Around Novia Scotia by Sea Canoe

Part 1: Port Elgin to Halifax

By Reinhard Zollitsch

August 2003

The Plan

I had been thinking about paddling in Nova Scotia for a long time, but I somehow always went somewhere else in the Maritimes instead. I canoed around Prince Edward Island, followed the shores of New Brunswick, and even went around the Gaspé peninsula, but never made the jump across the Bay of Fundy from St. John to Digby, or from Bar Harbor to Yarmouth with the super fast CAT. Either ferry could have gotten me there in a couple of hours. I even have good friends in Wolfville, whom I should have visited years ago, but it wasn’t till this summer, August to be exact, that I finally decided to do some serious paddling in Nova Scotia.

Ever since my horrific sailing experience off Nova Scotia in 1977, I have been shying away from that province. Enduring two days of 60 knot winds near Sable Island must have left an indelible impression on my mind, that would not go away till I finally wrote down the events of that trans-Atlantic voyage 25 years later. (See Messing about in Boats, July 15, 2003)

In previous years I had paddled to Port Elgin, New Brunswick, right on the border with Nova Scotia, so it was obvious for me where I would start my Scotia venture. I would follow the North Shore for almost 200 miles, almost due east, to the Strait of Canso, separating Nova Scotia proper from Cape Breton Island, and swing around Cape Canso on the Atlantic to Halifax in a clockwise rotation for another 250 miles. I knew that 450 miles (720 km) solo would be a significant stretch for 18 plus days, but not much longer than last year’s trip on the German Baltic.

My 17’2” Verlen Kruger Sea Wind sea canoe could handle all the supplies for such a trip, plus 5.5 gallons of water to be refilled in two ports, and I felt pretty confident that I could pull off another long trip like that.

Nancy again sweetly agreed to car shuttle me to Port Elgin and pick me up in Halifax afterwards. I felt very lucky, as with all my previous long distance trips - Thanks, Nancy. So on August 9, 2003 we drove the 325 miles from Orono, Maine to Port Elgin and checked into the little motel near the lighthouse and fort at the mouth of the Gaspereaux River, my put-in point.

Fog, Rain and a Heavy Boat

Loading the boat the next morning was easy, since the high tide came right up to the road. But then I had to follow a compass course across Baie Verte to Tidnish Point, a good 3 miles away, because thick fog had settled in the bay and it was raining. A wet hug and a kiss good-bye, and I was off in my Gore-Tex suit and floppy hat - a typical send-off. I promised to call Nancy each evening at 6:00 p.m. (Nova Scotia time) on my satellite phone, so that I would not worry that she would worry about me being out there all by myself.

It did clear eventually so I could follow the shoreline around Coldspring Head and Lewis Head into incredibly shallow Pugwash Bay. I had picked Bergeman Point at the tip of a peninsula sticking into the middle of the bay, since it looked like the only deep spot to land at. By now it was low tide, and my energy was also ebbing. But I spotted a more or less level area on the sea wall for my tent and started portaging.

Off to make friends with Nova Scotia

The first three days of a trip are always the hardest for me. The boat is at its heaviest with all the supplies for 21 days plus 5.5 gallons of water, and, being a pencil pusher by profession, I am not quite used to heavy lifting. To boot, I had to hustle my gear at low tide over a slippery boulder field to the sea wall. When it came to carrying the boat up, I was so spent I could barely lift the boat. I was devastated.

I had to get it up there; it was low tide. Were age (64) and arthritis finally catching up with me? NO WAY! I heard this little adamant voice in me and jerked the boat up and lugged it over all those slimy rocks in one big launch to the sea wall. I almost pulled my back out in the process, which would not have been a pretty picture, but I felt I had to prove a point, and ignored the warning signs.

I huffed and I puffed, dropped the boat on a bed of seaweed and me on a big rock and decided this was it. And while I was down, I figured it was also a good time for a water break and granola bar. At that point, I noticed to my chagrin that I had left my 3-gallon water container under my seat in the canoe, adding about 25 lbs. to the 65 lbs. of the boat! I could have been mad at myself, but instead I managed a tired smile, because that meant I had not lost it after all.

There was hope for the rest of the trip, and believe me, this did not happen again. As a matter of fact, after that, I would remove absolutely everything from my boat, deck-mounted spare paddle, bailer, air horn and even the chart, and portaging the boat was never a problem again.

Next morning I started my usual trip routine: up at 6:00 a.m., off by 7:30 a.m. By then the tide was almost up to my tent and made life easy. I set my boat on driftwood rollers near the water’s edge, stowed my gear, pushed it into the water and hopped in myself.

My day started with a 2-mile crossing to Fishing Point. Then I headed straight east for about 13 miles, following a red sandstone shore that reminded me of Prince Edward Island. Except for a brand new swanky resort area with significant golf course at Cape Cliff, the shore was almost empty; only a few small houses here and there, one church, but no real settlement.

At Smith Point I had to go south for three miles, and cross two long ocean arms. The wind had settled in the westsouthwest and was suddenly whipping up whitecaps and streamers. I had to work real hard and dance the waves as they were cresting almost parallel to my boat. Most of the ledges off Oak Island and Schooner Point had lots of gray seals on them, who were checking me out with a big splash as I paddled by.

I decided to stop before Tatamagouche Bay, which would have a significant 2.5 and a 3.2-mile crossing, and pulled out on a long sand spit island around Malagesh. No slippery rocks to stumble over this time, just nice sand. Great, I thought, but the wind blew the sand all over the place. It got airborne, and I had to close my tent and sweltered as a result. I needed shade, and decided to look harder for a shady spot for my tent, come tomorrow.

The North Shore - Getting into the Routine

Cape John, with its steep red sandstone cliffs, was a welcome sight after the two crossings. It looked just like the North Shore of PEI and continued like that for about 23 miles all the way to Caribou Point, from where the ferry to Wood Islands, PEI leaves. I found a perfect little pocket beach at trip mile #88, with a steep sandstone cliff behind me casting some shade. I felt good for the first time on this trip, not exhausted, hurting or overheating, just plain good. My trip was beginning. I was adjusting to the rigors of paddling 25 miles a day and learning what not to do along this coastline.

Next morning was a paddler’s delight: sunny, calm, and warm, with the tide almost high for an easy take-off. Navigation was a bit on the tedious side, you might say: 20 miles straight to the east, but I accepted it gladly since it was easy, confidence building and pretty. There was more sandstone shoreline, with small towns, mostly summer colonies with modest houses and camps and their modern equivalents, house trailers; no developments, marinas or large noisy beaches.

It was quiet ashore and on the ocean. The lobster season was over, and there is no ground fishing in Nova Scotia, except for a few small outboard sport fishing boats with guys mostly hand lining. Otherwise the horizon was empty and the waters were unobstructed - no myriad of lobster traps as along our Maine shore to snag your rudder or grab your paddle.

Granted, those lobster buoys are pretty in their colorfulness, but a real nuisance to small boaters, including sailors, let’s face it. Fortunately, Maine requires line that sinks, made of nylon, not poly, which floats on the surface and can really do a job on your rudder or propeller. These floating lines can also be harmful to seals and whales, I hear. Nova Scotia and the Maritimes in general still allow floating poly line, and in my opinion should switch to nylon for all the above mentioned reasons.

Near Caribou Point I could see “The Island”, Prince Edward Island that is, 13 miles across Northumberland Strait, and ferry boats coming and going out of tiny Caribou Harbor. The wind had freshened as I rounded the point and was blowing from the SW. Getting into picturesque Pictou Harbor was a good work-out, but the lighthouse at the end of the mile-long sand spit looked too enticing.

I had to get there; it looked like a great stop for water and a granola bar. And it was, and a group of five sea kayakers thought so too, but the belching paper mill up the bay on Abercrombie Point was an offensive sight, and I pushed off soon to reach my goal for the day, Mackenzie Head, at the eastern end of Pictou Bay.

Rounding Cape George

7 hours for 26.5 miles, a long paddle, but a swim and later coffee on my small shady pocket beach picked up my spirits in short time. After that I usually write my trip log and prepare tomorrow’s run by reading the official Sailing Directions for this area and Scott Cunningham’s Sea Kayaking in Nova Scotia, and transfer all the pertinent information onto my Canadian charts. Tomorrow I would start the 40-mile long hitch to the northeast to the rather intimidating looking Cape George.

I should make it to the small harbor of Arisaig tomorrow, if the weather holds. Then it’s suppertime, the high point of the day. After supper is time for a quick call home and for some nonacademic fun reading, if possible something that fits into the area I am paddling in. This time it was Lone Voyager, the Blackburn story - his heroic survival row and all his later ocean voyages - as well as a mix of the intense Perfect Storm and the whimsical new book by Robb White, How to Build a Tin Canoe. Sunset occurred at about 8:00 p.m., Canadian time that is, as the tide came in again.

Another calm sunny start to the day and good progress to Merrigomish Island, which is connected to the mainland with a three-mile-long very narrow sandspit bar. Suddenly the wind breezed up from the northwest, and in no time there were breaking waves getting steeper by the minute. I considered bailing out at Bailey Brook, but did not like the sound of it and pushed on. After so many miles of beaches, I figured I could always make a safe beach landing somewhere, but I was mistaken.

The shore got steep and rocky and very inhospitable looking. I realized I had to hang in there for another 5 miles to Arisaig, which had three breakwaters. Number one and two formed the inner boat harbor, with steep concrete piers for big fishing boats to tie up to. So I aimed for the space between number two and three, which turned out to be the town swimming beach. This area was wide open to a northwest wind and the waves were crashing on the shore.

Since I had no choice, I was going to land there also. With spray skirt open and rudder up, I beached my bow, jumped out and jerked the boat out of the surf before the next wave could fill it. No problem. Some kids came over to cheer and checked out the “beached white beluga” (my canoe), then went about their business while I set up my tent and followed my afternoon routine. At the fish pier I found a trash bin and a water faucet, which made Arisaig a very useful and necessary stop for me.

I stared at tomorrow’s stretch around Cape George to South Lake for a long time, looking at every harbor and bight as well as every off shore rock or bar, because the shore looked bold and very unforgiving. It also was a major point and would have tidal currents accelerating towards the point, or worse, meeting there. I was going to be ready, physically and mentally.

A dark sky over land greeted me the next morning. The wind was light, but the sea was very confused, not just from rebounding from the steep rocky shore. It was tidal. I made it past Malignant Cove (what a bad name!) in 2.5 hours to Livingstone Cove, where I took a short breather, drained and refueled my “engine” and set out for the point rounding. The shoreline had changed drastically after Arisaig.

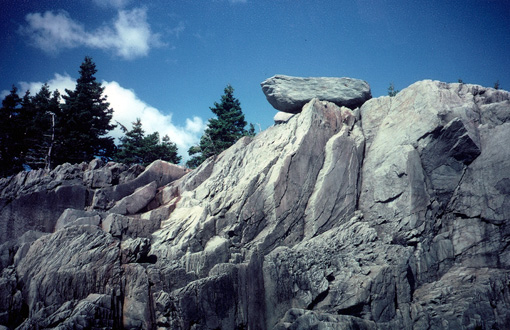

The red PEI-like sandstone was gone. Instead the shore looked rough and ragged with sharp bluish gray, hard, smooth surfaced fractured rock interlaced with white lines. After Livingstone Cove, the rock changed yet again and took on a mocha brown rounded shape and had the consistency of coarse compressed gravel. It looked very gritty, soft and geologically “young”, glacial, that is, and its shape and color reminded me of the “badlands” along the Upper Missouri River, which I had paddled earlier this year in Montana.

But enough of geology. I had to keep my eyes on the waves. The wind had picked up, and the current was very noticeable; the surface of the water looked more and more like a tufted meringue pie. I was bounding, bracing occasionally, but most importantly keeping up speed, not standing still, because in a canoe one always has one vulnerable side. I had learned years ago that it is best to paddle and brace mostly on the windward side of the canoe, which is possible with a rudder.

It’s like giving ten degrees side rudder, if you were a pilot in a small plane, to compensate for the drift or yaw. Paddling and bracing on the off-wind leeward side will trip you up sooner or later. Wind and waves will throw your boat sideways over your paddle, which inevitably will end up under your boat, with you still attached to it. Not a pretty picture.

This scenario, by the way, is still one of the most frequent causes for capsizes at sea. So learn this little trick, if you don’t already know it, and practice facing the wind and waves; don’t shy away from the spray, face it! It is not safer to turn away from the oncoming danger and paddle/brace on the “safe” side; you will not get your paddle out of the water fast enough when a wave throws you sideways, trust me! The same is true for paddling a sea kayak, of course. You need to time your strokes and not be caught paddling or bracing on the leeward side when the boat is being pushed in that direction by an oncoming wave.

Five hours into the day I rounded Cape George and to my relief found calmer seas and wind conditions on the other side. I even took pictures of the stunning mocha brown coastline, and suddenly felt very accomplished to have rounded the Cape. The remaining stretch to Canso Strait was going to be a piece of cake. But eight miles later, at # 164, South Lake, after 7:18 hours in the boat, I was “running out of gas” again and called it a day. I was still on my predetermined 25 miles per day pace and refused to feel bad about getting tired.

Cape George

Barachois and Hops

South Lake is one of the many “barachois” or “hops” along this shore, all the way to the Strait of Canso. They are small lakes, connected with the ocean through a narrow tidal gut, some navigable, others just shallow tidal inlets. Vikings used to like places like this in Europe because they provided shelter when they were in and allowed them to go out with the tide. I noticed Pictou had such a neat “harbor lake” (appropriately named Harbor Lake), and I remember lots of them along the North shore of PEI. But like any tidal estuary, those hops could also be wicked for boaters at the wrong tide, I figured.

Tomorrow would take me further south, past the large tidal inlet of Antigonish, then east, past a string of more tidal estuaries like Monk Pond, Pomquet and three large inlets around Tracadie. I would have to watch them carefully, but a flood tide is easier to traverse than an ebb tide.

Sunrise was at 6:11 a.m., right out my tent door, and I was off, in my wet clothes from yesterday. The wind was from the south, and after rounding each point I had to head right into the wind. The water looked black, streamers were forming, and it was hard work - no shortcuts or straight lining today. At Little Tracadie Harbor, I pulled out on a sea wall before the gravel bar. I had to do some landscaping before I got a five by seven spot that was level enough for my tent. The sandy beaches were gone; the shore got steeper again, more red sandstone.

The Strait of Canso

I woke up to a leaden sky and opted for Gore-Tex. I had read up on the almost 20- mile-long Strait of Canso separating Nova Scotia proper from Cape Breton Island, and its locks, the night before, and I had everything ready: my VHF marine radio was set on channel #11 to hail the lock master, my two water containers rested between my legs, and my wallet with Canadian money was in my side pocket, in case there was a lock fee. “Canso Locks, Canso Locks, this is sea canoe Sea Wind, sea canoe Sea Wind, asking permission to enter the locks from the northwest.”

Locks at Canso Strait

I mostly use my VHF radio to get the marine weather report, but do not use it much to hail other people like marinas, drawbridges, locks and the like, but I instantly got a reply:

“Sea canoe Sea Wind. I cannot see you. Stay back from the gates and I’ll open up.” Then the locks opened, one wing that is. Some water poured out. I waited a minute, then paddled into the huge 820’ long, 80’ wide and 28’ deep lock chamber. (I knew one of you readers would ask how big are the locks? So here is the answer.)

Then a curious face appeared over the left pier. It was lockmaster Harry. “Any fee?” I asked. “Nope”. “Any drinking water at the locks?” “Right here,” he answered, while handing me the hose. I was glad I was ready, because there was no way for me to get out and get the containers set up. I filled them while we talked. Harry was impressed with my stickers on the boat: “Boston - St. John” and “Around the Gaspé”, and wished me good luck for my trip around Nova Scotia to Halifax. He was a very friendly, accommodating fellow. We could have talked longer. But then the other gates opened, and when I got there, the tidal difference had already leveled off, and I was out; from the Gulf of St. Lawrence to the waters of the Atlantic in just a couple of minutes.

On Atlantic Tides - the Eastern Shore

That ended the first leg of my trip, 200 miles from Port Elgin to Canso locks. Now for the second stretch, 250 miles around Cape Canso on the open Atlantic to Halifax. I had to swallow hard. If the car shuttle had been easier, I could have stopped right here, but Halifax was so much more convenient, and I had always wanted to paddle this stretch of coastline, and so I went on. It was going to be the real challenge, and I also hoped to finally get that monkey off my back. 26 years was long enough. Watch out, here I come!

Canso Strait was like a one-mile-wide river attracting all the people with their towns, ports and industry, which were missing on my first 200-mile stretch. And where there are people, there is lots of trash and debris and civilized ugliness. All cast-offs were simply dumped over the edge into this “river”, refrigerators, stoves, car parts, concrete chunks with bent reinforcing rods sticking out of them, bricks, mortar, 2X4s and old boards, tons of blacktop and concrete lava from emptying those big cement trucks. Maybe all of this was done in part with the misguided thought of shoring up the coastline from erosion and storm damage. It looked awful and was an environmental disaster.

The greatest crime, however, as I saw it, was dismantling stunning Cape Porcupine, a 600’ high very distinct cone shaped mountain right at the causeway to Cape Breton Island. Huge machines had already gouged out the entire side of the mountain facing the Strait, and hungry conveyor belts were loading a 10,000- ton freighter with the processed rock material. I literally wept over how any country can sell their natural beauty at such a visible place.

Three miles down the Strait at Hawkesbury more yellowish looking earth materials were loaded onto huge freighters. Tall smoke stacks were belching nasty looking smoke into the sky over a mammoth tank farm. I had to get out of here and pushed on down the thoroughfare till a thunderstorm forced me ashore to put on my Gore-Tex.

The rest of the day was gray, wet, and not very uplifting, and seemed very long to the end of the Strait at Eddy Point. I always like to stop before points and headlands, to size them up for a while and hope the problem/challenge shrinks with time, and it normally does.

Big Chedabucto Bay

Chedabucto Bay is large, 45 miles around to Canso Harbor, or 16 miles across as the crow flies. But I am no crow, and Chedabucto is wide open to the east. It was going to be hard enough rounding the many shoaling points on the NW side, like Argos Shoal, Oyster Point and Ragged Head. I decided to go around this big bay and hope to make it to Cape Canso (yet another Canso!) in two days, and I did just that.

I made it fine around those one-mile shoals to Ragged Head, where I stopped for lunch. At that point I seriously considered jumping across the 4.5-mile wide bay, hoping to save myself about 7 or 8 miles. But when I got back into the boat, a wave broke into my cockpit before I could close the spray skirt. I was wet and upset with myself and decided to punish myself for this faux pas by making myself go around. And I am glad I did.

At the outflow of Guysbury Harbor the wind suddenly piped up to 20 plus knots from the southwest, and I noticed the tide had turned. My Sailing Directions mentioned a 4-5 knot tidal flow out of this large tidal basin. It was like being on a whitewater river, and I had no problem with those regular predictable waves. But I thought they would dissipate and level off. Instead they mixed with the strong wind waves from the northwest and the waves bouncing off the steep rocky shore, and I was in a dancing mode in no time. I was ready to take out and call it a day, but I couldn’t.

I had to hang in there for seven more miles to Halfway Cove. It looked as if it had an inner lobe, which should allow me to take out away from the steadily building surf. The lobe, however, was gone. It was cut off by a sand spit bar with a tiny hard running opening. So I had to prepare for a surf landing. Adrenaline was running as hard as the ebb tide, as I got myself out of the boat and the boat out of the surf without filling the cockpit. Phew, that was rough!

The night was bitterly cold, but next morning Chedabucto Bay was as calm as a millpond, and I had to reread my trip log to convince myself yesterday was real. But I was not complaining about today and made good time to Fox and Durells Island; I even dried my wet clothes.

Rounding the point into Canso Harbor, a real harbor with breakwater, piers and tank farm, a southerly breeze sprang up and worked itself up to 20 knots (I always stop guessing wind speeds at that number so as not to scare myself, but often hear later, on my weather radio, that this was another small-craft-advisory day.) I decided wisely not to go around the outside of Cape Canso, but follow the fishermen’s channel inside of Andrew Island.

It is not much of a cape anyway, I assured myself, just a pile of rocks half a mile to the east of that island. I had picked Portage Cove for my overnight spot. It was nicely protected from almost all sides, and the word portage conjured up images of a sandy beach to launch boats on. I also weighed the option of taking advantage of this portage into Dover Bay, avoiding going around the next very exposed miles to Little Dover Run, or worse, around big bad White Island with its formidable ledges to the south.

A minimal perch in Portage Cove

I checked out two arms of Portage Cove but did not find any big haul-out site, beach or portage trail. All I found was a winding little stream into a bog, too shallow for my rudder. If I had to use the portage, I would find it, I told myself, but since I hate portages, I was just as happy not finding it and being tempted in the morning to use it. Instead I found a more or less flat 5X7 foot chunk of almost white granite near deep water. I decided to pitch my tent on it. Eight bailer scoops of finer gravel took care of the cracks and crevices in the rock, and I had a very peaceful and amazingly comfortable night there. I even went swimming and noticed that the Atlantic is significantly colder than the waters on the Gulf side.

A Maze of Islands

With Canso Harbor the fun navigation was starting. I had always pictured the Atlantic coast of Nova Scotia to be more or less straight and steep, with a couple of bays, of course, but nothing like our Maine coast with its myriad of islands, ledges, deep cut bays, tidal estuaries and inside passages. How wrong I was: The Eastern shore is like Maine, only more so, but with fewer harbors, people, boats, markers and lobster buoys. I first realized that when I got my nautical charts.

After the initial gasp of “how will you ever find your way through all that with such minimal buoyage and without GPS”, I got real excited about the challenge. In a nutshell, this coastline is a sailor’s nightmare, but a sea kayaker’s delight. You add the fog, which I hear is the dominant feature most of the year, and as a sailor you would have to stay so far off shore, you could be sailing anywhere.

But a small sea kayak or sea canoe like mine can go almost anywhere and experience the shore, and in bad weather take advantage of all those little passages and avoid rounding the big exposed points. I could not wait to get started. Getting into Portage Cove was only the beginning.

A Meeting at Sea

I had visualized and now immensely enjoyed going through Little Dover Run, then Dover Passage, behind Whale Island and many more islands to Eastern Passage. I would then pass White Island on my left, a huge chunk of almost white granite, to the mouth of Whitehead Harbor. There I had to gather my wits, take on some food and water and make sure I was set up right for the very exposed rounding of Flying Point. The wind had freshened to 15-20 knots out of the southwest with long older swells mixed in.

White granite on White Island

It was exciting, to say the least. The waves were thundering on the ledges and the steep shore. I managed to stay outside of all this mêlée, feeling awfully small and vulnerable all by myself, but kept on going, watching each wave as it approached and powering over it. Waves, that is all I think about in a situation like this, the next wave and the waves ahead, nothing else, no distraction, especially not about other people.

And then, almost half way into Port Felix Harbor, I saw about seven sea kayaks bobbing in the waves coming towards me. Who else is foolish enough to be out here in sea conditions like this, I thought to myself. It could only be a group led by Nova Scotia’s sea kayaking guru Scott Cunningham. So when we met up, I voiced my suspicion and asked them point blank which of them was Scott. They all pointed to a bearded fellow in the #2 boat. “Nice to meet you, Scott. I am Reinhard from Maine.”

And he recognized me also from my trip write-ups in Messing about in Boats and Atlantic Coastal Kayaker. We talked briefly. I learned they were headed for White Island and Canso, where I had been this morning. They looked at my sea canoe and were surprised to see me out here with that “broken kayak paddle”, my Zaveral bent-shaft racing canoe paddle, that is.

The rest of my boat passed inspection, since it looked like a regular sea kayak with rudder, and spray skirt held up with suspenders. Then I noticed I almost enjoyed answering their next question where I had put in and where I was headed, a bit too much: “Port Elgin, New Brunswick, headed for Halifax.” Most of them thought I was putting them on. Nobody does that but their trip leader, who did it with a friend and a dog in an open canoe in 1980.

But they calmed down a bit when they read the trip stickers on my boat, especially the one about my 1000 miles around the Gaspé. They were expert kayakers and knew what that meant. The whole meeting, only my third meeting with other people on my entire trip so far, did not take more than a few minutes. I pointed out the surf off Flying Point. They nodded, we parted, and each went his own way.

I still had a formidable task ahead of me, crossing huge Tor Bay by island hopping along the Sugar Harbor Islands with two miles of open water, straight into the wind at the end. Any open water crossing is a big deal for me, always. But I shifted into overdrive, and all went fine. I set up camp for the night inside of Berry Head. A day of great accomplishments, I wrote in my trip log, a stretch I had worried about before the trip. I had hoped I would rise to the occasion and meet the challenge, which I normally do, but I also knew one could never count on it.

Point Roundings

A large fog bank over the ocean and to the east greeted me the next morning, but visibility to the west was decent, and best of all, it was quite calm. I made good progress towards New, Coddles, Seal and Drum-Head Harbor where I briefly stopped for lunch. At that point the coastline was changing. For the next 25 miles, deep rivers and tidal estuaries were running into the ocean in a southeasterly direction, forming many pronounced headlands. After rounding County Harbor Head, Cape Mocodome and Barachois Head, my 25 miles were up again, and I found a lovely sand cove just inside the lighthouse of Port Bickerton.

The nicest moment of today’s paddle was hearing a herd of gray seals on Black Ledge singing their gurgly, throaty, howly growl and ignoring me completely. What a privilege to hear them; otherwise Nova Scotia has been surprisingly quiet. I heard only a few song birds, a few bald eagles and ospreys, but heard numerous ravens calling each other in their loud raucous voices.

Of course there were a variety of gulls, terns, cormorants, ducks, plovers and even loons, but it was basically quiet on shore except for the shrill whirr of the August cicadas. I saw no whales, porpoises or harbor seals, only loud, splashy, boisterous gray seals. It was quiet and lonely on the water as well as on shore. No truck, chain saw or people noises. From Cape Canso to New Harbor there isn’t even a road along shore, which translates into: there is no way in or out, for that matter, should you have a break down. You are on your own for sure.

Looking at my chart that evening I sincerely hoped for calm weather for tomorrow, because I had five more bad-looking points to round on my way to Liscomb Harbor. The first was called Fiddler’s Head, a steep drumlin island connected to a natural one-mile-long rock bar connected to another island-bar combination, making the whole thing extend three miles into the ocean.

If that was not bad enough, Fiddler’s Head was surrounded by more ledges in the two to three meter range, extending yet another 1.5 miles out, which in any sea would mean surf in all directions. Needless to say, I tiptoed through this minefield and into Indian Harbor, only to skirt another bar island 0.7 miles off Wine Head. The tide was low and there was no way of short cutting.

By then the wind had picked up to about 15 knots and was soon up to its usual 20 plus knots, and inevitably from the SW in these waters. I had to dig deep again to get anywhere. I rounded Cape St. Marys, then cautiously crossed the St. Marys River, not at its mouth, but a bit upriver, because it is one of Nova Scotia’s biggest rivers and I expected the ebb tide to do a job, but it was manageable. Again, there was no indication that there was a major harbor, Sherbrooke, upstream; it could have been an ocean bight, except for the flow.

Cape Gegogan was my next big problem. It had a 1.5 mile long bar running to a small island. The first half mile was already dry and to my initial horror had claimed a large freighter in its toothy fangs. It was the liberty ship The Fury, which had foundered here in a hurricane in 1965. It was already reduced to a huge skeletal hulk, but was still looming tall on top of a ragged ledge.

Shipwreck on Gegogan Ledge

Most of the sides had already corroded away; only the boilers and heavy engine were clearly visible. I snapped a few pictures, aiming the camera in the general direction of the wreck, since I could not let go of my paddle in the waves, or take my eyes off the waves for that matter.

Again I had to go into the next bay quite a distance before I dared to cross over. By now the wind was blowing 25-30 knots, and I was struggling around Redman Head to Gravel Head in outer Liscomb Harbor. I had expected some sand or at least gravel, but instead it was a very rough sea wall, which needed some landscaping before I could pitch my tent on it.

I investigated a small grassy area a bit further in, but was eaten alive by mosquitoes and opted for my windy rock pile. Liscomb Island used to be a homesteading island, I read, but today only a broken down pier and some level ground are reminders of those days.

Fog, Thunder and Rain - A Day of Rest at Liscomb

The weather report that night did not sound very promising: fog, rain, thunderstorm, winds gusting to 50 knots; high tide at 5:00, low at 11:00. Was I safe here? I was at least on the inside of an island and close to a real harbor.

Fog rolled in and the rains came down all night, but the 50-knot wind gusts did not materialize. I did not mind, but at sunrise the fog got so dense that I could not even see the end of the bar I was on, and since the coastline was changing yet again, a tangle of islands the likes of which I had never seen, I opted to sit out the fog and enjoy an extra cup of coffee and some reading.

Then suddenly at about 11:00 a.m. a violent thunderstorm hit. It was right overhead. The rain and wind were fierce (gusting to 45 knots), and the thunder got closer and more menacing. I quickly packed all my gear in my dry bags, spread a tarp over everything in my tent and steadied the tent from the inside. The storm went on for two hours, like a long band of thunderstorms. I was glad I was not on the water. I later talked with Scott Cunningham about this storm.

He confirmed my observations; he and his group had holed up in Canso Harbor.

By 2:00 p.m. the storm let up a bit, but the rain kept coming all day, while the fog wafted in and out. It was an enforced rest day, which I obeyed, sleeping away most of the day in my sleeping bag under an added rain tarp.

More Islands

The fog and rain were gone the next morning. It was clear again, I could see shore, but it was still windy (west 15-25). I was stiff from sleeping two nights on this rough sea wall, but the tide was in at six, making loading up a cinch. I was off, invigorated and eager to see this maze of islands.

Smith, Turner and Hayes Points were the three gateways to the Ecum Secum area. I had to paddle all the way into that little harbor just so that I could say that of course I had seen Ecum Secum and even Necum Teuch, which I did not even know how to pronounce then. (“Teuch” sounds like “Taw”, I just found out.)

After that I did more gunkholing, enjoying all those little passages and shortcuts only a sea kayak/canoe can squeeze through, and eventually ending up on the southern tip of Quoddy Head peninsula. It had a gravel beach facing west and east, so one could easily carry to the other side, should the wind shift. I worked hard to get to this place, almost seven and a half hours, but I felt I got going again after the forced day of rest.

The night was cold. The weather report was not kidding when it sent out a frost warning (for August 24!) and more wind from the westsouthwest, in the 20-25 knot range. Getting off at high tide was easy, but that also meant it would be ebbing for my 6-hour paddle today, and in these waters that would be to the northeast. Both wind and tidal current would be against me; no break again today.

It was still quite cold past Port Dufferin and Beaver Harbor into Sheet Harbor Passage. I stopped briefly to top off my water near the public landing, then scooted under a sturdy wooden bridge out into Sheet Harbor proper, which looks like the mouth of a big river, like Sherbrook just a few miles back. The wind was fierce as I clawed my way from Danbury Island via Western and Gibbs to Mushaboom Harbor and Bobs Bluff, where I finally found a protected little cove below the impressive granite bluff to enjoy an early lunch, since breakfast was only a cup of dry granola mix. No time for coffee or milk; I had to get around Taylors Head before the wind got even worse and the tide had run out.

Bob's Bluff near Taylor's Head

But I was too late for that, I realized, and slowed down with my lunch and rethought my predicament. Taylors Head is a very “conspicuous headland...a potential barrier to an extended trip”, Scott Cunningham points out. “Don’t round Taylors Head itself, except in very calm conditions.” Well, these were not calm conditions, but I figured it was not the wind, which made Taylors Head so dangerous, but the shallow 0.9 meter (3 feet) of water over the bar on its southwest tip.

This mile-long bar runs from the point itself to two tiny islands. At low tide, like right now, in any westerly wind, like the present westsouthwest 25, there would be surf for at least a mile to a mile and a half out to the red buoy (YA4). I wanted none of that under the present conditions and decided to hole up just east of the point in a small cove if possible, on the sea wall again, if necessary.

I felt a bit guilty about that since the entire point is part of Taylors Head Provincial Park, which does not allow camping. But I consider myself such an environmentally friendly minimalist, with a strictly adhered to carry-in/carry-out, no fires and leave-no-trace policy, that my moral compunction was also minimal. (Being a long time Maine Island Trail Association member, I know how to tread easy.)

My presence would most likely not even be noticed, I figured, since I always make a point of blending into the scenery in my granite colored tent, and boat which looks like bleached driftwood. For a safe point rounding, I argued against my offense, I needed an early start on the high tide before the wind springs up. And that is exactly as it happened the next morning.

Bay-Hopping

The day started with a wonderful sunrise illuminating a well-defined dark cloudbank in the northeast from below. Launching was again easy at high tide, and Taylors Head was very manageable, just a few old swells, breaking only occasionally. I felt good about my decision and felt energized to make up the miles lost yesterday. Today I would traverse a number of large harbor bays, all running northwest to southeast.

Sunrise over Taylor's Head

The first already came yesterday, Mushaboom Harbor, and today Spry, Popes, Tangier, Shoal and Ship Harbor as well as Owls Head Bay. Some of the Bays allowed an inside traverse like from Spry to Popes - I chose the pretty shortcut through The Baleens - and from Tangier into Shoal and from there into Ship and eventually into Owls Head Bay, a wonderfully protected and interesting inside passage through a myriad of more islands.

After Owls Head light I also took the shortcut behind Cuckold Island, only to find myself in a “field of ledges”. Sharp ridged long ledges everywhere; what a nightmare in the fog, even for kayakers, since there is no clear shore to hold on to visually.

Tidal Estuaries and Barrier Beaches

After Little Harbor, the shoreline suddenly changed yet again and continued like this all the way to Halifax. Suddenly there were very distinct and smooth shorelines with few ledges and ledge islands. The shore consisted of a string of large crescent beaches with occasional estuary or river outlets.

The chart revealed huge tidal basins storing up massive amounts of brackish seawater behind this barrier sand spit coastline, all running south, all leftovers from the last ice age. Most points along this shore were accentuated with drumlins, headlands of a glacial moraine, which were now slowly but surely crumbling into the sea, leaving shallow rock or gravel bars behind, while turning the rest into long swoopy sand beaches.

Clam Bay was just such a large crescent cove with drumlins, barrier beaches, tidal estuary outlets and all. It seemed endless, but then it also was my longest day, 31 miles (50 km) in 7:15 hours. With all those lovely beaches, I thought it would be easy to find a nice spot for the night. But the shore was shoaling too far into the sea, and many of the beaches were Provincial Parks or private. I ended up on a deserted sea wall again, somewhere before Jeddore Harbor.

Thick fog greeted me in the morning and hung around for most of the day. “I can handle that,” I thought to myself. “Along this type of shore, no problem, just watch out for the many ebbing tidal outlets.” I love navigating in the fog, figuring everything out ahead of time, then staring at the proper compass heading (don’t forget to compensate for the almost 20 degree westerly deviation, i.e. add it to the true course, don’t subtract it, or you’ll be in deep trouble!), checking my time and ignoring what my senses tell me, i.e. what I feel I should be doing.

Feelings and senses have no place in fog navigation, as in instrument flying. Plan prudently, trust your instruments, and do what you had planned to do. Do not double guess yourself or change your plan in midstream, is my advice; you are apt to get lost or run into trouble. My day went super, and I chuckled to myself as I checked off one point after the other.

The harbor and bay outlets of Jeddore, Musquodoboit, Petpeswick, Chezzetcook and Porters Lake were all ebbing, but not so hard as to create standing waves, more in the 1-2 knot range, for which one can compensate nicely. I loved seeing the line of drumlins peering through the fog between Chezzetcook Inlet and Three Fathom Harbor - great course markers.

At Wedge Island the fog lifted somewhat, which was nice, since this is a very formidable ledge point extending far out into the open ocean. I had originally thought of spending my last night of this trip on Wedge Island, but decided to go on when I got there. Should the wind breeze up in the morning out of the west, I figured I would have the darndest time making it to Halifax for sure at the pre-arranged pick-up time. Shut-In Island also seems to be connected to shore via a shallow rocky bar and would be impossible to cross in any westerly wind.

So I paddled on till I found a reliable spot for my last overnight, the eastern side of Half Island Point. Taking out was almost as hard as my first day, but I remembered to take out my water container. The rocks were slippery and impossible to walk on, but I do not drag my precious Kevlar boat, any boat for that matter. I am a sailor at heart, and that is one of the basic sailing rules I learned early: do not let your boat or any part thereof touch bottom.

As a result, I always seem to have the cleanest and smoothest bottom among boaters, boat bottom that is. My reward this time was a piece of level grass above the rocky low-tide shore, my first and only grassy spot of the entire trip. Great, I needed that.

Halifax Bound

My satellite phone was still on its first battery pack and worked flawlessly. Nancy had left Orono, Maine this morning and was already in Wolfville, NS. We would meet up at the boat ramp in Point Pleasant Park at the southern tip of Halifax proper, just south of the last harbor dock at 1:00 p.m. tomorrow. No problem here, only 17 miles! I did not tell her that the weather report had issued a small craft advisory again, 20-25 knot winds from the west, right in the face for me. I could do it, I thought to myself. Why worry her unnecessarily. (She most likely listened to the same report and is not telling me for the same reason.)

I was on my last chart of the trip, and I had studied up on Halifax, even set my VHF radio on channel #65A, should I need to get in touch with the Harbor Master to get a reading on the ship’s traffic in the main channel. I had to cross it from McNabs Island and knew it was a very busy place. Maybe I would leave the Harbor Master just a brief informational call saying a sea canoe was crossing over to Point Pleasant Park. You never know. Maybe fog would waft in. Then I would definitely need his help to cross over safely. For that scenario I had tied up my aluminum survival blanket in a large ball and had secured it under my spray skirt behind me, as a makeshift radar reflector.

All went fine straight into the wind, due west. Rounding Hartlen Point and the large ledge shelf surrounding it would be the hardest part of today. On the chart it looks as if Devils Island off its tip was once connected to the shore, leaving a shallow bar in The Gap, as this narrow channel is called.

Knowing this, I left a safe distance between me and shore and kept a healthy respect for the old swells breaking in The Gap. 20-25 knot wind waves are manageable, as long as the fetch is not too long, and I enjoyed the exciting last stretch of my trip. Then I slipped into more protected waters behind Lawlor and McNabs Island. The shore to my right was suddenly filled with houses, then harbor piers where big freighters were docking.

One large car carrier had just finished unloading a mess of VWs and Mercedes and was picking up steam as I was passing. Two tugboats made sure bow and stern would not run away. Then it motored up into the inner harbor, almost up to Georges Island, before turning sharp left past the main Halifax Harbor, down the reach to the open ocean. There were helicopters overhead, coast guard, fishing and pleasure boats, including lots of sailboats, criss-crossing the water in every direction, it seemed. And since visibility was great, I figured one more boat in this unorganized dance would be just fine.

It was only one mile across to my take-out. I checked for traffic, gauged the speed of other boats and mine and went for it. It was very windy, but I had my head down and wanted to get there. It was 12:30 p.m., and I had 30 minutes left.

And then suddenly I saw Nancy and our daughter Brenda on a ledge, waving exuberantly - what a nice welcome after such a lonely trip around an almost deserted and very desolate looking coastline.

Halifax Harbor

I had about 100 more yards to go when I was abruptly stopped by a Coast Guard boat with three officers on board. What now, I thought, as they came alongside, giving me the spiel about how dangerous solo boating was, about what a small craft advisory meant, etc. etc. Fortunately I was wearing my PFD with orange whistle, or else I would have been in real trouble.

But when they asked me what I was doing out here, where I had put in and where I was going, I had to smile and decided to make their day. “Port Elgin to Halifax, 450 miles in 19 days, solo.” I then showed them my compass, stop watch, air horn, VHF radio set on the Halifax Harbor Master’s channel (#65A), my home made radar reflector, pump and outrigger reentry pole with float-bag, and finally pointed to my satellite phone in its water-tight bag.

They were suddenly beaming, realizing that I was not the usual naive beginner “who should not be out there on a day like this”, but who, for a change, was immensely experienced, well prepared and equipped to be out on open water.

Arriving in Halifax

Instead of handing me a ticket or warning, they asked me whether it was OK to take a picture of me, with each of them in it, one by one. But I had the last laugh when I told them that they had interrupted my trip 100 yards short of my goal, with my wife and daughter dancing on the ledge ashore and waving their arms. I heard a big “woops” and a loud apology shouted over the water towards my family.

The End, for now

And that is how my 2003 trip around Nova Scotia ended. We stayed an extra day in town, since Halifax has so much to offer. I for my part just hung around the harbor, stepped on board the Bluenose, the sleek and incredibly fast former Grand Banks fishing schooner, and watched the replica of the 148’ square-rigger Jeanie Johnston arrive after its maiden voyage from Ireland, a big TV moment for the city. In the years 1848-1855 the original boat had made 16 voyages across the Atlantic, carrying 2500 Irish immigrants to these shores. I also did some people watching. I had met people only three times during my “19 days at sea” and was a bit people starved.

RZ and schooner Bluenose II

Irish square-rigger Jeanie Johnston

We then drove back to Maine via the Digby-St. John ferry, already talking about next year’s trip, which might take me from the same place in Halifax, along the South Shore of Nova Scotia and around Cape Sable to Yarmouth and Digby, another 375 miles. I’ll let you know.

Info:

Canadian Charts: Port Elgin to Halifax (for numbers, see Canadian chart catalogue)

Sailing Directions, Gulf of St. Lawrence. Fisheries and Oceans, Ottawa, Canada.

Sailing Directions, Nova Scotia (Atlantic Coast) and Bay of Fundy. Fisheries & Oceans.

Scott Cunningham: Sea Kayaking in Nova Scotia. Nimbus Publishing, Halifax, 1996.

Atlantic Geoscience Society: The Last Billion Years. A Geological History of the Maritime Provinces of Canada. Nimbus Publishing, Halifax, 2001.

Equipment:

17’2” Verlen Kruger Sea Wind sea canoe (Kevlar, with deck, spray skirt and rudder).

Carbon fiber bent-shaft canoe paddle (whitewater/expedition lay-up) by Zaveral, NY.

VHF marine radio telephone (with NOAA weather stations)

Iridium satellite telephone.

Sponsors: None

Reading:

Joseph E. Garland: Lone Voyager. Touchstone, 1963/2000.

Sebastian Junger: The Perfect Storm. Harper, 1997.

© Reinhard Zollitsch

BACK TO TOP OF PAGE