TRIP PLANNING FOR SUCCESS

By Reinhard Zollitsch

November 2007

General thoughts:

My motto has always been: Success is no accident, it is planned.

Saying, “I'd rather be lucky than good” does not work for me, especially on the water. “Lady Luck” is very fickle and extremely stingy, especially on this venue. And remember, if she does not show up on time, the consequences for you could be dire.

Sorry if I sound like a teacher (which I was) when I tell you that you would do much better in the long run putting some effort into practicing your skills, working out, getting in shape and informed, gaining experience and learning to stay cool in tight situations. My paddling many ocean miles confirmed that prudent planning and continuous vigilance are a much more reliable base to build on than hoping that "Lady Luck" will take care of you.

True, some people hate the word "planning" because they want to get away from their often overly structured life and be spontaneous. I agree with them. Sometimes it is fun to just drift around, let wind and tide take you wherever it will - but in my book only to a point: get real, you have to get back to land, or better your put-in spot where your car is parked.

I like to go with the flow also, but even that is planned and takes on a realistic meaning. On a rising tide and a SW wind I would rather paddle from Rockland, ME to Camden, for example, than the other way around, i.e. take advantage of tide and prevailing wind. When I am in my solo outrigger canoe, I prefer the wind to come over starboard and not port, where my ama is mounted. This allows me a much smoother, faster and much more stable and therefore safer and more enjoyable fun-ride than if I had gone in the other direction.

Getting out on the water around sunrise like the lobstermen do, also gives you a much calmer weather window, especially if you have to round exposed points or headlands. Unless you are in a storm system, it takes the wind a number of hours to strengthen, which it infallibly will along our shores in New England and the Maritimes. So I never leave shore unless I have listened to the latest NOAA weather report on either my VHF radio telephone or the Weather Channel on TV. If they predict a front or a thunderstorm to come through at, let's say, 2:00 p.m., you can be sure I am off the water and in my tent by then, even if that means getting up in the dark to get to my pre-set target for the day. So you see, I try hard to set myself up for success, not failure.

One more thing: whenever I push off, I almost always have a "Plan B" or even "Plan C" in mind, rather than doggedly adhering to my original "perfect" plan. Switching plans is then nothing more than a mid-course correction. It allows me to avoid the feeling of failure and lets me end up feeling accomplished after all.

It is also very easy, and often very depressing, to fall behind on a trip, to procrastinate and talk yourself out of doing what you had planned initially, more so in a group than being alone. As a matter of fact, I have hardly ever gone with a group (for me, two paddlers already constitute a group) that kept to its schedule. There were always excuses, breaks, stops and problems of one sort or another, or just plain disagreement as to when, where, how far and how fast to go. And that just does not sound like smooth sailing to me, and would really get me down.

But my greatest problem is going with paddlers who do not plan what they think they can do, but what they wish they could do – i.e. who set themselves up for possible failure right from the beginning, hoping that "Lady Luck" or the trip leader and the rest of the group will pull them through or out of the drink. Sea kayaking novices should not think of paddling around Monhegan Island, Maine (7 miles offshore) or doing the entire Maine Island Trail (~300 miles). They would surely be setting themselves up for possible disaster. And if by chance they happen to get away with it, this is no reason to swagger, but rather is setting a bad example for others and giving our boating fraternity a bad name.

I maintain that even going in a group, paddlers need to be self-reliant, and not depend on others for help and guidance. Competency builds confidence, which in turn leads to success. Other paddlers or the group are only there in case of a dire emergency. From my point of view, hard as this may sound, other people are mostly more of a liability than actual help.

Even in the tightest situations, I am always glad I am paddling solo and do not have to worry about my partner making a mistake - I have set myself up NOT to make one, and do not want my concentration to wander for a second, and it would, because I care about others. This brief lapse in concentration might then in turn even get me into trouble. (But don't get me wrong. I am not saying you should all go solo. That takes a lot of guts, skill, experience and mental fortitude.)

Prudent preparation, including an accurate weather report and careful map reading, a sound boat and equipment, practiced skills and a sharply focused and aggressive mind have always carried me through tight situations. So how do you get ready to paddle alone (or in a group) with success - getting out of your boat offshore and being rescued by someone else, may be nice, but does not count as success in my book.

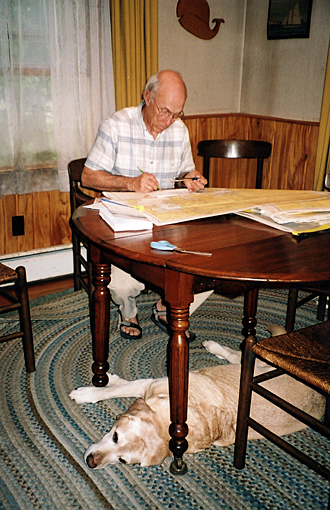

Ready to go 350 miles down the St. Lawrence, May 2007

A - you, the paddler:

Make sure you are mentally, physically and technically up to the trip planned and in the best possible shape. Be positive and ready and know what lies ahead. No drifty “I hope...We'll see when we get there...” Set reasonable goals and know your limits, and prudently bail out when you have reached them.

B - your boat and gear:

Have the right boat for the trip you plan. Paddling the entire Maine Island Trail solo in an open C-1 whitewater racing canoe, as I did in 1996, does not sound like a good choice in retrospect. It was exciting and a challenge, though, but please do not imitate that. You see, that was the only boat I had other than downriver racing kayaks, and I was just starting to canoe on the ocean. But I had made significant alterations to the boat, like adding a rudder, a 3-foot bow deck, hip braces on the seat, extra flotation and retainer ropes, which made sure my water-tight bags would not float away if the unthinkable happened, and I had gone on several long (up to 100 miles) practice runs.

The following year, though, I switched to a covered Verlen Kruger Sea Wind sea canoe, with rudder, spray skirt, Ritchie compass, lensatic radar reflector and bicycle wiggle stick. I have a VHF radio telephone, a satellite phone, an air horn, bailer and pump, you name it, I am ready and totally self-contained for trips up to 3 weeks - all food for the entire trip plus 5 gallons of water safely stowed below decks. I hate to stop in harbors for munchies, drinks, food, campgrounds or motels.

C - trip info and the mind:

Success for me goes beyond being safe and getting where I wanted to go and on schedule. You also have to be mentally happy doing it, have to have something to think about and figure out - keep your mind occupied and not get bored paddling 25 miles or 6-8 hours every day. I always seek out all the pertinent info about the area I paddle, including history and geology, and above all get real paper NOAA charts for ocean trips, as well as the Coast Pilot and tide tables, and geodetic survey maps for river trips.

Having those, it is much easier to plan your overnight spots ahead of time. And again, know your own physical capabilities, i.e. choose 15/20/25 miles per day on average, or whatever you can comfortably do. For me, nothing is more comforting than knowing where I will stop for the night. Saying “I am sure I'll find a good place when I get there", is fraught with trouble – you may be miles off shore at low tide on the St. Lawrence or in Fundy Bay when your tank runs empty - PORTAGE! Or worse, there is no place to land for miles because of the steep, rocky shoreline, as around the Gaspé in Québec, or Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia.

D - Safety:

A successful trip, first and foremost, is a safe trip - which takes a lot of preparation (see above). But you also need a contact person to report to on a daily basis. Don't count on a cell phone to work, and remember, your VHF has a range of only 20-30 miles, even in an emergency! So the Coast Guard can be out of reach, and is most of the time, in those areas where I paddle, anyway. I call home every day at 5:00 p.m. via my satellite phone, a brief 3-minute call. (It is amazing how much you can say when you get organized ahead of time. At $1.40 per minute, there is little time for chit chat.)

These days, EPIRBs launch a major rescue effort, and are only for bigger ships, I was recently told. Sea kayakers should use a PLB (personal locater beacon) which would trigger the proper response, but both are still exorbitantly expensive. So if you do not have the moola, and few of us do, it is always a good idea to check in with local area Coast Guard, maybe even file your float plan with them via e-mail ahead of time. I have also found it very useful to tell the first fishing boat you meet, where you are going. They will pass on the word from boat to boat along the shore you are traveling, as a news item. This happened to me around Prince Edward Island and along the shores of New Brunswick and Nova Scotia, and was a very comforting, yet unintrusive feeling.

E - the comfort factor:

Trip planning for success also addresses the comfort factor - bodily comforts, that is, like the right clothes (polypropylene, polar fleece, nylon, Gore-Tex, wet-suit, dry-suit, booties and gloves; but no cotton or wool; "cotton kills", since it accelerates hypothermia, and wet wool never dries.) You should also have camping gear with no-see-um screening including a headnet, and a reliable campstove with new, i.e. full propane tank (avoid liquid fuels - they always spill or leak). And don't leave home without sunscreen, Tylenol, your medications as well an emergency First Aid kit. A urinal for in-boat use and buggy nights in the tent is also a very comforting thing to have along.

And don't forget to work on your mental health: Stay focused and eager, think positive thoughts and avoid exhaustion, frustration and depression. Do not try to solve family or work problems on the water - you'll dump for sure. Instead take some interesting mindless fun-readers along, and write a trip log to put everything in perspective and help you remember things after the trip is over. Blogging while on a trip, with a solar panel recharging system, seems to be the cool way to go these days, but is fraught with trouble. It definitely goes beyond my minimalistic approach.

Whatever you pack, think "portage", even if that is only a couple hundred yards to shore at ebb tide to your overnight spot above high-tide mark. You will leave many non-essential items at home. Streamline your gear until it will all fit below decks. Nothing should be tied on deck other than your chart, compass, stopwatch, spare paddle and wet-reentry pole with float bag. And please, do the test packing at home, not at the put-in place with everybody watching and waiting. All too often I see tripping sea kayaks with big bundles tied to their fore and aft decks. How do those paddlers think they are going to do an emergency eskimo roll? They are headed for big trouble, as I see it.

Final thoughts

That about does it, my friends. So if you are thinking about taking a trip on the ocean, try not to become one of those all too often shown or written-about near- disaster boaters. But if that does happen, please do not swagger about your own near-disaster moments in print. For all it reveals is poor planning and judgment, and is nothing to be proud of. Even pedagogically, negative examples and failure are not nearly as edifying and confidence building as positive success stories, which include a subtle hint as to what went into the success. Learning from others' mistakes and doing it right, is always better and less painful than making those mistakes yourself and hoping to be given a second chance to learn from them. Remember that fickle, stingy "Lady Luck".

Careful, yet flexible, trip planning is thus not a sign of a stiff, regimented, non-spontaneous mind, but rather the sign of a person enjoying success in a harsh, unrelenting environment that will punish you for not paying attention and showing respect. Think about that.

Take care, be safe, and have fun.

-Reinhard

PS: For Reinhard's trip reports (canoeing 4,000 miles solo around all New England states and Canadian maritime provinces), as well as other related articles, see his website at:

www.ZollitschCanoeAdventures.com

e-mail: reinhard@maine.edu

© Reinhard Zollitsch

BACK TO TOP OF PAGE