

Weatherwise, the first two nights were extremely cold, setting record lows for the dates - in the 30s. (On our drive to the put-in, we even encountered a snowstorm in the Lake Placid area on May 17.) Later in my trip, the temperatures reached record highs in the 90s. Fortunately, I am used to weather extremes and do not let them affect my trip.

1000 Islands "home"

At Morristown the vacationland aura abruptly stopped and was replaced with old dilapidated remnants of the industrial period – old piers and factories and tenement buildings. The current also suddenly picked up on the stretch to the Iroquois dam and lock; so did the headwind, and I suddenly felt very cold and lonely. I took shelter on Toussaint Island, had some hot chocolate and left negotiating the dam for the next day.

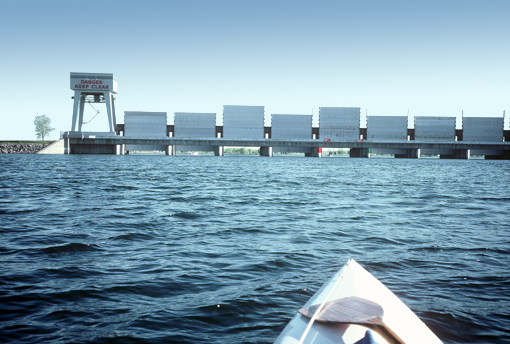

Running the flood gate in a dam

My charts told me that small boaters could run the control dam through gate #28 downstream or through gate #30 upstream. I could hardly believe that. I googled this place through “MapQuest”, and got a great aerial view of the dam. I counted the gates, and yes, #28 was the fifth gate from the left and had a clearance of about 8' (I had to take their word for it).

The third gate from the left was gate #30, the upstream gate. But how much of a drop was there? How violently would it flow? It couldn't be more than 7 or 8 knots because if it was, no small pleasure craft or fishing boat would make it upstream. That thought convinced me that I could do it too – just stay in the middle and be ready for a low brace, I told myself. I tried to hail the lockmaster on my VHF radio to inform him about my plan, but he must have “stepped out for a moment”.

Iroquois control dam: 5th gate from the left down, 3rd one upstream

And I felt great doing it all on my own, approaching slowly, carefully, looking through the gates to see how much the water level would drop. Then I saw a fishing boat below the dam, almost on my level, and I went for it – and it was a cinch. And just think: no portage, no locks, no fuss – my kind of dam.

I then figured that the dam was only here to guarantee water in the dry season later in the year, when the upstream Galop Island rapids would run dry if water wasn't held back. This time of year the river was flowing through the dam almost unimpeded. I then wondered whether the big boats would still have to be locked through or could also steam through the locks, ever so slowly, without stopping, but I doubted it.

Trouble in the locks

The following day took me to the next big obstacle, the U.S. Eisenhower and Snell locks. I had planned to check out the spillway dam a tad north of the canal in Robert Moses State Park, to see whether I could portage it and take care of the two locks with one "short" carry to the road across the dam, and then slide my loaded boat down a long but gradual grassy slope back into the river.

Well, the take-out was through trees and over a rock bank, but worst of all, the downslope was endless, dropping almost 150 feet, terminating in a steep drop over huge boulders, an ankle breaker. I tried the marina on the other side for help, but: "Sorry, we are closed". I got back in my boat, and decided to pitch my tent in a spot I had seen on the way up to this spillway dam and think about it some more. I also needed food.

I had to try plan C the next day, i.e. paddle to the locks and remind them that I had gotten a verbal OK from their head office to raft up with another pleasure craft, so that I would be allowed in the locks. The crews were very reluctant to let me in, even tied up alongside a sailboat whose home port happened to be Lübeck, Germany, a few miles away from where I had grown up. Thanks, Andreas and Sabine! They were extremely helpful, but not so the lock staff. They ordered me out of my boat onto the sailboat and to stay there till we were through both locks.

Entering Eisenhower/Snell locks

Between the two locks a service tugboat was shadowing us and then decided to pass us at full speed on our port side where my boat was rafted up. What was the skipper thinking? There was no emergency he had to attend to. He was just having fun harassing us, hoping to see my boat fill with water and roll over, and bang against the side of the sailboat.

He was obviously out to prove his point that small motorless boats do not belong in the shipping locks and canal. I was upset, to put it mildly, but saw it coming in time, and felt challenged to thwart his aggression and have the last laugh. I quickly adjusted my stern line and hand-held the bow line of my boat so I could coax and manhandle my boat over the huge wake and keep it from slamming against the sailboat.

It was most despicable and unseaman-like behavior on the part of the tugboat skipper - obvious chicanery. But I just smiled back at him like a Cheshire cat – our boats were that close - since I knew I could handle the situation with my type of boat and win the contest.

I could have yelled, reminding him that powerboats are responsible for their wake, but I was just glad to get out of there. It took an endless 4 hours 15 minutes for me to get through the two locks (a total of 3.5 miles). They were the most unhelpful staff and crew I have ever met on any seaway anywhere, and I used to work on freighters in Europe. By the way, the sailboat and I each had to pay $60 for the two locks - which both of us considered highway robbery, especially considering the treatment we got. Shame on you guys!

I then had to put my head down to get to my 25-mile-marker for the day, which I eventually did. By then it was 5:00 pm. and I had to stop anyway and call Nancy via satellite phone, our predetermined contact time. The small beach and bath-towel-sized grassy patch behind it on Clarke Island suddenly looked like an inviting overnight spot, and I stayed.

Crossing Lake St. Francis to Beauharnois, Canada

Every day is full of new challenges, and the next one was no exception. First there was big Lac St. Francois (St. Francis Lake) which I had to cross; it took me two hours. In the early afternoon I arrived at the marina in Salaberry-de-Valleyfield, just before the next two locks and huge dams in French-speaking Québec province.

When I phoned the Beauharnois locks before the start of my trip, their response was a very uncompromising and emphatic one-word answer: "NON!!!" That was clear enough and ended our conversation, even though I had worked out and mouthed a number of great sentences in my best high school French ahead of time.

With that attitude, I moved right on to plan B. I contacted the closest marina at Salaberry-de-Valleyfield and met a very accommodating harbormaster. He assured me he would car-shuttle me around the locks from his place to the nearest ramp below the dams/locks - no problem. Thanks for your positive and helpful attitude, Michel. You are a gem.

After my mandatory call to the Canadian immigration office to check into the country legally, I transferred my gear to the trunk of his little Honda, put the boat on a couple of life jackets on top of his roof and tied down the entire shebang to the car roof through the open door frames with a couple of docking lines he came up with. It worked, and I arrived at the ramp in Beauharnois at 5:00 pm - time to call home, and also time to stay for the night.

A big power boat on a trailer at that public boat launch provided some visual shelter from nosy officials, and I stayed. However, while I was dozing off in the early evening hours, a band of young male teenagers cruised by, talking, shouting and cussing loudly in French. They returned a bit later, while I had already entered dreamland, and they threw an 18 inch 2X4, then a car mudguard and finally a hefty brick-sized rock on top of my tent.

Each time it sounded like an explosion, and I did not know what had happened. I finally came to and figured things out, when the big rock hit my tent rain fly, and I scared them away with a loud bear growl. Fortunately my shock-corded tent had shrugged off the bombardment, but I was deeply hurt that young kids would do something like that to a total stranger in need of sleep, and that on his 43rd wedding anniversary. (I later noticed one tent-rib was split, and there were two small holes in the back of the tent. Duct tape took care of it.)

Projectiles at my Beauharnois overnight

By the way, the same thing happened to me again the next night in Longueuil, just on the other side of Montreal. Another big rock landed on my tent and my paddles inside. It was definitely time for me to get out of populated areas.

Lake St. Louis and the Lachine Rapids in Montreal

Sunrise next morning saw me back in my saddle again, traversing big Lac Saint Louis towards Montreal and the infamous Lachine Rapids. Just as I was about to cross over to Isle Doral and the entrance to the old Lachine canal, my sailing friends from Lübeck crossed my bow, about to enter the Canal de la Rive Sud, the big ship's canal, but I doubt whether they saw me, since they could not possibly have expected me there.

I then noticed the increased pull of the beginning of the rapids and made sure I made it across in good time. These were the rapids that all early explorers like Cartier and Champlain encountered, thinking that China would be on the other side of this "Northwest Passage", the "Canada River" (therefore the name "China Rapids").

Early seafaring explorers were obsessed with the search for a seaway from Europe to the Orient. Even Henry Hudson thought he had found the passage, when he sailed up the tidal Hudson River in 1609, till he got to the rock ledges north of today's Troy, NY. Columbus, as we all know, did not even know there was an extra (American) continent between his 1492 landing spot in the "West Indies" and the "land of riches", the Orient.

The “growth” of the American continent from nothing to a very thin affair (the size of Florida) and eventually to a significant continent in the days of the Lewis and Clark expedition from the Mississippi to the Pacific in 1804-06, had always fascinated me, and I absolutely had to see and hopefully even be on these historic "Lachine Rapids". But how? Who is out on those rapids? Only big rafts or jet boats could handle them.

That was it. I googled the problem and found two jet boat outfitters who run the rapids. I chose the company at the head of the big rapids rather than the one which starts its trips from the Old Port in downtown Montreal. And again, I got a most encouraging and helpful e-mail back from the owner, Davide. Thanks, my man!

I carefully drifted down under the first two bridges to his place on Lasalle Blvd. and 75th Ave., just under the first high-tension wire crossing the river, and there he was, about to have lunch with his eager group of young raft guides. He gave me a quick tour of the big drop, "Big John", named after “Big John Le Canadien”, a Mohawk native from nearby Kahnawake who used to guide steamships down the rapids quite some years ago.

The drop is right in the middle of the stretch between Lasalle proper and Heron Island. This is also the place where the canoeists Louis and his native guide drowned during one of Champlain's earlier visits. I tried to block out that last tidbit of information, while looking for a sneak way along shore to get down this stretch, but I could not find any safe way because of the power station water intake there, and opted for a swift piggyback on the jet boat.

Davide's cheerful crew jet-boating me through "Big John"

And the drop was BIG, REAL BIG, as the jet boat slammed into a train of humongous standing waves, getting us all wet and bouncing my loaded boat, which we had put on top of the backrests of the empty passenger seats, on life jackets to soften the bounce. The Kevlar expedition lay-up of my boat came in handy, also when we tried to ease it back into the water below the last ledge drop. "C'est ca!", Davide pronounced. "This is it, you can handle it from here on.”

Unloading a full boat over the side in the middle of a river, making sure the boat does not get sucked back into the rapids, is not as easy as sliding it on top of the railings from a steady dock. Suffice it to say, we managed to angle the boat back into the St. Lawrence and me into the boat...and I was off again, with a big smile and a big thank-you.

Yee-ha! Hitting "Big John"

The whole operation was done in no time. I found myself in the middle of the river, or better "Le Basin", the basin, eager to hold on to the left shore again, which I had studied on my nautical charts. I had to go to the left of Isle Des Soeurs under the Champlain bridge, in order to avoid the big "ice control structure" across the wider right river arm, and eventually go under the Victoria bridge and tackle the Saint Normand rapids. Suddenly the current picked up noticeably; my chart indicated 6 knots, and rapids with rocky drops. But I was sharp and in a great “good-aggressive” mood and felt I had to prove Davide right.

I made it fine through the ledge drops, but only half-heartedly tried to swing into the Old Port to see more of the downtown city. But the current blew me by it, and I smiled as I went with the flow under the Cartier bridge, and along Isle Saint Helene with its huge amusement park with giant roller coaster. At the tip of the last island, I crossed over to the right shore, including the entrance to the Canal de la Rive Sud, to the Cap-sur-Mer in Longueuil. The same big freighter came out of the locks that I had seen enter the canal when I crossed over to Lachine. I did not give it much thought, though; I needed a break.

Then I noticed with a smile that I had already paddled my 25 miles for the day, and it was only 2:00 pm. I found a nice black sandy/gravelly beach to pitch my tent on, and I enjoyed the afternoon with coffee and cocoa much more than the previous two.

I had just moved into my tent to settle things there when I noticed my sailing friends from Lübeck exit the canal. Not until then did it dawn on me that I had paddled through and around Lachine Rapids one hour faster than a boat can go around them through the canal and two locks. What an amazing thought. And no more locks and dams from here to Québec! I felt buoyed. However, that evening I (in my little tent) was bombarded with yet another brick-sized rock - how nasty and totally uncalled-for.

City haze over Montreal

Back on the River again

Up again at 6:00 and off by 7:30, back on 60 magnetic, more big islands in the middle of the river, and many arms to choose from. I had lunch at the big cathedral in the little town of Varennes, visible for miles in its shiny metallic glory. Many of the larger islands must have been used for communal grazing or haying and often still indicate that use by name (Isle de la Commune). I in turn enjoyed the graininess of my one piece of 12-grain bread, the crunch of my carrot and the fruity sweetness of my small dish of Mott's applesauce, my typical lunch.

I then took a channel behind a long string of islands off the small town of Contrecoeur, hoping to find a small grassy spot for my tent. However, all islands were a pristine wildlife preserve, so beautiful, that I could not bring myself to sully the vista, not even with my little minimal tent. I eventually found a small spot near shore on the town side, where I was not noticed. I had paddled the 27 miles in 6 hours 45 minutes, a typical day.

How wonderful, I thought to myself, picturing me living here in this little town. Their view to the river was absolutely "clean" - there was not a single house or shed or man-made structure in sight, just wonderful, original, untouched nature. How unlike the "pretty", touristy, 1,000-Island stretch, choked with vacation homes, motels etc. How forethoughted the city fathers (and mothers) must have been, not to allow anybody to buy up the islands and “develop” them. Congratulations! What a modern, ecological thing to do. You were so much ahead of your times. I am impressed.

As I wrote those thoughts down in my trip log, a powerful thunderstorm went by with a fierce windstorm, blinding lightning and instant, earsplitting thunder - that was close!

Closing the gap

Next day would be significant, since I would cross my path from my 1999 trip near Sorel. This time, though, I had planned to paddle along the north shore all the way to Québec (instead of the south shore). I would follow a thin river arm around the nightmarish jumble of islands between Sorel and 20-mile long (and 9-mile wide) Lac St. Pierre, towards Berthierville and the last island, Isle à l'Aigle, Eagle Island.

It was a very convenient stop, a tad muddy and wet underfoot, but a great jump-off spot for next day's long hop across the lake towards Trois Rivières. I started an hour earlier to take advantage of the calmer morning hours and to avoid the rains predicted for the early afternoon. I had barely put up my tent in my designated spot at the mouth of the Sable River, when the rain started. That was OK by me. I was on a wide sand beach under a tall poplar tree, enjoying my coffee as well as some fun reading and writing my trip log. Tomorrow looked easy: back on the river towards Québec.

Big Lac St. Pierre

The home stretch

But the wind was howling when I packed my gear in the morning, and my corner of the lake was filled with whitecaps and streamers, sporting a good set of surf waves on my beach. It meant I had to set up and time things right if I did not want to get swamped before I could close the spray skirt and get into deeper water. I got slapped occasionally by a wave-top, but my Gore-Tex jacket kept me dry, i.e. warm in my own sweaty mist. The wind came over my right quarter (SSW, 15-25), and I was glad I had a good rudder to help me out with my paddling.

Trois Rivière Bridge

At the St. Maurice River at Trois Rivières I pulled out for half an hour to let the front pass through - a wall of black clouds with corkscrews hanging from its forward edge. But the river got big again, three miles across, and the SSW wind had a very long fetch. I was working hard to stay upright and dry.

I finally pulled out behind the breakwater of the small town of Champlain, where I found a tiny spot of sand above high tide mark, but the tides were still minimal that far up the river. I felt I had to stop here, being a real fan of Samuel, but also because it was easy for me to reach shore. From here to Québec, both shores shoal significantly, with hard rock flats (“battures”) rather than the usual sand banks or mud flats.

I went into town and asked several people about the significance of the town's name. What did Samuel de Champlain do here, and on what trip was it? Nobody knew any history; not even the church plaza gave away the secret of the town's name. It must have been just a good name that no other town had claimed.

Champlain certainly went by here in 1609 on his way to the Richelieu River (the Iroquois River, as it was known then) and Lake Champlain. He also passed by here a few years later on his way to Hochelaga/Montreal on the Lachine Rapids, from where his quest to find the Great Lakes continued up the Ottawa River. (Champlain saw Georgian Bay, the northeastern part of Lake Huron, and Lake Ontario for sure.)

Two more stops for me: Saint Charles-Des-Grondines, where I first noticed the significant tides on the St. Lawrence; and Neuville. I had set up for the night in Grondines, when at 8:00 pm the tide came up to my doorstep and looked as if it would visit me in my tent. And since I could not move back or to a higher place at that spot, I quickly broke camp and paddled down to the town's breakwater, where I found some level grass in one corner and some rest one hour later. Thanks, I needed that.

Neuville was my last stop on the river. It was a very gray, dank and foggy day, 25 miles down the swift Richelieu Rips, around a rare 90 degree bend in the river at the steep, bluish-black slate shores of Pointe-de-Platon, and on past Donnacona to the small town of Neuville.

I again pulled out near the breakwater, to make sure I would not be stranded by the now significant tides in the morning. I was tucked away behind some empty boat trailers, which began to whistle and howl as the wind picked up. It rose to 45 knots and kept up all night. I was sure the morning would be better, since it was going to be my last day on the river, and Nancy was on her way from Orono, Maine to pick me up at the Québec-Lévis ferry terminal at 1:00 pm. The weather channel predicted NE10, but not 45 knots, and I still had 21 more miles to paddle. So it had to get better.

A stormy last day on the river

I dutifully packed up, hoping the wind would suddenly abate and allow me to be on my way. I was very skeptical, though, since I could clearly see what happens when a strong wind runs counter to the tidal flow. The river was white, big waves were breaking everywhere, and the tops were even being blown off. It looked fierce, but I stuck my bow around the breakwater, only to duck back into the marina harbor. It was impossible to make headway, and it was downright dangerous. No time to be out there.

So I pulled out at the boat ramp and waited one hour, then two and even three hours. Between hitching my boat back towards the receding water, I warmed up in the clubhouse with a cup of hot coffee. Thanks, Raphael! I also was able to leave Nancy a message saying I would be majorly delayed, 2-3 hours.

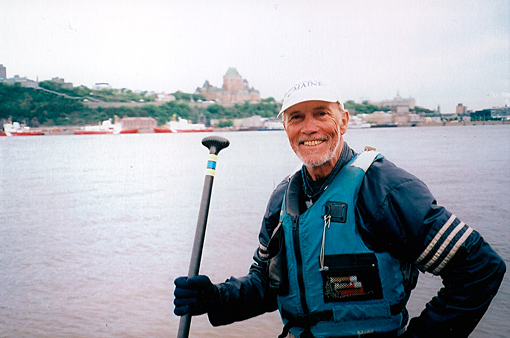

Dual bridges at Québec City

At 10:30 am the wind had abated somewhat, to around 15-25 knots, and I was off, with grim determination and under full racing power. I felt I had to make it to our rendezvous before nightfall. I had one 10-minute lunch break and covered the 21 miles in exactly 5 hours. I was spent, but feeling immensely accomplished that I had made it to Lévis/Québec at all, and was extremely happy to see Nancy at the right place and cheerful as ever. What a girl! Thanks my dear – and tell me, where are we staying for the night?

I needed a soft and level bed after today and the past 14 nights camped along the banks of the mighty St. Lawrence. Without saying anything, she turned around, pointing to the biggest and most splendiferous hotel of Québec, sitting right on top of Champlain's first fort and settlement of 1608 – the Chateau Frontenac. How appropriate, how wonderful, and since I had not spent a cent for 14 overnights on my entire trip, how affordable to spend it all in one lovely night on the seventh floor, looking out over the copper-sheathed rooftops and down onto the mighty river on which I had just come for 350 miles to celebrate the city's 400th birthday.

Take-out at Lévis/Québec

Celebrating Québec's 400th birthday in the Chateau Frontenac

A lovely dinner in-house with an appropriately named glass of beer (La Fin Du Monde, The End of the World) completed the evening; I fell into bed and drifted off into lala-land in no time. The last images I remembered were facets of my 1999-2003 trips in my little boat, drifting on towards the Gaspé, through the Gulf of St. Lawrence, around New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island, and eventually through the Strait of Canso into the open Atlantic, just as the little wooden boat had done in the book Paddle to the Sea. I now had done it too ...

View from my "humble abode"

What a trip, what a river, what an adventure! I enjoyed myself immensely, even at age 68. And I was delighted to see Québec gearing up for the big event, the big 400-year birthday party in 2008: the boardwalk was being repaired, and even the huge statue of Champlain was being cleaned up and refurbished for the big occasion.

Champlain getting a makeover for the big party

Salut to Samuel de Champlain

and the hardy first 28 settlers of 1608, of which only 8 survived the first harsh winter, I am sorry to say. But this here is the cradle of today's 18 million North Americans of French descent. Salut to the City of Québec and its deeply rooted French culture and language. And salut to the mighty St. Lawrence, the Canada River.

******************

INFO:

For author's bio and previous trip reports, see: http://www.zollitschcanoeadventures.com

Boat and gear: Covered 17'2” Kruger SEA WIND sea canoe with rudder and spray skirt, see: http://www.krugercanoes.com

Lensatic radar reflector from West Marine, and bicycle wiggle stick (both to enhance visibility)

Camping gear and all food for 14 days; two 2.5 gal. water containers

NOAA charts for the entire river, 18”X24” black & white copies from Bellingham Chart Printers Division (Tides End Ltd.): http://www.tidesend.com

Road maps and aerial views of specific areas: http://www.mapquest.com

St. Lawrence Seaway info: http://www.greatlakes-seaway.com

NY State Parks (1000 Islands) info: http://www.nysparks.state.ny.us/regions/thousandis.asp

Jet Boat rides on the Lachine Rapids: http://www.RaftingMontreal.com (Les Descentes sur le St. Laurent); (ask for Davide)

H.P. Biggar (ed): The Works of Samuel de Champlain. Vol. I, Toronto, 1922.

W. Goetsmann/G. Williams: The Atlas of North American Exploration. Swanson Publ. Ltd, 1992.

Janice Hamilton: The St. Lawrence River. Price-Patterson Ltd., Montreal, 2006.

Holling Clancy Holling: Paddle-to-the-Sea. Houghton Mifflin Co., Boston/New York, 1941/1969.

Robert McCloskey: One Morning in Maine. Viking Penguin Inc, 1952/1980.

Time of Wonder. Viking Penguin Inc,1957/1985.

Burt Dow, Deep-Water Man. The Viking Press, Inc, 1963.

© Reinhard Zollitsch

BACK TO TOP OF PAGE